Review: 2022 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Free/State, Art Gallery of South Australia

South Australia has always traded on its convict-free history and its founding as a “great and free” colony. Sebastian Goldspink’s 2022 Adelaide Biennial of Australian Art: Free/State is a conceptual riposte to this colonial settler history, but it is much more. It is a nuanced play on the words “free” and the “state”, and the zones in between.

The pandemic has, of necessity, turned up the heat on ideas around freedom and the place of the state; this Biennial showing the work of 25 multi-generational artists is very much of its time.

Fittingly, the first work encountered is of Ukrainian émigré Stanislava Pinchuk whose text etched into marble plinths calls for safe passage for displaced people. On the opening of the Biennial, it echoes daily scenes in her home country, the site of a modern-day tragedy.

Pinchuk’s evocative installation, The Wine Dark Sea, carries text from unidentified refugees held on Manus Island and Nauru, and from Homer’s Odysseus who was homeless following the Trojan wars.

Urgency and despair is palpable in these etched messages: “Odysseus has lost hope”; “[REDACTED] did not want to come to this island.”

Running out of time

This 16th iteration of the Adelaide Biennial of Australian art gives visual form to the big ideas surrounding freedom and equality, and failures, especially of the colonial state.

Viewers enter Free/State through Kate Scardifield’s bright orange navigational sails adorning the gallery’s façade. We are reminded of a major failure of the state in relation to climate change: the colour orange is conventionally used by sailors in an emergency.

For Scardifield, the role of art is to make visible what is invisible. Her exhibit within the gallery, Urgent is the rhythm, is a classical column made from carbon capture bricks. She challenges the museological world to consider it could capture carbon.

Tom Polo’s work in the Biennial sits squarely in the zone between “free” and “the state”: the space where chance enters the arena. His large semi-figurative, semi-abstract paintings stand amid the permanent works on display in the Australian art galleries, inviting audience members to find connections between his work and 18th, 19th and 20th century art.

Polo’s paintings as theatrical gestures challenge easy looking. Then there is his Clockwatch (end/during) sitting centrally on a large blue wall in a central space of the gallery, rather like the clock in any central station. But unlike a trusted clock, his is programmed for random actions.

Sometimes it is an analogue clock, at other times it becomes a talking clock face. If you listen carefully, you can even hear it question its existence: “there is not much time left”.

Our online lives

One of the most ubiquitous outcomes of life under the pandemic has been communication via zoom meetings. Julie Rrap’s Write Me responds to the facial images Zoom conveys and the phenomenon of people hiding behind their keyboards. Rrap’s keyboard has become 26 warped versions of the artist’s face, one for each letter of the alphabet.

When we retreat to screens, we lose the social contract of communicating in public space.

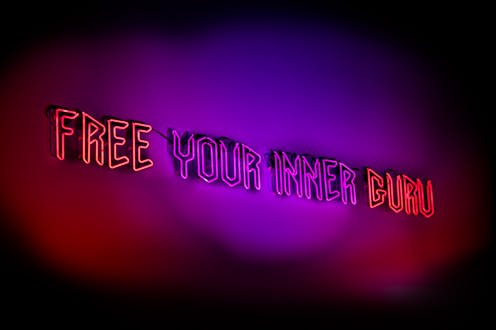

Other artists have turned to transcending the state via spiritual and otherworldly quests.

During the pandemic people turned to faceless algorithms like Google to answer life’s burning questions, so in Open Channels, Kate Mitchell constructs a conference call screen with nine psychics of the spirit world answering 83 questions.

A theatrical exhibition

The curatorial hand of Goldspink, a Burramattagal man, is delicate in Free/State. His brief to artists to explore ideas of freedom, the state and everything in between has led to a philosophical journey by a group of artists who – during numerous lockdowns during the pandemic – have looked within.

Angela Valamanesh turned to her garden and found beauty and resilience in the thorns of her rosebush in Morticia’s garden; Hossein Valamanesh transformed household gravel into a magical constellation of golden stars.

The post-colonial and decolonial work speaking to the failure of the state is strong.

Kamilaroi/Gamilaraay artist Dennis Golding has transformed Victorian lacework on terrace houses in Redfern into an Aboriginal chandelier by subverting and claiming European domestic design features.

Kamilaroi artist Reko Rennie turned to a restored bright pink Holden Monaro to journey around urban sites of initiation into his cultural values. This journey takes place against a stunning soundscape by Yorta Yorta artist Deborah Cheetham whose music is infused with Kamilaroi language to honour Rennie’s grandmother who was never able to pursue a musical career.

Even a delightful element of anarchy surfaced in the opening satirical performance by Loren Kronemyer and Pony Express in Abolish the Olympics in which she performed 33 Olympic sports in one hour. Here, Pony Express describe themselves as social justice weightlifters whose aim is exposing the economic malpractice of the Olympics.

And there is more, including Shaun Gladwell’s slow seductive glimpse into street culture and the inevitable curbing of freedom for some who transgress in his video Homo Suburbiensis.

Free/State is a performative exhibition calling on viewers to engage and explore, to leave behind their closed world of lockdowns. It is an intensely theatrical exhibition, as good exhibitions should be. Goldspink has set in motion a philosophical journey centring around human resilience and creativity in a time of uncertainty.

Free/State is at the Art Gallery of South Australia until June 5.

Read more: Australian art has lost two of its greats. Vale Ann Newmarch and Hossein Valamanesh

Catherine Speck has received funding from the Australian Research Council to investigate art exhibitions (with Joanna Mendelssohn, Catherine De Lorenzo and Alison Inglis).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.