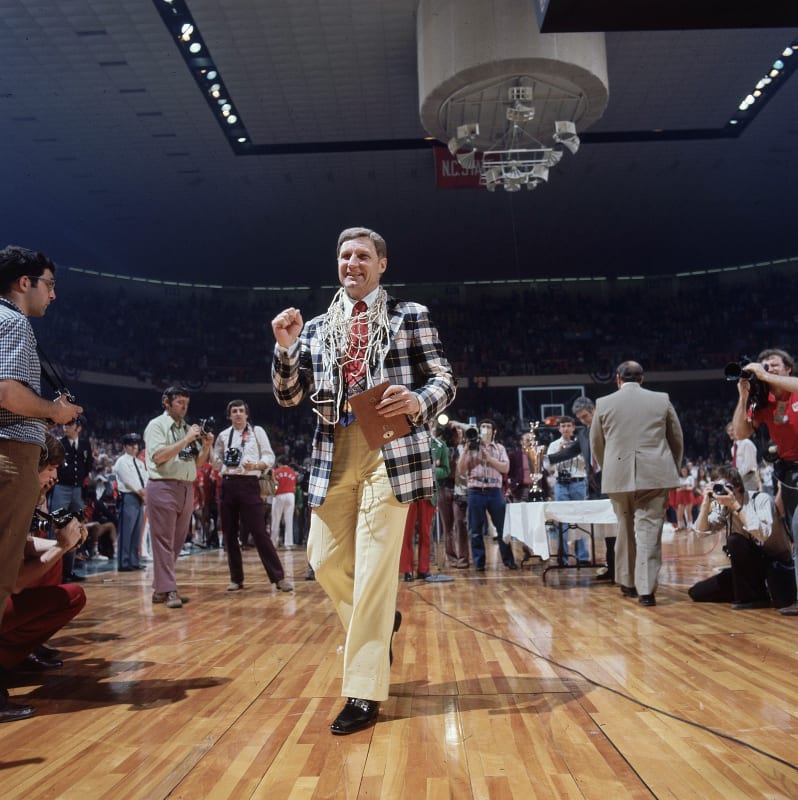

When it was finally over, late on the night of Saturday, March 9, 1974, Monte Towe didn’t bother joining the celebratory net cutting. Instead, the tiny North Carolina State Wolfpack point guard sat next to the wife of his coach, Joan Sloan, and hugged her through tears.

“I felt a lot of pressure,” Towe says. “We had won almost every game we’d ever been in, but we still had to win one more to get where we wanted to go. Afterward, I was just drained by the pressure of the situation and the high level of the game.”

The level of the game was, by acclimation of those in the Atlantic Coast Conference, unparalleled. North Carolina State 103, Maryland 100, in overtime of an ACC tournament final played in a smoke-filled Greensboro Coliseum, during the days before multiple NCAA bids for the same conference, was declared by many to be the greatest men’s college basketball game ever played. It retained that gilded designation until Christian Laettner stuck a dagger in the Kentucky Wildcats in 1992. Even now, 50 years later, you can still find a few holdouts who believe that Wolfpack vs. Terrapins showdown is the true gold standard of the sport—a 203-point masterpiece in the days before the shot clock or the three-point arc.

“We couldn’t stop them,” Towe says. “They couldn’t stop us.”

Lane Stewart/Sports Illustrated

The stakes for the last great conference tournament final were massive: North Carolina State would go on to win its first national championship, capping a 57–1 run over two seasons, while Maryland’s quest for a title (or even a Final Four berth) would remain unfulfilled for decades longer. The talent was exalted: three players from that game were taken among the first 13 picks of the 1974 NBA draft—NC State superstar David Thompson was the No. 1 pick in the American Basketball Association (ABA) draft a year later; Maryland guard John Lucas was the No. 1 pick in the ’76 NBA draft; and Wolfpack forward Tim Stoddard went on to become a World Series champion pitcher. The coaches had strong personalities: Maryland’s Lefty Driesell was a combative quipster, NC State’s Norm Sloan was a nonstop promoter and both were consumed with beating North Carolina’s Dean Smith.

And the game would tangibly impact the future of March Madness: The next year, the NCAA tourney expanded from 25 to 32 teams and conferences were allowed multiple representatives. “It truly changed college sports,” Maryland forward Tom McMillen says.

The 1973–74 Maryland team would be the last of its kind—good enough to compete for a national title but blocked by its nemesis from even getting into the Big Dance. “I think we would have been in the Final Four,” Maryland center Len Elmore says. The Terrapins declined an invitation to the NIT the following day, not interested in that consolation prize.

That brought to an end the Maryland careers of Elmore (the No. 13 pick in the draft) and McMillen (the No. 9 pick), both of whom were huge recruiting coups for Driesell. They would go on to remarkable professional lives: Elmore played 10 years in the NBA, became a prominent TV analyst, went to Harvard Law School, became an assistant district attorney in Brooklyn and currently is a full-time faculty member at Columbia; McMillen was a Rhodes scholar, had an 11-year NBA career, spent six years as a U.S. Congressman, joined the Maryland board of regents and currently is a prominent voice in college sports as president of the Lead1 Association that advocates for athletic directors at FBS schools.

But even half a century later, as accomplished men in their 70s, the sting of losing that game hasn’t completely subsided. Asked his strongest memory of that night in Greensboro, Elmore says flatly, “We lost.”

He’s never watched a full replay of the game.

“Honestly, it’s just hard,” Elmore says. “You just second-guess yourself. The aesthetics of the game, I can look back and appreciate it; I can listen to folks glorify the game. But it’s hard.”

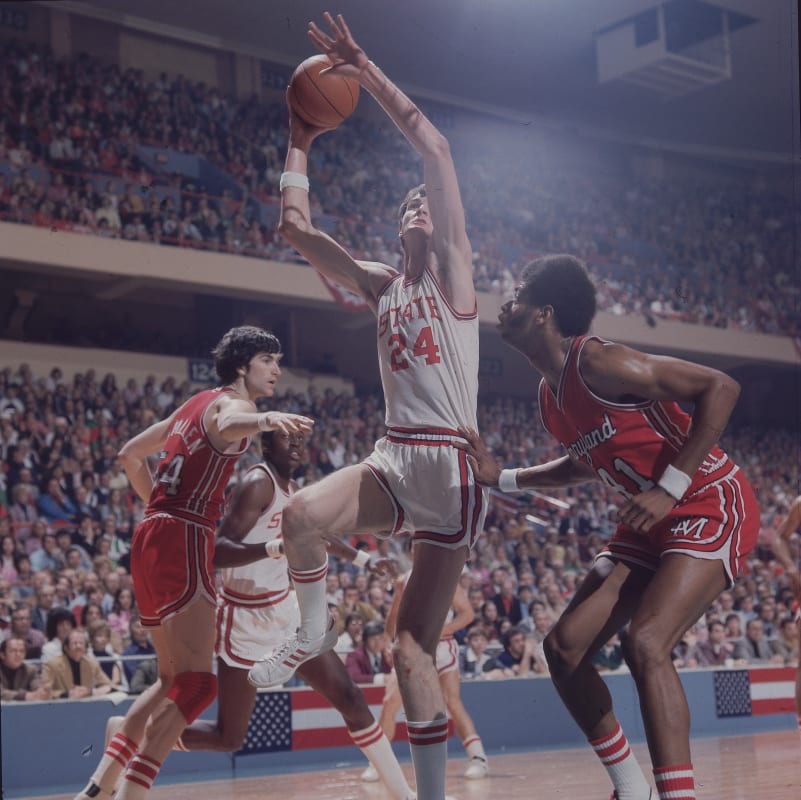

Lane Stewart/Sports Illustrated

The hardest part for Elmore was watching the man he was primarily guarding, Tommy Burleson, play the game of his life. The two vastly different big men had spent three seasons knocking heads in the paint (freshmen were ineligible for varsity play then), and that game was the climax.

Elmore was a New Yorker with wide-ranging interests—he was the student council president at Power Memorial High School and wanted to get the student body involved in the social-justice causes of the late 1960s. UCLA recruited him, but as he said, “I wasn’t going to follow him again”—“him” being fellow Power Memorial product Lew Alcindor, later Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. His mother urged him to attend Princeton, but Elmore grew up watching the ACC Game of the Week on TV and wanted to play in that league. He also took a recruiting visit to the Duke Blue Devils, but chose Maryland because it was a little farther north and Elmore connected with assistant coach George Raveling, the first Black coach in the ACC.

Burleson, from rural North Carolina, was both a tall man and a tall tale—he was measured at a shade taller than 7'2" when he made the 1972 U.S. Olympic team, but was always listed as 7'4" at NC State. That was a publicity scheme hatched so that the Wolfpack could declare they had the tallest player in basketball, and Burleson said it annoyed him. (The school purposefully gave Burleson the No. 24 jersey and the 5'7" Towe No. 25, so that when the team lined up before games the difference in height would be all the more glaring.) Burleson turned down North Carolina—despite his assertion that “Carolina offered me money.” He was the cornerstone of the group that would tilt the balance of power in the state toward Raleigh, if only for a short while.

Elmore and Maryland won the first two meetings in 1971–72. But then NC State and Burleson turned the tide by winning six straight—defeating the Terrapins in the ACC tournament in both 1973 and ’74. The average margin of victory in those six straight Wolfpack wins was just 4.7 points.

Lane Stewart/Sports Illustrated

But even after losing in the ’73 league tourney, Maryland received the ACC’s NCAA tournament bid. That’s because NC State was on probation for violations committed recruiting Thompson, the transcendent talent from Shelby, N.C. (Burleson said all of the coaches in the state tried to keep Thompson’s high school exploits under wraps because they feared John Wooden coming in from California to land him at UCLA. “David was the greatest player of our generation,” he says.) In the end, the skywalking small forward choosing NC State was the piece the Wolfpack needed—even if it cost them in 1973.

They went 27–0 that season but had to watch the Terps go to the NCAAs and the UCLA Bruins extend their national championship streak to seven straight. “We were well motivated [for the 1973–74 season],” Burleson says.

Just three games into that season, however, the No. 2 Wolfpack were rocked by No. 1 UCLA, 84-66, in St. Louis. But that was the only loss NC State suffered in the regular season, rolling into the ACC tourney 24–1 and ranked No. 1 after the Bruins’ 88-game winning streak had been snapped in January by the Notre Dame Fighting Irish. The Pack easily dispatched Virginia to reach the final, but Maryland had a surprisingly easy time whipping North Carolina by 20 points on its side of the bracket.

“It kind of made you sick, seeing them play so good against Carolina,” Towe says. “They were really good.”

Before the tournament, Burleson was shocked and angry when Elmore was named the ACC’s first-team all-league center. Burleson figured his status as the first-ever, three-time all-ACC player was assured. When Elmore got the nod—and made a comment to the media pointed at Burleson—the NC State staff had its final piece of motivation. Assistant coach Eddie Biedenbach brought the clipping to Burleson at his locker to read it, then posted it on the bulletin board that was right nearby. Burleson had to look at the clipping every time he entered or exited the locker room.

Maryland had been torched in the previous five losses by Thompson, so Driesell shaded his defense toward slowing him down with extra defenders, which helped free up Burleson. Brimming with energy for that title game, Burleson was on fire—arcing in hook shots, making turnaround jumpers and scoring at will. He finished with 38 points and 13 rebounds, outscoring Elmore by 20 and prompting Driesell to seek him out after the game.

“Son,” Driesell told Burleson, “that’s the greatest game I’ve seen a big man play.”

Elmore acknowledges his rival’s performance as well: “That time, David wasn’t the difference. Tom Burleson was the difference.”

Others from the Maryland side were less gracious. Lucas’s comment in the papers the day after the game: “There were some people who played well who won’t ever play that well again.”

Truth be told, the Terrapins reserved their primary complaints for the officiating. Free throws were 26–8 in favor of the Wolfpack, a statistic that has been burned into Maryland basketball lore.

“I’m not saying it as a sore-loser thing,” Elmore says. “But they put them on the line a lot. Playing in Greensboro, the big four [North Carolina, NC State, Duke and Wake Forest] seemed to come out on top.”

That was the persistent complaint from the ACC schools outside of the state of North Carolina. For decades, the tournament was always in Carolina, and the Tobacco Road schools dominated. From 1954–75, every tourney was played in either Raleigh, Greensboro or Charlotte, and only one of them was won by a non–North Carolina school (South Carolina in 1971). When the tourney finally moved elsewhere, to Landover, Md., in ’76, Virginia won its first title.

Lane Stewart/Sports Illustrated

But in addition to the home-state advantage and a 7-footer playing the game of his life, there was one more key factor in NC State’s favor at game’s end: tiny Monte Towe.

Trailing 100-99 in overtime, Towe hooked a pass through the Maryland zone to Phil Spence for the go-ahead basket. “Phil was just always hanging around the basket,” Towe says. “And he always seemed to be open.”

A Maryland turnover with about 20 seconds left put the Terps on the brink. They fouled Towe with six seconds remaining, sending him to the line for a one-and-one to either ice it or leave the outcome up for grabs.

Towe was ready for this moment. He’d overcome being short his entire athletic career growing up in Converse, Ind., and came to NC State as both a point guard and a varsity second baseman. Playing alongside Thompson for four years—one on the freshman team and three on the varsity—Towe is credited with inventing the alley-oop. He perfected lobbing the ball toward the rim for Thompson to finish, even though dunking was not allowed then.

But with six seconds left and an NCAA berth on the line, Towe was all by himself on the foul line.

“I put myself in those situations in Converse, shooting at the hoop over the garage,” he says. “Snow on the ground, gloves on sometimes, practicing game-winning free throws before going in for the evening.”

Towe never took long at the line, and he didn’t that night, either. He made both foul shots, and NC State was on its way to the NCAAs after what was celebrated as the greatest college basketball game yet played. Maryland was on its way home, season over, a third straight loss in the ACC tournament final in the book—this one the most painful yet.

That can stay with a man. Even 50 years later.

“The primary—and primal—emotion is that we didn’t win,” Elmore says. “And that lasts a lifetime.”