Ever since Jurassic Park fascinated us with the first image of a gentle brachiosaurus roaming on a grassy plain, audiences have been waiting decades for another cinematic spectacle revealing new insights into dinosaurs and the prehistoric world.

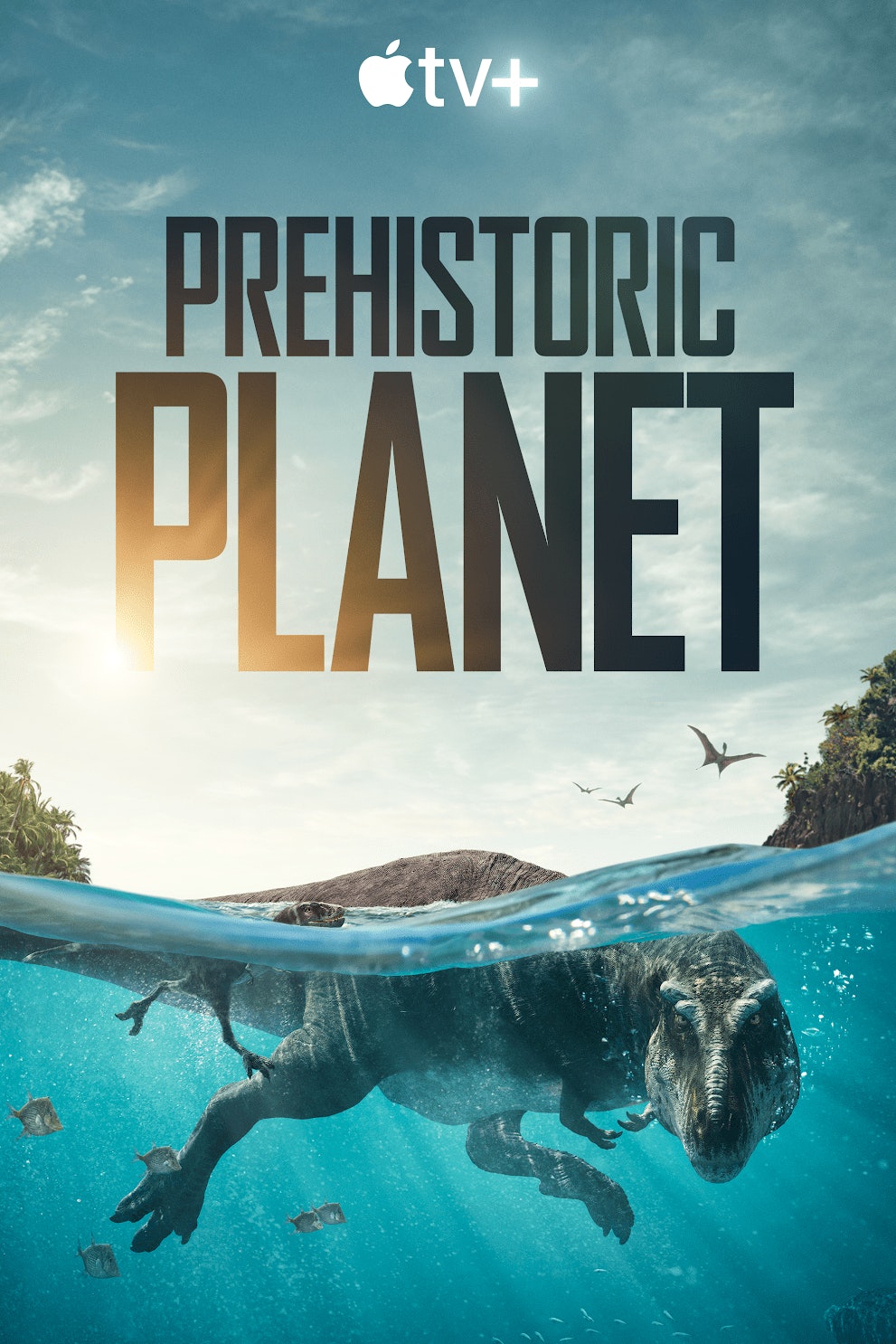

Now, the wait is finally over with the debut of Apple TV+’s visually stunning new series, Prehistoric Planet. Narrated by none other than natural historian Sir David Attenborough, Prehistoric Planet is a five-episode limited series that began airing on Friday, May 27.

While Jurassic Park imagines what would happen if we brought dinosaurs to our modern world, Prehistoric Planet does something arguably even more daring: it uses real science and computer animation to recreate the very world in which dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex lived, feasted, and played alongside other majestic creatures in environments ranging from harsh icy worlds to coastal tropical climates.

But just how did the show’s creators use science to accurately recreate the daily life of animals we’ve never seen in real life? Inverse sat down with series showrunner, Tim Walker, and chief scientific consultant and palaeozoologist, Darren Naish, to explain the unbelievable science behind the breathtaking series.

Reel Science is an Inverse series that reveals the real (and fake) science behind your favorite movies and TV.

How did Prehistoric Planet recreate the past?

Walker’s focus was getting the science right from the moment he began assembling the creative team behind the series, including Naish. Their goal: to recreate the era before the Cretaceous–Paleogene mass extinction event that killed off the dinosaurs and most of life on Earth, or what Walker calls the “last great period of the dinosaur’s evolution”

“It was science embedded right from the start,” Naish says.

But recreating the ancient past circa 66 million years ago is no easy feat, especially for a series 10 years in the making. So how did they do it? As it turns out, we already have a pretty great fossil record from this period, owing to decades of archaeological research.

“It also features a couple of big hitters within the Dinosaur World,” Walker says. “T-Rex and Triceratops, they were only around in that short window of time.”

With a strong crew of wildlife filmmakers from BBC’s Natural History Unit and a CGI team led by Jon Favreau (The Mandalorian), Walker brought Naish onboard to verify the real-life scientific details of how animals lived during this time. Naish’s interpretation of bringing the fossil record to life through comparative biology and other disciplines was critical to translating old bones into real, breathing creatures onscreen with accurate muscle movements.

“We’re in a dinosaur revolution.”

But Naish admits there were two key challenges going into the series.

“Number one is we’re in a dinosaur revolution. More new species are being described than any other point in history,” Naish says.

More information might be good for creating a realistic series, but it also means greater critical scrutiny from a well-informed audience, who will be keen to make sure the details in the series line up with the latest scientific research concerning the appearance of dinosaurs and other creatures.

The second challenge was deciding which animal behaviors to feature onscreen and which were up-to-date with the most exciting new discoveries.

“I really think we've pulled it off,” Naish says.

How did Prehistoric Planet bring ancient animals to life?

Prehistoric Planet features both familiar faces like the well-known T-rex as well as new ones, like the tyrannosaur Qianzhousaurus — a dinosaur from eastern China known as “Pinocchio rex” for its long snout — that have never been seen on screen. Other animals, like the mosasaurs — a monstrous aquatic reptile twice the size of T-rex — also make an appearance.

So, how did Naish and Walker pull off recreating the appearance and behaviors of these creatures down to the most minute detail? For some animals, we know pretty well what they looked at during various stages of life based on complete fossils. But for other creatures, the fossil record may not yield all the information needed. Therefore you need to draw comparative references based on the behavior of living relatives of these extinct species — a technique known as bracketing.

In the first episode of the series, we’re taken to the coasts and oceans of the world. One sequence at the end of “Coasts” features a live birth of a ten-foot-long baby plesiosaur (a large marine reptile).

“That’s based on a specific fossil, where a mother plesiosaur has a baby preserved inside her,” Naish says, “so we know that those animals gave birth to a lot of so-called live births.”

In another moment in the episode, a plesiosaur swallows large pebbles to provide stability while they’re swimming — a fact that is well-known in paleobiology. But there are other times when Naish had to go beyond what was strictly in the fossil record. In one fun scene from “Coasts,” a mosasaur visits a “cleaning station” where a group of fish essentially clean the mosasaur’s body of old skin, which they then consume as food.

There’s no hard scientific proof that mosasaurs engaged in this behavior, but scientists think it’s likely based on the behavior of real-life marine mammals like sea turtles.

“Our stories represent this very complicated marriage amalgamation of data or information with the fossil record with this knowledge of what's seen in the living world, often using this bracketing technique where you're looking at the living animals that surround the extinct one,” Naish says.

Walker adds that by observing the behavior of modern animals in specific environments, they were able to make educated guesses about how dinosaurs and other extinct animals might have lived.

“The same kind of challenges apply 66 million years ago as they do now,” he says.

How did Prehistoric Planet find new ways to show dinosaurs?

“Our great desire is to show dinosaurs in a different light,” Walker says.

One of the show’s most fascinating revelations lies in the opening moments of “Coasts,” when an adult male T-rex takes its baby for a swim to a nearby island. But the sea voyage is filled with peril. A mosasaur can easily kill a baby T-rex, so the series shows how father and offspring navigate this potentially deadly voyage while fending off the larger.

For audiences familiar with T-rex, this sequence will come as a surprise for two reasons. For one thing: the fact that T-rex can swim given its small arms. Most on-screen depictions of T-rex show the creature running on land with its small arms at its sides. Yet, these massive dinosaurs probably could swim quite well due to their powerful hind legs, massive splayed feet, and a spinal column filled with air, which allowed the animal to sit higher in the water.

“Does it look like T Rex was a good swimmer? Yes, it does. It's got loads of anatomical features that show you this animal was very competent in the water,” Naish says.

From the fossil record, we know T-rex lived in some swamps and coastal areas. Like lions and wolves — prior to the arrival of humans — T-rex wasn’t restricted to a specific environment, but instead lived in a pretty long strip of western North America.

So while T-rex may not have swum every day, it probably would have crossed bodies of water in search of food. Direct fossil evidence known as “swim trace marks,” which refers to marks on the bottom of a river bed or seafloor, further confirms the T-rex could swim.

“What we want to show is the dinosaurs were monsters. They were majestic and magnificent and they were part of the ecosystem,” Walker says.

The second reason this swimming sequence will surprise viewers? It portrays T-rex not simply as an apex predator — or a murderous beast a la Jurassic Park — but as surprisingly vulnerable and majestic creatures, especially as young babies.

“In terms of filmmaking, the natural world is filled with babies, they play a key role and they're very enticing,” Walker says.

Naish adds, “Most dinosaurs were babies and youngsters, and big adults were comparatively rare.”

Like any other animal, T-rexes had to take on parenting duties. From the fossil record, we know dinosaurs had many offspring compared to other kinds of animals. The more babies, the greater the likelihood that you will lose a few before they reach maturity — this is true across the animal kingdom.

“You know, people might not like it, but the deaths of youngsters would have been very common,” Naish says.

But while many viewers will likely flock to the show because of T-rex, Prehistoric Planet’s science is arguably at its best when it goes beyond dinosaurs, showing us the complex ecology of prehistoric life in ways that are new and dazzling to viewers. One of the first episode’s most breathtaking sequences features not a dinosaur, but a glowing ammonite that lights up the sea.

“This series is called Prehistoric Planet,” Walker says. “It's not called Dinosaur. And so we wanted to show the planet and its inhabitants.”

Prehistoric Planet is streaming now on Apple TV+.