If your household is like most American families, then today you likely will all be sitting down with family and friends to a traditional Thanksgiving turkey dinner during the mid-to-late afternoon hours. Then as darkness falls, some will probably migrate into the living room to catch some football or other holiday fare on television.

But if you have a large gathering of family and friends at your home — and if your skies are mainly clear — why not invite everyone outside to gaze at the evening sky? If you have binoculars, or better yet, a telescope, you just might end up turning this into a memorable family tradition of its own.

Throughout the summer and into early fall we were starving for a view of bright and accessible planets. But now, at Thanksgiving time, we have a feast. There are no fewer than three bright planets shining prominently during the early evening hours: Saturn, Jupiter and Venus.

Three bright planets

Want to see Venus, Jupiter or Saturn up close? The Celestron NexStar 4SE is ideal for beginners wanting quality, reliable and quick views of celestial objects. For a more in-depth look at our Celestron NexStar 4SE review.

As darkness falls, Jupiter, nearing its biggest and brightest for 2024 rises north of due east and remains on display virtually all night long.

Even more brilliant, on the opposite side of the sky, is Venus, which gets higher each night and remains visible in the southwest for up to three hours after sunset by the end of November.

Also in excellent position is Saturn, shining with a sedate, yellow-white glow and at nightfall appears roughly midway between the other two planets, about two-fifths up in the south-southwest sky.

Venus is the first to come into view in the southwest right around sunset. During November this lustrous Evening Star has made a significant climb for observers at mid-northern latitudes. A telescope shows the dazzling disk of Venus about three-quarters illuminated and it is still rather small.

Although Venus is brighter, Saturn and Jupiter in every other way are superior to Venus for observers. With a telescope magnifying 30-power, the famous rings of Saturn begin to be visible. If you have a 4-inch telescope, a 100-power eyepiece will readily bring Saturn's rings into view; always a delight for first-timers who have never seen the rings for themselves.

Meanwhile, far brighter than Saturn and standing about 10 degrees above the east-northeast horizon about 90 minutes after sunset will be Jupiter, appearing like a dazzling, silvery-white, non-twinkling star. Since your clenched fist held at arm's length measures roughly 10 degrees, Jupiter will be about "one fist" above the horizon as the last trace of twilight glow disappears on Thanksgiving and will ascend higher into the sky as the evening wears on.

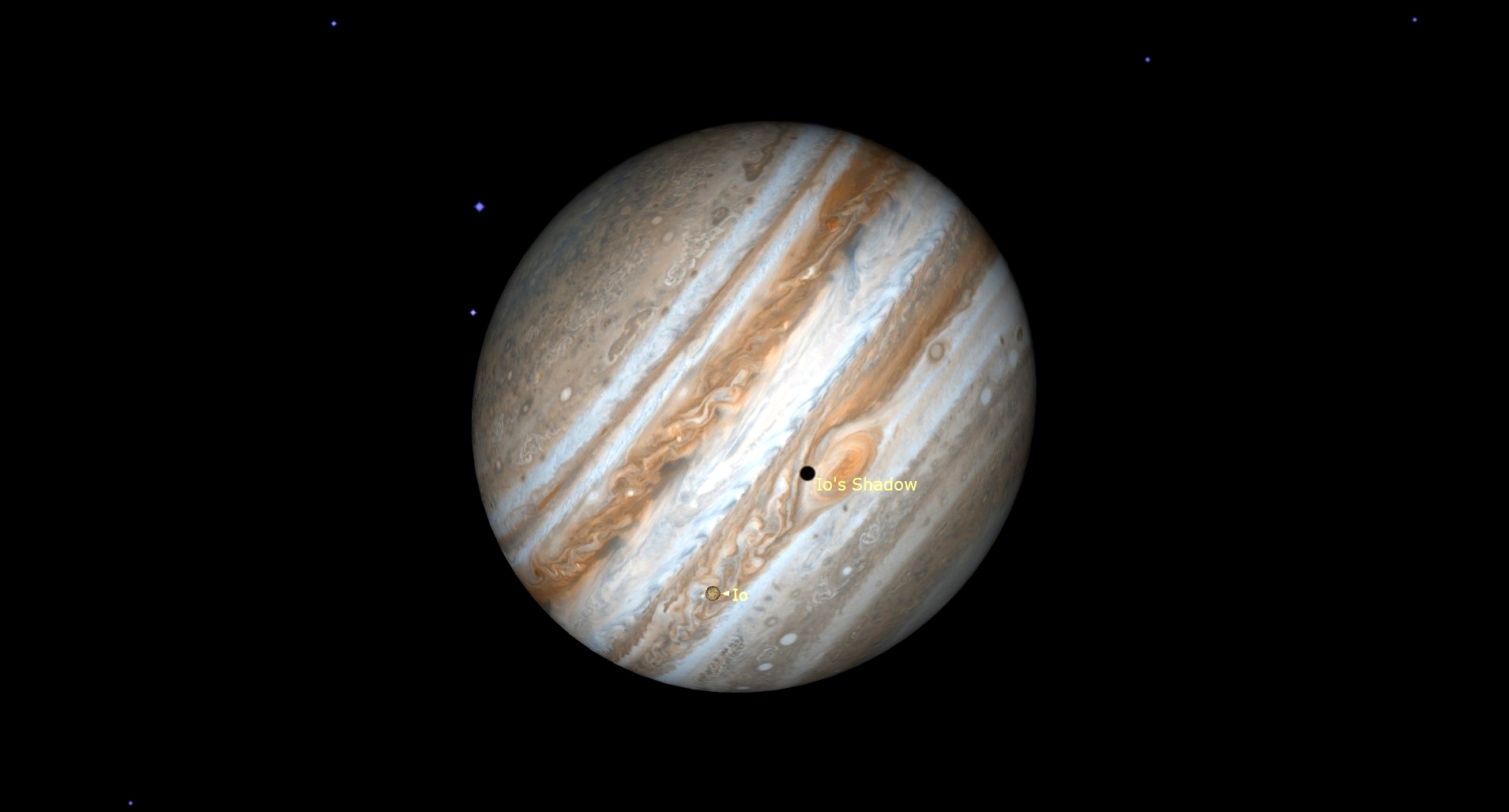

Steadily-held binoculars will provide a glimpse of the four big Galilean satellites, first glimpsed by Galileo in 1610. A telescope will easily show the disk of the biggest planet in our solar system – 11 times larger than our Earth – with all four moons in view, three on the east (left) side of the big planet: Callisto, Ganymede and Europa, and Io on the west (right) side on this holiday night.

If you want to try your hand at capturing events like these on camera, we can help you find whatever you need. Check out our guides on how to photograph the moon or how to photograph the planets to learn more about basic astrophotography skills. And if you need optical equipment or photography gear, consider our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Stars of late autumn

If we concentrate on the stars and constellations, it is interesting to note that many of the star groups and rich Milky Way fields of summer evenings are still very much evident in the western part of the sky, while the brilliant yellow star Capella ascending in the northeast is a promise of even more dazzling luminaries to come. For in just another few weeks, Orion and his retinue will be dominating our winter skies.

Still very well placed high in the west is the Summer Triangle, a roughly isosceles figure composed of the stars Vega, Altair and Deneb. As we move deeper into the autumn season and the evenings grow all the chillier, this configuration sinks lower and lower in the west. If you have binoculars, invite family and friends to use them to sweep among the splendid star fields of the Summer Triangle. They may very well share Galileo’s awe when more than four centuries ago he first turned his telescope on the myriads of faint stars that compose our Milky Way.

Looking high in the south-southeast – almost overhead – are the four bright stars that compose the Great Square of Pegasus, a landmark of the autumn sky. And if you have a clear view of the northern horizon, it is there where you will find the familiar Big Dipper, looking abnormally large due to the "moon illusion" which makes both the sun and the moon and even star patterns like the Dipper appear larger-than-normal when they are situated near to the horizon. Meanwhile, the striking zig-zag row of five bright stars forming the ”M” of Cassiopeia, the Queen soars high above the Dipper in the north.

Looking back in time

The very first Thanksgiving is said to have taken place in the year 1621. We see many stars by light that started its immense journey before our country was born. Are there any stars that are around 400 light years away?

Because of the difficulty in measuring parallaxes (distant objects' changing positions when viewed from Earth), astronomers cannot determine such distances with an accuracy of one light-year. However, the 2024 "Observer’s Handbook" of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, in its table of 288 brightest stars, lists two that are above the horizon on November evenings that are 400 light-years away: Third-magnitude Algenib, the star in the lower left corner of the Great Square of Pegasus, and second-magnitude Almach, at the end of the chain of stars marking the constellation of Andromeda, the princess.

If you see either of these stars on your next clear night, keep in mind that you are looking at light that started on its journey to Earth about the same time that the first pilgrims were arriving in what we now call the state of Massachusetts.

Here at Space.com, we like to wish a very happy and safe Thanksgiving to all, and of course, clear skies!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications.