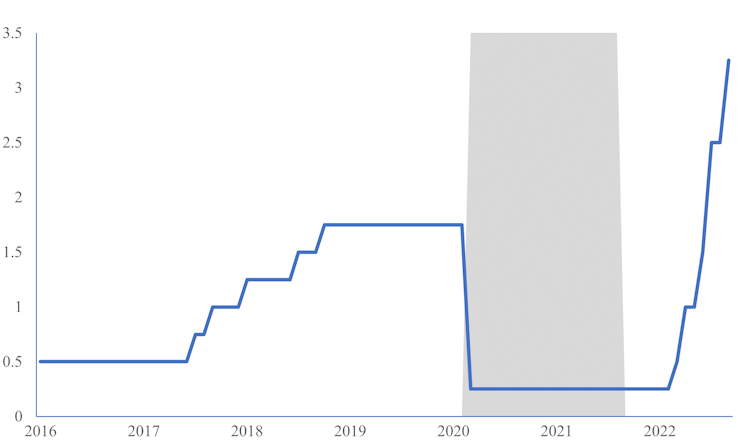

The Bank of Canada has raised interest rates again in an effort to quell inflation. The central bank raised its policy rate by 0.75 percentage points on Sept. 7, bringing its benchmark overnight rate to 3.25 per cent. Economists are expecting the central bank to raise it again before the end of the year.

By now, it’s clear that the Bank of Canada did not anticipate the current rate of inflation. When inflation first started increasing last year, the central bank was slow to start tightening monetary policy. Now that inflation is persistent, the Bank of Canada is making up for lost time by aggressively raising its policy rate to get the inflation rate back on target.

Monetary policy has a delayed impact on the economy, meaning that a change in monetary policy today will affect the economy about 12 to 18 months from now.

Although supply chain problems, high energy prices from the war in Ukraine and labour shortages have exacerbated inflation, the unprecedented expansionary monetary policy by the Bank of Canada last year is an important source of the high inflation we observe today.

Getting back on track

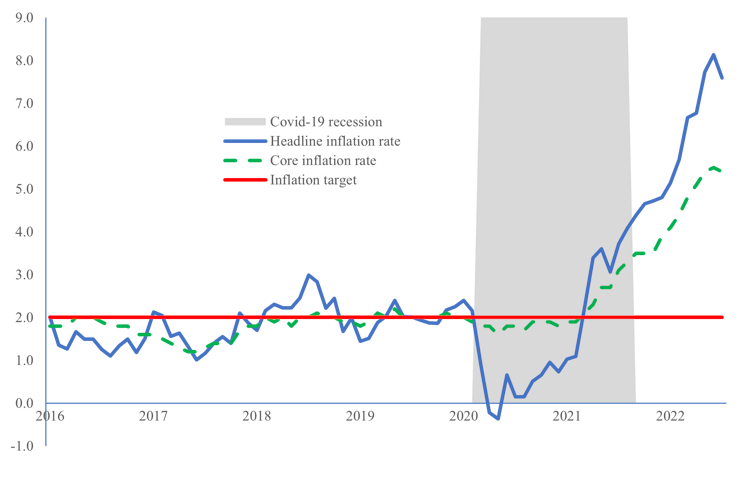

The goal of Canada’s monetary policy, jointly determined by the Government of Canada and the Bank of Canada, is to keep the inflation rate within a range of one to three per cent, with two per cent being the most desirable rate.

In early 2021, all key inflation indicators started to rise dramatically, and as of now, are all well above the two per cent inflation target.

The total consumer price index inflation rate was 8.1 per cent in June 2022 and fell to 7.6 per cent in July 2022, mostly because of a decline in gasoline prices. The core consumer price index inflation was also well above five per cent in July.

Read more: An economist explains: What you need to know about inflation

Inflation also rose in the United States, Europe and the United Kingdom, with annual inflation in these countries now running at around 9 per cent and central banks flagrantly missing their inflation targets.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, the Bank of Canada rapidly lowered the policy rate to near zero and kept it there until early 2022. Since then, the Bank has been steadily increasing the policy rate until the most recent hike.

According to the central bank, it could be years before its policy rate is back to normal levels. Currently, the Bank of Canada estimates that inflation will decrease to about three per cent by the end of 2023 and return to the two per cent target by the end of 2024.

But this remains to be seen. In this regard, back in 2020 the Bank was expecting the policy rate to remain at 0.25 per cent until 2023, but is now at 3.25 per cent and rising.

Bank of Canada assets

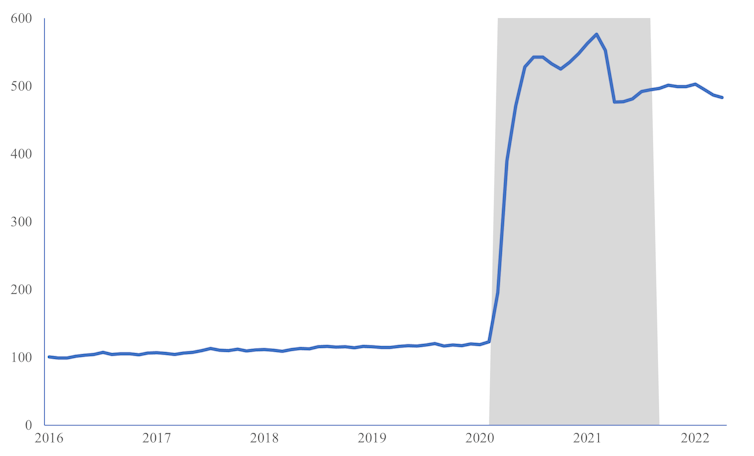

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Bank of Canada introduced a large number of lending programs and used non-interest rate tools — known as nonconventional monetary policy — to provide liquidity to the financial markets and stimulate the economy.

This led to an unprecedented increase in the Bank of Canada’s balance sheet, with the central bank buying more than half a trillion dollars of financial assets, primarily in the form of Government of Canada securities. Before the pandemic, the Bank of Canada’s holdings of securities were about $100 billion.

The expansion in the Bank of Canada’s balance sheet led to a huge injection of liquidity in the financial system and led to an increase in the reserves that commercial banks have in their accounts with the Bank of Canada. In fact, these reserves increased by more than 1,500 times their pre-COVID amount. Such increases in bank reserves are generally considered to be inflationary.

Restoring faith in the Bank of Canada

The Bank of Canada’s recent aggressive monetary tightening will be transmitted to the real economy through higher interest rates and lower asset prices (including housing prices), and will most likely kill the post-COVID economic expansion.

With inflation seemingly out of control, central banks appear to be losing credibility. The public trusts central banks to protect the buying power of money, but the increasing cost of living is eroding this trust.

The Bank of Canada, and other central banks including the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, are all desperately trying to fight inflation and restore their credibility.

In Canada, this restoration has involved the unprecedented increases in the Bank of Canada’s policy rate that have taken place since the beginning of the year.

Curiously, other countries that are facing the same supply chain problems and higher energy prices as us are not struggling with inflation as high as ours. For example, the inflation rate in Switzerland is 3.4 per cent, in Japan is 2.3 per cent, and in China is 2.4 per cent. But why this is the case is another conversation entirely.

Apostolos Serletis does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.