The ‘Anna Bhagya’ scheme is one of the five main election promises made by the Congress party in the run-up to the Karnataka Assembly elections, in May 2023, with the pledge to provide an additional five kilograms of free rice to every member of a Below Poverty Line household. The Congress party’s (lack of) vision is as disappointing as the central government’s policy.

Explained | What is Karnataka vs. Centre row over free rice scheme?

Even the fiercest critics of the PDS were compelled to recognise its key role in protecting people from hunger during the COVID-19 -related lockdowns. Many believe that the coverage of 80 crore people (during the pandemic) is not only laudable (it is) but also adequate (it is not). Besides inadequate coverage, in most States, the PDS does not provide nutritious food items such as pulses and oil. These are the two lacunae that should be rectified.

In late March 2020, the central government announced that it would double rations for those who have ration cards. For the situation then, this was a good move. But even then it did nothing for those who did not have ration cards — and there were plenty of them.

The National Food Security Act (NFSA) 2013 expanded the coverage of the PDS substantially. So, why are so many people still without ration cards? The law mandates that 50% of the urban and 75% of the rural populations must be covered by the PDS. The central government combined these coverage ratios (adjusted to account for State-wise poverty levels) with the 2011 population numbers to determine each State’s ‘quota’ of ration cards. As the NFSA rolled out (staggered across States between 2013-2017), PDS coverage climbed from under 500 million to reach 800 million — its current level.

The problem is that even in 2023, India continues to use the 2011 Census population because the central government is blissfully evading its obligation to conduct the 2021 Census. The NFSA requires that the latest completed Census be used to calculate the total PDS coverage. The government, thus, has a convenient excuse to ignore demands to expand PDS coverage to account for population growth. At the all-India level, the under-coverage results in the exclusion of an estimated 113 million people, of whom 1.1 million are in Karnataka.

Some States use their own budgets to “top up” PDS coverage through the Open Market Sale Scheme (OMSS) — for example, Tamil Nadu — or local procurement — for example, Odisha and Chhattisgarh. Curiously, no State government – not even those led by non-Bharatiya Janata Party parties — appears to have taken up the issue of under-coverage due to outdated population estimates with the central government.

Discontinuation of the OMSS

The Food Corporation of India (FCI) procures grain for three broad purposes. One, it supports producers by procuring (mainly) wheat and rice at minimum support prices (MSP). Two, the central government uses this to meet the needs of the PDS (providing five kilograms a person every month free to NFSA households), a consumer subsidy. Three, the stocks are used for price stabilisation through the OMSS.

The OMSS has been in the news recently. It is crucial for those States that go beyond NFSA entitlements. This is especially true for States such as Tamil Nadu that rely on OMSS bulk sales by the FCI to support their unique universal PDS. During COVID-19, many States used OMSS grain to run community kitchens and supply food packets. This is the route that the Karnataka government was relying on to fulfil its ‘Anna Bhagya’ promise, roughly doubling rice benefits from their current level. When Karnataka sought OMSS grain for the ‘Anna Bhagya’ promise, the central government said that it would no longer allow States to buy OMSS grain.

The central government has given three reasons for the discontinuation of OMSS for State governments. One, it claims that the OMSS can perform its price stabilisation role better if the grain is released through the market rather than through States/the PDS. This is not a convincing argument as the two are more or less equivalent. In fact, there is no guarantee that private traders who get OMSS rice at fixed prices will pass on the benefits to consumers.

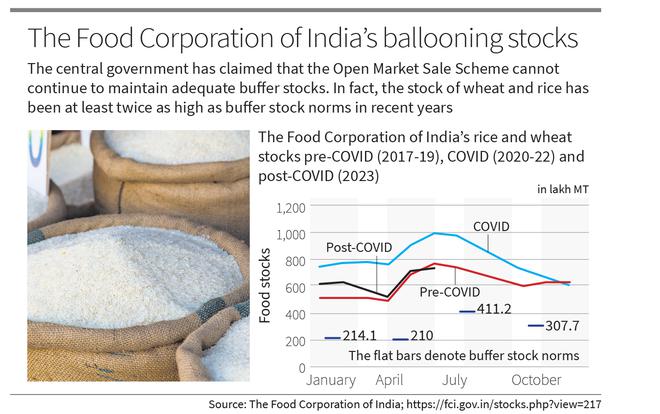

Two, the central government has expressed worries about maintaining grain stocks at a “comfortable level”. While it may be true that procurement this year will be lower than previous years, what the government fails to mention is that its current stock position is, in fact, very comfortable. For the past five years, including when the central government was providing double rations as relief during the COVID-19 pandemic, stocks have tended to be twice as high as the buffer stock norms (see chart).

Three, it has reportedly stated that “State governments are going to give the foodgrains to the same beneficiaries” as under the NFSA or for beneficiaries of State schemes, and that the central government has an obligation to the 600 million people who are not covered by the PDS.

The central government’s obligation to the 600 million people outside the PDS is best met by other means — for example updating PDS coverage by using the projected population for 2023. Had the Congress in Karnataka promised an expansion of the PDS, it could have escaped this reasoning given by the central government. Blocking OMSS sales to States suggests that while the central government is unwilling to spend on this, it wants to prevent State governments from doing so.

Options before the Karnataka government

The Congress party’s ‘Anna Bhagya’ promise betrayed a lack of vision for food security. Why promise more rice to those who already get five kilograms each month, especially when over one million people in the State, who should be a part of the PDS are excluded because of outdated Census figures. Why not extend NFSA benefits to them instead?

It is also time to think beyond rice and wheat through the PDS. When it comes to Karnataka’s neighbours such as Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh and elsewhere (in Himachal Pradesh), PDS ration card holders get heavily subsidised pulses and oil through the PDS.

The Karnataka government is well placed to expand its PDS to include 1.1 million excluded people and provide them with five kilograms of grains a person every month (either rice or millets or a combination of the two). Procuring millets to meet the obligations of an expanded PDS is a sensible option, at least temporarily. Millets such as ragi are part of the local diet anyway and are equally if not more nutritious than rice. Karnataka is a major producer of millets; if the State procures at MSP, it could support its farmers as well as consumers.

Editorial | Limits of expansion: On the controversy over the Open Market Sale Scheme

For existing PDS beneficiaries (who were promised ‘Anna Bhagya’ rice) and new card holders, the State can provide them two kilograms of dal and a kilogram/litre of oil for free each month. The expansion and diversification of the PDS will cost the State roughly the same as the ‘Anna Bhagya’ promise. More importantly, compared with the cash transfer to existing PDS households that the State is currently considering, an expanded and diversified PDS is more valuable from the point of view of social (as opposed to individual) benefits.

Reetika Khera is Professor of Economics at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi