Arguably the world’s biggest and greatest rock band, The Rolling Stones continue to swagger across the world's biggest stages, more than 60 years after their inception.

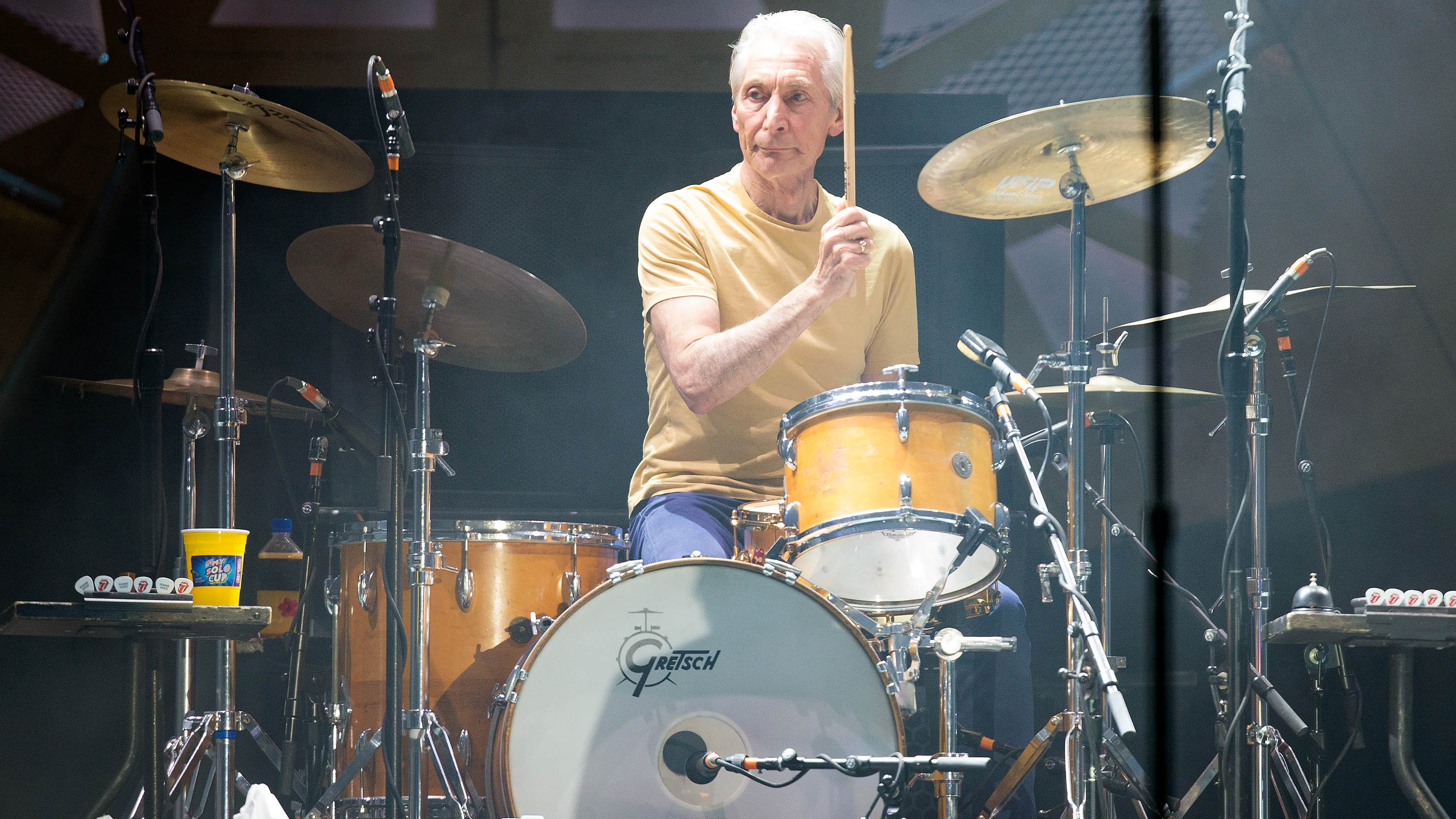

Behind the Jagger swagger and the unquestioned status of Keef as guitar god, many considered drummer Charlie Watts, who sadly passed away aged 80 in 2021, to be the coolest member of the band. And with good reason.

Understated but impeccably laying down the grooves behind the r’n’b influenced rock tunes, Charlie’s swing was what made the Stones so essential and influential. Yet many fans who have enjoyed his key contribution to Stones classics like ‘Paint It Black’, ‘Gimme Shelter’, ‘Tumbling Dice’, ‘Honky Tonk Woman’ and ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ might not be aware that Watts is a schooled jazzer, whose boyhood hero was Charlie Parker. To the end, Watts continued to indulge his passion for jazz with the Charlie Watts Quintet and Tentet and put out a number of recordings paying tribute to Bird, as well as covering jazz and swing classics.

Growing up in Wembley, London, Charlie discovered drums through the playing of Chico Hamilton, and it wasn’t long before he was playing first in a swing band and then with British blues pioneer Alexis Korner, whose Blues Incorporated were regulars at the G Club in Ealing. The G Club was patronised by Mick, Keith and Brian Jones, who inducted Charlie into their band, even as he continued his labours as a commercial artist.

Here we present a classic interview from our archive, in which the coolest Stone discusses his early years with the band, his enduring love of jazz and the players who inspired him.

You continued with the day job even once you’d joined the Stones. Did you enjoy your work?

“Yes. I’m very easy like that. I was a designer, mostly advertising. I did three years as a lettering artist. I went from there to a design studio, an agency. I was doing it all the time I was with Alexis, and I was doing it when I was with The Stones, but I was ‘between engagements’ when I officially joined the Stones.

We had the best frontman in Mick, and Keith was such a good rhythm guitar player, which is what he used to play in those days

"I’d played with them before, but I was asked to come along to rehearsals by Brian [Jones] I used to hang out with them, go to job interviews, come back and we’d play the 100 Club. I’d get up in the morning and Brian and Keith would be snoring away, and I’d think, ‘I’m not going to an interview today – we’re playing tonight anyway.

“We had a lot of work in London and Richmond, four or five nights a week. We didn’t actually go around England in the early days. It’s terribly glamorous being on the stage, and suddenly I was in a band where everybody was clapping. Alexis was a big band to be in, but The Stones had such a mad following and it got bigger every week.

"And then The Beatles happened, and it became the thing to be in a beat group. And it was a great spawning ground for some strange players, some good. The Animals were a very good band live. The Stones were the best though, I think.”

What made you the best?

“Dunno. I think we swung, a lot. The Animals used to swing as well. They used to do a great version of ‘Almost Grown’. What made us the best? Being my band [laughs]. We had the best frontman in Mick, and he was, even in those days. And Keith was such a good rhythm guitar player, which is what he used to play in those days.

"He used to lead in but it was mostly rhythm. And Brian was good at what he did, so it was a great sound to have in the band. He’s like Ronnie [Wood], who’s a great guy to do anything. Ronnie’s a great adapter.”

Did you ever feel any regret that you came from this jazz background and suddenly you were playing rhythm and blues?

“No. I got introduced to this music. I was never a rock’n’roll fan when I was a kid. I used to love Fats Domino and Little Richard, but I was never an Elvis fan, I never followed the charts, and I liked Duke Ellington and Bird. I never had any trouble listening to jazz; it’s very easy for me.

I never followed the charts, and I liked Duke Ellington and Bird. I never had any trouble listening to jazz; it’s very easy for me

"Some of it I think, ‘Oh God, I wish this would end,’ but not all jazz or improvised music is good. Most of it is just trying to be good. But when it does peak, it’s of a standard that is unbelievably high.

“But I got into this world with Alexis and The Stones. I’d never heard of Muddy Waters, and Keith and Brian used to play endless Chuck Berry and Jimmy Reed. And Jimmy Reed’s Earl Phillips is one of the great jazz drummers in a way.

"He’s got such a quirky way of playing, and Chicago shuffles are technically very difficult to do. And when you see them do it properly, the old guys, it’s fantastic, because they come down on the backbeat so loud. They get this shuffle-like thing in between – it’s fantastic – without the feet going. And usually they play very quiet, the old guys. So to me it was not really any different, to be honest.

“I was young and we were off, playing around England with The Everly Brothers, who then had a fabulous drummer. He was young, 19 at the time. He’s on ‘Layla’ – he wrote ‘Layla’ with Eric. Jim Gordon, he was a fantastic player. We’d never seen a band as slick as that. That tour we had Bo Diddley.

"I think Little Richard was on it, a fantastic crowd of people to be stuck up in Leeds with, that lot. Jerome Green was the most incredible maraca player, and Mick learnt how to play the maracas properly, he can play waltz time and all that. The hard thing is stopping them, and he learnt that from Jerome.”

Did you feel competition with the other drummers around at the time?

“No. Yeah… well, you’re young, you know, so you get that. But I always gave up. Alexis’ band got so bloody big and good, with Jack Bruce and Graham Bond, that I just stepped out of it and let in Ginger, who at the time was probably the best player around. He still plays great, Ginger. He’s the nearest thing to an African we’ve got. But you used to see a lot of guys playing – Bobby Elliott is a really good player. Originally, I think, they had another guy, who played with them when we first went up the M1 and played away from home. The Stones, that is – I’d been up there once with Alexis.”

What was it like when you went into a recording studio for the very first time? When you heard yourself playing on record were pleased or was it a somewhat weird experience for you?

“I was thrilled. Glyn Johns took us in there, we did eight tracks in about 10 minutes and went off and played a club. I was sitting in the same booth where Phil Seamen used to do jingles, so I was happy to pretend I was there. It was IBC, opposite the BBC. Glyn did it when they stopped work at 5.30; he had some spare time. I personally have been very lucky with engineers, because they’ve all been good with drum sounds. Then when we did ‘Satisfaction’ in LA, the RCA guy was great as well. I can see him now with his Tinterello cigar.”

It all seems like such an incredibly exciting time, some of the musical changes you saw between 1960 and 1970…

“I think now that you’re not given time to learn what you do. One of the greatest things about jazz drummers is that you have to learn to play with a piano player acoustically, with a saxophone, a trumpet, at those volumes without losing intensity.

I love playing, I always wish I was better

"And to watch an artist like Art Blakey do it was incredible, because he would go from deafening noise to one of his tricks, this press roll he’d do on the cymbal, and then he’d come down and your breathing would be louder than his playing, but there’d be no let up in the intensity. So there isn’t this, and there isn’t the playing going on.

"Now the whole thing is set out. The kid learns to dance, do a video… the backing track’s already done. I like loops and all that and I like rap rhythms. It’s great to hear, but it’s such a produced thing. If you’re learning to play you never play a bass drum like they do on a rap record, because the tracks are altered, the sounds are altered.”

You seem to be as passionate about music now as you were at the beginning.

“I love playing, I always wish I was better. One of the faults of listening to great players is that you know you could never be that. I knew that when I was 20 I could never accomplish that. I’m not rounded enough or dedicated enough. But I’ve never lost the passion of wanting to play the drums.”