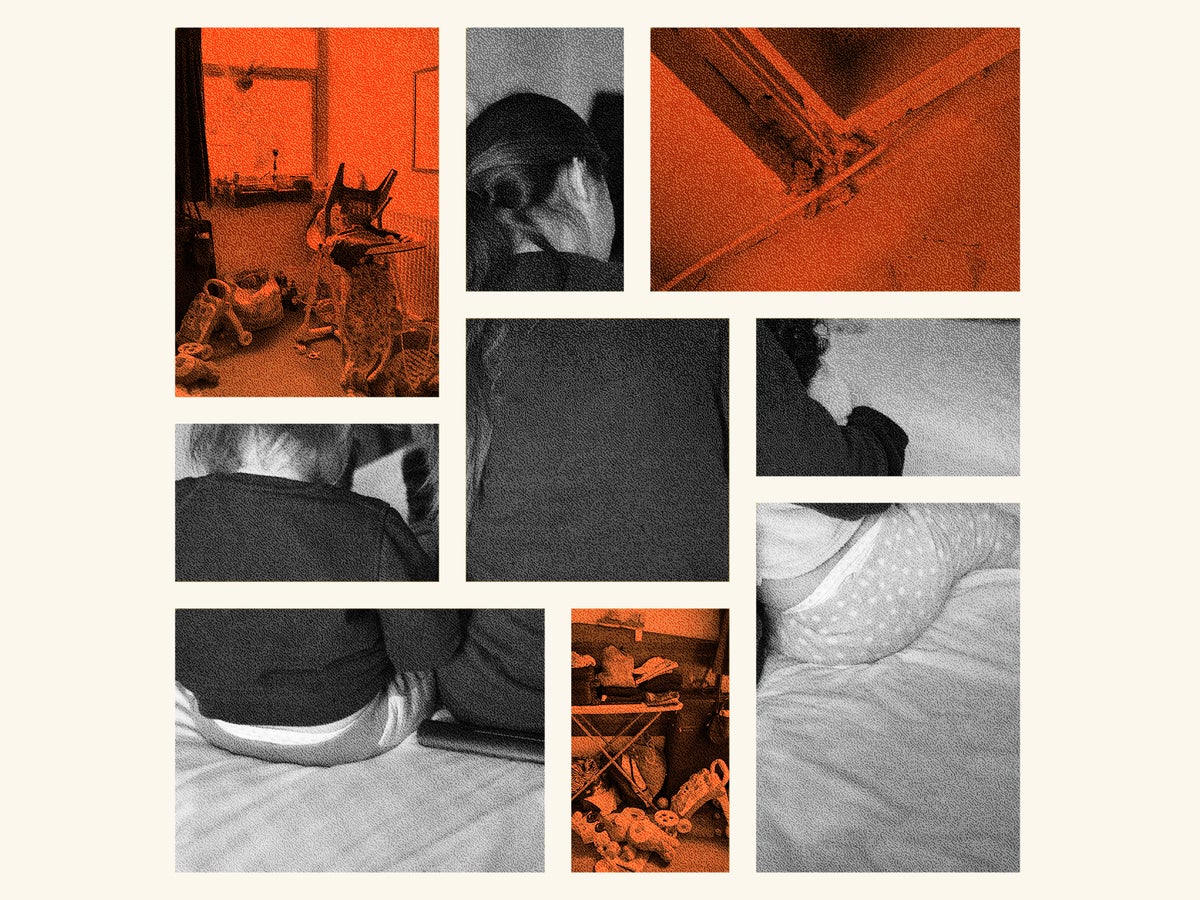

In a small darkened room where the scent of damp lingers, two toddlers sit quietly on a double bed. The sisters, Elva and Gabriela, stare vacantly at the blotched ceiling and mould-speckled walls. Their father, Carlos, stands by despairingly. This cramped space is all his daughters know.

The El Salvadorian national arrived in the UK last September with his wife, Aline, and their two girls – aged one and two – after being “caught in the crossfire” of gang violence. They had hoped to find a place for their children to grow up in relative safety and comfort. Instead, they have been stuck in a hotel room perched on a busy A-road in west London for eight months, banned from working and with only £32 a week for the family to live on.

Two double beds pushed together take up most of the room. The small amount of space that remains is filled with household items – an ironing board, a small fridge, a high chair, toys. Wedged in a corner is a desk cluttered with baby wipes, formula and bottles, along with an electric hob and kitchen utensils.

“My babies are coughing because of the fungus,” says Carlos, 35, a man of slender build with weary eyes indicating regular sleepless nights. “A month ago we got bed bugs. They got pest control in only last week. We were waiting a long time. My babies were uncomfortable. They couldn’t sleep.”

A tiny bathroom en suite is filled with drying clothes and a pile of items – bags, children’s books, shoes – that do not fit in the main room. In the sink is a wooden spoon and a bottle of washing-up liquid beside the tap along with the family’s toothbrushes.

“I can’t provide for them; I feel useless,” says Carlos, close to tears. “As a father, I feel useless.”

While Boris Johnson and home secretary Priti Patel focus on immigration plans such as the controversial Rwanda deportation policy or finding homes for Ukrainian refugees, the issues faced by Carlos and his family are the reality for an increasing number of asylum seekers, forced to live in government-funded hotels while they await decisions on their claims to stay in the UK. This form of housing used to be rare, but surged during the pandemic as Covid restrictions meant housing was not available. At the time, ministers described it as a “temporary measure”.

By last month, despite the end of Covid rules, some 28,621 asylum seekers were living in 220 hotels across the country, up from 10,319 in February 2021 – when the Home Office pledged to “accelerate” the movement of asylum seekers out of hotels and into housing – according to figures seen by The Independent. The hotels are run by three companies: Serco, Clearsprings Ready Homes and Mears Group.

Government guidance states that asylum seekers should not be held in this “contingency accommodation” for more than 35 days, but figures obtained under the Freedom of Information Act reveal that, as of the end of September 2021, two thirds of all asylum seekers in hotels – including 1,079 children – had passed that limit. Nearly 1,000 had spent more than six months in hotel rooms, with 356 longer than a year. The Home Office declined to provide more recent data, claiming it needed to consider whether the disclosure would “prejudice the effective conduct of public affairs”.

As the numbers rise, so too do the fears for asylum seekers. A welfare concern about asylum seekers in hotels is reported to the Home Office every 30 minutes, on average, according to the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration (ICIBI).

In London, a severely disabled teenage girl from Kuwait is spending her ninth month in a London hotel room, forced to lie on the floor, without a bathroom in which she can wash properly. In Skegness, a young man from Kurdistan is forced to wait days before receiving any medical attention for intense stomach pains, ultimately being taken to hospital by ambulance. Two small children are left without anywhere to play except a car park or exposed hotel corridor.

Their cases are far from isolated. The problem is growing and, experts warn, cannot continue without a human cost.

In pain for days – but ignored

When Ahmed arrived in Britain last November, he was already traumatised. The Iraqi Kurdish national had fled from his home due to threats made because of his political beliefs, and made his way to France. From there, he paid smugglers to travel by small boat to the UK, arriving just hours before 27 people died attempting the dangerous crossing.

The 20-year-old has been in a hotel in a rural part of Skegness, Lincolnshire, for seven months. He says that several weeks after being placed there he began having stomach pains. He says he tried to ask for help, but to no avail.

“Every time I went down to tell the hotel staff they would tell me I could go to the GP myself, but I was in too much pain and I didn’t have money for a taxi so I couldn’t go,” he says. “They said they would call a GP for me. I did that a couple of times, but they never came. The hotel staff didn’t say why. They kept saying: ‘Go up to your room; the GP will come.’ I was begging them to let me see a GP for three days. I was in so much pain. It was constant.”

Several days later, the pain became so excruciating during the night that Ahmed cried out for help. An ambulance was called and arrived an hour later. He was taken to hospital, where he stayed overnight. He says there was no interpreter there so his diagnosis wasn’t properly communicated to him, but he was given an injection and medication.

Figures obtained by The Independent reveal that many asylum seekers such as Ahmed have needed ambulances called out to hotels. The data, disclosed through Freedom of Information requests, shows that just 27 of the 226 hotels were responsible for 1,495 callouts in the year to last October – more than one a week. Of these, more than half led to a patient being taken to hospital.

Experts say this is a symptom of a lack of access to healthcare. The contractors running the hotels on behalf of the Home Office are required to support people with registering with GPs, but those working with asylum seekers warn that this does not always happen.

Dr Durga Sivasathiaseelan, mobile clinic coordinator at the charity Doctors of the World, said that although the charity was initially able to support asylum seekers in hotels with registering with GPs and accessing health services, a change in the way the Home Office shares data in January had prevented them from helping.

She said: “This has made it very difficult to support people. We don’t know who is there. Things have got significantly worse in terms of access to healthcare for people in hotels – I’m very worried for those who now won’t be able to access healthcare.”

A Home Office spokesperson said it worked closely with the NHS, local councils and NGOs to ensure access to healthcare. They also pointed to the ICIBI finding that 92 per cent of service providers were helping asylum seekers find healthcare, and said there were “robust processes” to ensure someone at risk was referred to appropriate agencies.

Serco said that all of the asylum seekers in its care were registered with local GPs. Mears said it had “worked closely with relevant local health teams in all areas”.

Handa Majed, founder of the charity Kurdish Umbrella, which supports people in hotels, said: “New arrivals scarcely receive the essential services and support they require while in Home Office hotel accommodation. Staff do not speak their language, their mental health needs are not understood or catered for, and healthcare and education are absent.”

Their living conditions are intolerable— Emma Dawson, Duncan Lewis Solicitors

Ahmed is still struggling to cope psychologically. Remembering the days before the ambulance was called, he says: “It felt horrible, terrible, lonely. I felt very alone. I started to feel ashamed of going down and asking for help. I didn’t know the language. I felt very isolated. The staff barely noticed me, even though they knew I was in pain.

“I feel very depressed and I have spoken to the staff about seeing a therapist. They either say ‘we will get back to you’ or that I can go and see one myself, or reach out to organisations – but I don’t know how to find these organisations.

“I’m very traumatised from the journey. The hotels are in a really bad shape here. We’re all depressed and we have nothing to do. We don’t know what’s going to happen to us.”

‘Intolerable’ conditions for a disabled child

Lying on a thinly carpeted hotel room floor, 13-year-old Sara groans and writhes on her back. The disabled Kuwaiti national, wearing a pink-patterned set of pyjamas, is in visible discomfort. Her mother and elder brother feel powerless to help her.

“She gets suffocated in this space. It’s not appropriate for her needs,” says Ayman, her 20-year-old brother. “She needs her own space, but the room is very small. The bathroom is not adequate. We have to put her on the floor and she slides around. It’s really hard.”

The family – Ayman, Sara, their mother and two younger children – arrived in the UK last August. As members of the stateless minority group known as Bidoons, in Kuwait they had for years been denied access to basic services and rights such as education and healthcare.

The children’s father was imprisoned after protesting for equal rights, and they do not know where he is.

“It was a journey with many difficulties,” says Ayman, describing crossing the English Channel in a small boat. “It was a good job we had other people to help with carrying Sara, putting her in a blanket.” Several hours later, they arrived on the Kent coast and were taken to the east London hotel.

The family has been given a wheelchair and their room is on the ground floor, but the hotel is on a busy road and there are few places they can take her. Ayman is keen to make it clear the family is “grateful” for accommodation, but he is angry that Sara is not receiving the care she needs.

“They say we need proof of her disability, but we don’t have medical documents. You can just look at her and see what needs she has, but no one from the Home Office has come to see her,” he says.

To make the situation worse, the family was recently diagnosed with scabies and, despite requests from their GP that bedding and towels be boil-washed immediately, the hotel refused to change its nominated laundry day and they were left to sleep in the used bedding for a further six nights.

Lawyers have been trying to get the family moved into more appropriate housing for months. Despite the Home Office confirming in legal correspondence in January that Sara required wheelchair-accessible accommodation, the family remains in the same place nearly six months on. Emma Dawson of Duncan Lewis Solicitors, who is representing the family, says legal obligations are not being met.

“Their living conditions are intolerable,” she says. “The impact of the living situation and the unexplained delay in moving the family out of the hotel has reached an unacceptable level.”

Nowhere for children to play

Wahid and Fatima sit on the edge of a single bed, with three-year-old Jahmal perched on Fatima’s lap, staring blankly out of the small window. They live and sleep within these four walls. The parents have tried to keep the space tidy, but with the clothes hanging up to dry and kitchen appliances and other items together in the single bedroom, it cannot help but feel cluttered and claustrophobic.

The Syrian couple have four other children, aged between nine and 14, who are in school. They sleep in a similar room next door. It has been this way since the family arrived in the UK in June 2021 and were placed in this west London hotel.

There is nowhere outside the bedrooms for the children to play – only a draughty corridor, which leads to a concrete car park. The Home Office claims security officers are on site 24 hours a day, but when The Independent visits there is no security presence; anyone could walk in.

“The children can only play in the rooms. The car park isn’t safe for them. Drunks come out of the pub opposite,” says Wahid, 49. “This place is not for families. It is very dirty. There are mice everywhere. Every time our youngest kid sees a mouse he gets a panic attack.”

He says: “We get £56 a week for all of us – we use this money to buy food for the kids. With £22 of this allowance going on transport for the children to get to school, the money doesn’t stretch very far.

“I was a truck driver and a farmer in Syria. It would mean a lot for me to have a proper job here. I would like to be able to afford basic things for my family.”

The family left Syria in 2014 and travelled to Austria, where they lived for six years – for a while they were happy there. But Wahid says they faced growing racism. He says: “Our kids used to go to school, but they couldn’t make a relationship with the other kids because they were refugees. People told us we had to go back to Syria. Sometimes, Austrians would drop whisky over Fatima’s head because of her headscarf.”

Fatima, a petite woman wearing a black headscarf, says: “We didn’t feel safe. We thought about going back to Syria, but anyone who left after 2011 is seen as being against the regime and we could be subject to detention. So we took a risk.”

People who have been forced to flee their homes need stability, security and to feel safe— Jon Featonby, British Red Cross

Embarking on what Fatima describes as the “death journey”, the family travelled to northern France and paid €4,000 (£3,400) to cross the Channel. Setting off at 2am, they were told by the smugglers that it would take around two hours – but, along with about 43 other people, they spent nine hours in the dinghy and a further two in a rescue boat.

On arriving in the UK, the children didn’t start school for four months, which Fatima says was a “disaster”. They are all now enjoying school, which is a relief for their parents, but the youngsters still struggle.

“We’ve been here for so long,” says the couple’s eldest daughter, Hana, aged 12, who speaks in near-perfect English. She is standing in the hotel’s car park with her younger brother. “It’s horrible because there’s no space for us here. I like school, but being in this place is not good.”

The children are lucky that they have started school – not all asylum-seeking children in hotels have. The ICIBI report, released earlier this month, found those in hotels on the outskirts of towns or residential areas were less likely to secure school places.

In one case, inspectors met a single mother with three young children, all living in one small room. The eldest child, who was around eight years old, was waiting for a school place. “He had nothing to do other than play games on a mobile phone,” inspectors said.

A ‘disastrous’ situation

The backdrop to these issues is huge amounts of taxpayers’ money being handed to the three contractors employed by the Home Office to maintain hotels – Serco, Mears and Clearsprings Ready Homes. Their deal with the Home Office, which began in 2019, is worth £4.5bn over 10 years.

The cost to the taxpayer for the hotels alone is now £3.6m a day – or £1.3bn a year – above and beyond what was agreed due to the numbers involved, for housing condemned by campaigners as unsuitable to be lived in for long periods by people who have often fled horrendous conditions. A further £1.2m a day is spent on refugees who fled Afghanistan, 12,000 of whom are in hotels, according to data released in February.

Clearsprings Ready Homes, which manages the London hotels where Wahid and Fatima, Carlos and his family and Sara and her family live, says: “Whenever issues are raised or defects are identified, Ready Homes will undertake a full investigation and ensure that those issues are addressed as soon as possible.” The company did not comment on concerns about GP access.

Meanwhile, government figures published last month reveal that the pace of Home Office processing of asylum claims has slowed considerably, with a record 109,735 people waiting for a decision, 300 per cent more than four years ago. Some 73,207 men, women and children have been waiting for decisions for more than the service standard of six months.

Shadow immigration minister Stephen Kinnock says: “The disastrous situation with asylum hotels is emblematic of the incompetence and indifference of Priti Patel’s Home Office, which is not fit for purpose. Priti Patel needs to get her house in order, and fast.”

Maddie Harris, founder and director of the Humans for Rights Network, says the organisation has helped more than 150 unaccompanied children, as well as adults who had lost limbs to conflict and families with small children who had been unable to get help from contractors in hotels.

She says: “Despite the government’s claim that accommodating people seeking safety in hotels is a temporary emergency policy, it continues to open them and has learnt no lessons regarding the harm that these settings do to people’s physical and mental health.”

When approached for comment, the Home Office says the Nationality and Borders Act will “fix the broken asylum system” and that asylum seekers are provided with “safe and secure accommodation, ensuring no one is destitute”.

But the British Red Cross has also warns that more action is needed to help asylum seekers become part of local communities. Jon Featonby, policy and advocacy manager for refugee and asylum, says: “We know from our work supporting men, women and children who have been living in hotels just how unsuitable they are for people to spend several weeks in, yet alone more than a year. People who have been forced to flee their homes need stability, security and to feel safe.”

After 11 months in their hotel, Wahid, Fatima and their five children are finally moved into more suitable accommodation. But for Carlos and Aline, Ahmed, Sara and their families, the wait goes on to see if they can make it out of a broken system before it breaks them.

Names have been changed to protect identities

Additional reporting by Furvah Shah and Aisha Rimi