QAGOMA’s Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art opened over the weekend with a flurry of artist talks, panel discussions and performances.

With more than 70 artists and artistic projects from Australia, the Pacific and Asia, the triennial is a warm celebration of the diversity of the region’s artistic practices.

Unlike thematically organised exhibitions, the triennial’s curatorial focus has remained remarkably consistent since its inception in 1993. Its focus has always been surveying the most exciting and original art of our region.

One of the risks of this strategy is the challenge of remaining fresh and innovative. The solution to this is twofold.

First, the decision in the 1990s not to appoint a freelance artistic director resulted in the opportunity to develop the authority of knowledge in-house.

Now led by Tarun Nagesh, the curatorial team wields a formidable depth of expertise. This is further strengthened with curatorial partnerships in countries throughout the region. As a result, the connections with individual practitioners demonstrate an authenticity that can often go awry in large-scale exhibitions.

Second, the triennial has never been isolated from broader social and political conversations. As a result, this year sees key concerns emerge such as labour migration, resource extraction, and expressions of home and community.

Untold stories

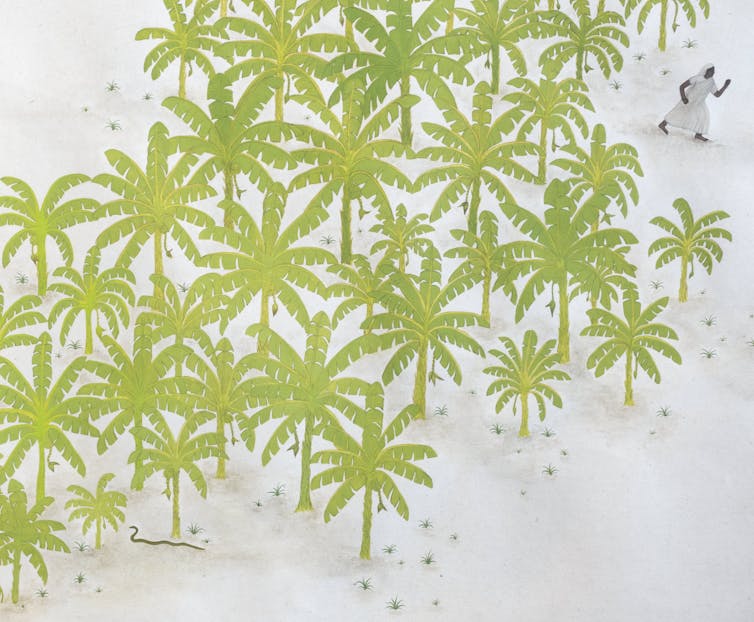

Consider, for example, Sancintya Mohini Simpson’s extraordinary nine panel painting kūlī / khulā (2024).

Extending horizontally across the gallery walls, the delicate handmade wasli paper depicts miniature figures in a landscape.

Simpson is simultaneously entering into a long history of miniature painting, as well as investigating gaps in the historical archive of the practice of indentured labour and forced migration.

Simpson’s research is deeply personal and investigates intergenerational trauma. She is a descendant of bonded labourers sent from South India to South Africa to work on colonial sugar plantations in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Simpson is focused on giving visibility to the women’s histories: their labour, lives and relationships.

Tully Arnot’s ceramic birds are easily overlooked. Mischievously installed in unexpected spaces, the birds are perched on sticks, twittering and contributing to the ambient soundscape.

There is a darker side to Arnot’s Bird Song (2024): the tweets are drawn from data and translated into sound through electronics and pumps. The work is a mediation on mass extinction.

She asks: will the artificial be the last mode of interaction with animals?

Local communities

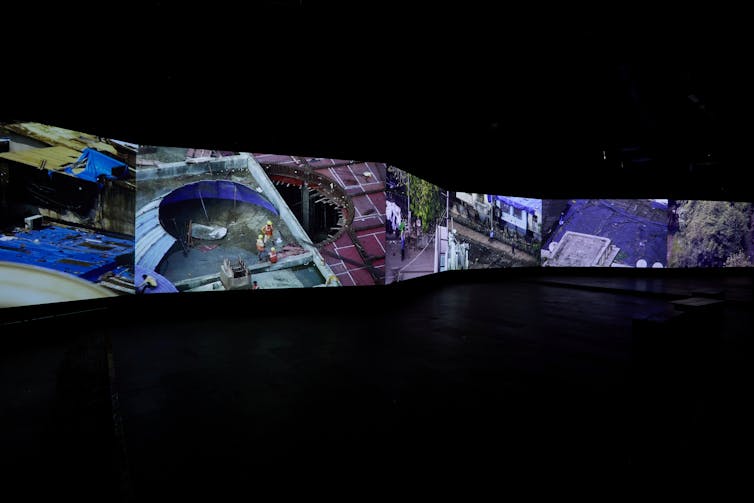

One highly engaging seven-channel video installation is by Mumbai-based artists’ collective CAMP.

Using a remote-controlled pan-tilt-zoom camera, the film was created entirely from a CCTV camera located on the 35th floor of a building in south Mumbai.

Each screen gives a distinct view of the individual camera movements, as the camera’s mechanical gaze slowly surveys the scene.

CAMP have long been interested in the technological possibilities offered by CCTV. At one point in the video, the spectator’s assumed anonymity is disrupted by a group of people engaging directly with the camera.

The toll of resource extraction on local communities and the environment in northern Vietnam is the subject of Lê Giang’s extraordinary gem paintings.

Emerging out of the gloom in a darkened gallery space, the paintings appear like shimmering stones.

The popularity of precious and semi-precious stones such as ruby and sapphire has led to deforestation, the pollution of waterways and human rights abuses in northern Vietnam, where the mines are located. This in turn has led to the call for sustainable gemstone mining practices.

The artisanal practice of gem painting involves taking the impure leftovers from gem-mining, and crushing to create a fine, glittering powder. The powder is sprinkled onto Perspex, fixed with glue and transformed into sparkling paintings.

Lê Giang worked with local gem painters to create a series of landscapes that pay homage to this regional vernacular practice. They also deliver a sharp rebuke to the environmental costs borne by an insatiable appetite for luxury goods.

Now is the time for collaboration

Of particular note is the richness and depth of the film programming at GOMA’s Australian Cinémathèque.

This commenced with a film series dedicated to Malaysian-born, film director Tsai Ming-liang and will continue over the exhibition’s duration with a thematic selection of science fiction films from across Asia and the Pacific.

Crucially, with the cost of living crisis, the triennial is free, making QAGOMA an attractive destination for families and younger visitors over the upcoming summer months. This is bolstered by comprehensive children’s programming.

This decades-long investment in local communities has paid off. When I quiz incoming undergraduates at the commencement of each academic teaching year, they frequently cite their formative artistic memories and art experiences being shaped by the triennial.

As the region readies itself for a Trump presidency and the distinct possibility of trade and economic instability, the triennial’s embodiment of soft regional diplomacy comes acutely into view. Now is the time for collaboration and respectful discourse.

Chari Larsson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.