*

With 2019 quickly fading, social media was plagued with personal then-and-now posts. On Twitter, side-by-side personal photos—one from 2009, the other 2019—projected glow-ups and always-gentle refinement. On Instagram, captions about how quickly the decade has escaped us sat beneath carefully curated portraits of a user’s best angles throughout the 2010s. On Facebook—well, wait. It’s 2019. Who uses Facebook anymore?

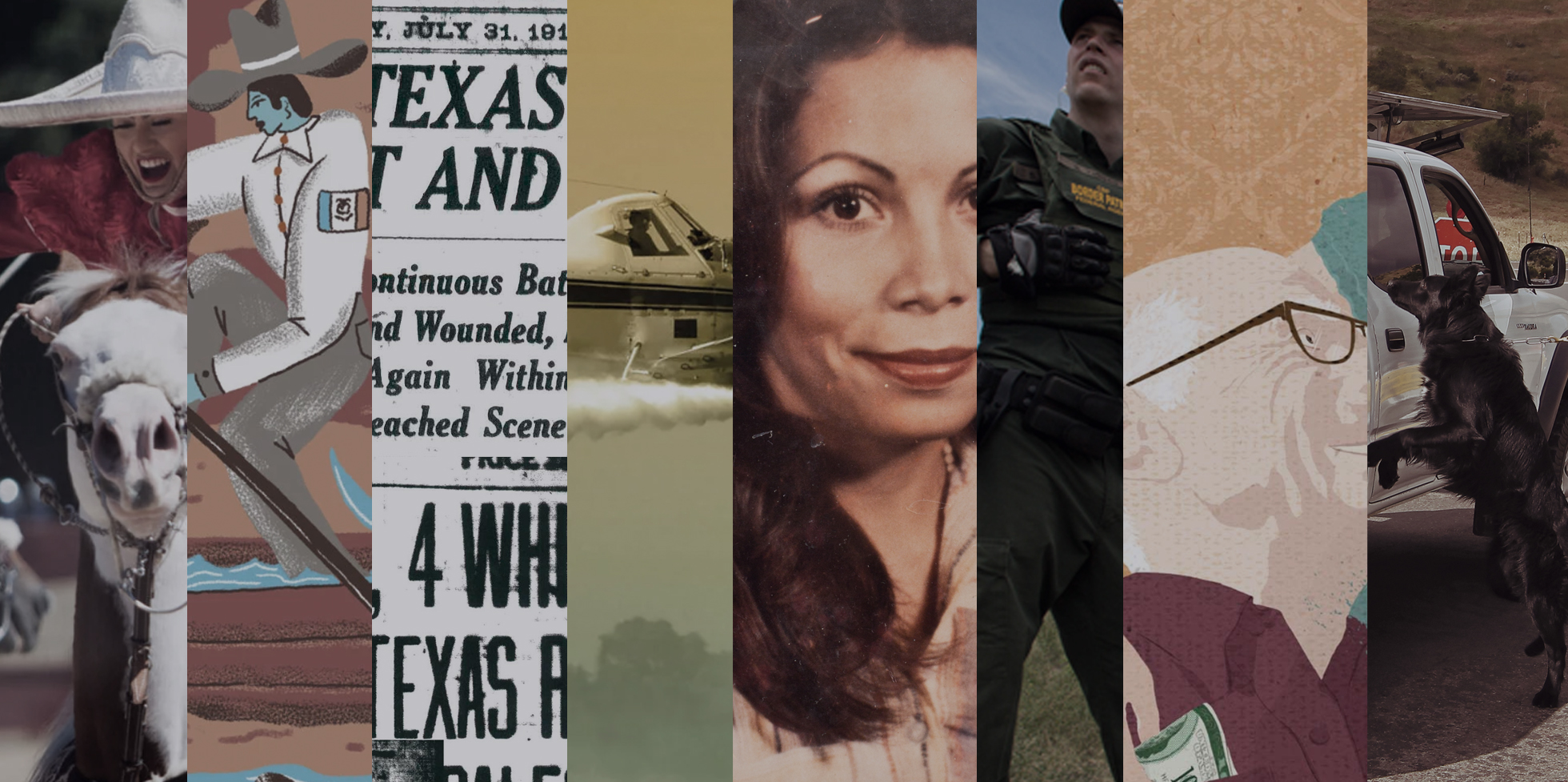

Here at the Texas Observer, we’re thinking about the past decade, too, but we’re not going to mark it with a selfie. We decided to kiss it off the way we know best: with some ass-kickin’ journalism. We reached out to Observer editors and writers, past and present, to ask them which of our stories from the 2010s have stuck with them—the ones that affected change, won awards, shifted their view of the world. It was a tough task, to be sure, but our informal nominating committee came up with a capsule of our decade of tireless work.

A lot has changed in 10 years. Hell, a lot has changed this year. But we know this: then-and-now, the Texas Observer will hew hard to the truth. —Abby Johnston, executive editor

Halfway through her pregnancy, Carolyn Jones learned that her baby was ill. A molecular flaw had determined that her son’s brain, spine, and legs wouldn’t develop correctly. If he were to make it to term—which wasn’t guaranteed—he’d need a lifetime of medical care. Together with her husband, Jones decided to terminate her pregnancy. But thanks to a Texas law that had just gone into effect in 2012, the painful decision was only the beginning of her torment. For Jones, the politics of the abortion debate suddenly became very personal.

On June 2, 2011, a man broke into Indira Paz’s house in southeast Houston, bound her with zip ties, and raped her in front of her 4-year-old daughter. Paz never got to testify against her attacker, because he was never caught. But nearly eight months later, she was asked to testify about the behavior of Houston police officer Alan Sweatt, who responded to the call that day. This story is the first in a two-part investigation into the lack of accountability within the Houston Police Department.

In 2012, 271 migrants died while crossing through Texas, surpassing Arizona as the nation’s most dangerous entry point. The majority of those deaths didn’t occur at the Texas-Mexico border but in rural Brooks County, 70 miles north of the Rio Grande, where the U.S. Border Patrol has a checkpoint. To circumvent the checkpoint, migrants must leave the highway and hike through the rugged ranchlands. Hundreds die each year on the trek, most from heat stroke. This four-part series looks at the lives impacted by the humanitarian crisis.

Though abortion itself is now extraordinarily safe, it’s also become, if anything, harder to get than it was in the 1970s—especially in Texas. That makes the story of Rosie Jimenez, a young woman in McAllen who died of an illegal abortion in 1978—four years after the procedure was legalized in the United States—more relevant than ever.

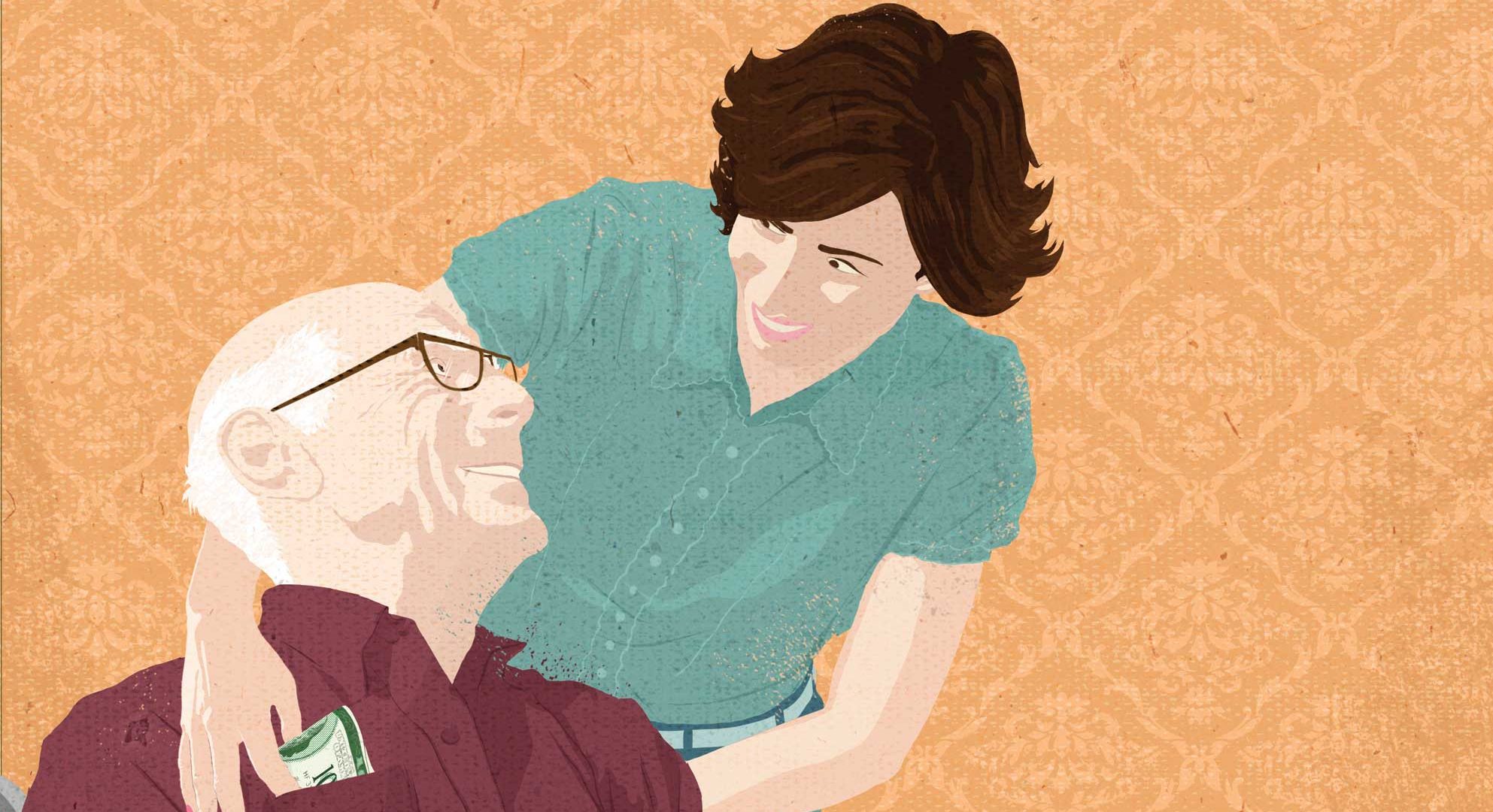

Guardianship is the state’s last-ditch tool to protect people from neglect or abuse, and although it saves lives, it can be a blunt instrument. More than 53,000 Texans, most of them elderly or intellectually disabled, were under guardianship when this story was written. Some could never make their own decisions; others, in the eyes of a friend or family member, have been making decisions that are dangerously wrong. In either case, the remedy is the same: Their legal rights transfer to a person of the court’s choosing. Texas counties have stripped thousands of elderly and disabled citizens of their rights—and then forgotten about them.

People in Texas farm country say they are under assault from crop dusters indiscriminately spraying chemicals. Our investigation found that from 2013 to 2016, TDA received about 900 reports of pesticide drift statewide, and of those, 169 were cases in which people said they were involuntarily exposed to dangerous chemicals. Complainants reported asthma attacks, bleeding gums, headaches, burning rashes, vomiting and diarrhea. And serial offenders, we found, were often allowed to keep flying.

“Eventually, there will be a group of young women who get together and try something new. So yes, I think we’ll see an all-women’s charreada someday.” Within charrería, traditional Mexican rodeo, there is only one women’s event: escaramuza. The sport is sometimes described as ballet on horseback, though that analogy doesn’t fully capture its danger and speed. Within the macho world of charrería, women riders are taking the reins.

The Rio Grande Valley of Texas is one of the fastest-growing places in the United States. Already hot and arid, and growing hotter, the booming, heavily Latino region depends almost entirely on the shriveling Rio Grande, which is considered one of the most endangered rivers in North America. As the river continues to shrink, 6 million people and 2 million acres of farmland on both sides of the Texas-Mexico border rely on it for drinking and irrigation water. This nine-part collaboration between the Texas Observer and Quartz explores the complexities of border water in a hotter, drier world.

Some 200 million people—nearly two-thirds of all Americans—live within the “border zone.” Immigration authorities are extending their reach deep into the interior, putting civil liberties in jeopardy for millions of people. This collaboration with Harper’s Magazine, the first in that publication’s 170-year history, digs into the 100-mile zone along any U.S. border where constitutional rights are routinely trampled in the name of national security.

The 1910 massacre in Slocum—one of America’s deadliest post-Reconstruction racial purges—shocked people from Abilene to New York, who read about the killings in newspaper coverage in the days that followed the spasm of violence. Authorities called the episode an embarrassing stain on the state and region and vowed justice. The outrage was short-lived. One survivor’s descendants have waged an uphill battle for generations to unearth that violent past.

A special thanks to former Observer editors and writers Dave Mann, Patrick Michels, Naveena Sadasivam, and Forrest Wilder for their submissions.