Recently, South Africans were told about an extraordinary escape story – they learnt that a convicted rapist, Thabo Bester, had been at large for a year after he’d escaped from a privately-run maximum security prison. In May 2022 the Department of Correctional services reported that he had burnt to death in his cell. But a forensic report – which prison authorities only released recently after dogged reporting by journalists at the news outlet GroundUp, showed that the body wasn’t his.

Bester was re-arrested in Tanzania over the Easter weekend and arrests have been made in connection with his escape.

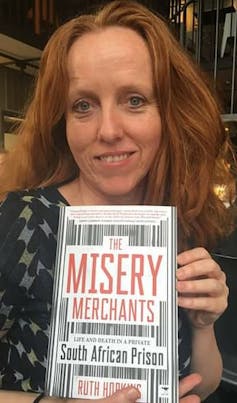

The story has raised questions about the management of privately-run institutions such as the Mangaung Maximum Security Prison in Bloemfontein from which Bester escaped. Ruth Hopkins is an investigative journalist who recently wrote a book – The Misery Merchants: Life and Death in a Private South African Prison – about G4S, a British multinational private security company running the Mangaung prison. Between 2012 and 2018 she worked for the Wits Justice Project which investigates wrongful convictions, lengthy remand detentions, police brutality and other criminal justice issues. Conflict criminologist Casper Lötter asked for her insights into Bester’s escape.

What does the escape illustrate about your investigation?

Based on my findings I believe Bester’s escape illustrates the fact that there is corrupt collusion between Department of Correctional Services, G4S and the South African Police Service.

Bester’s case reminded me of Isaac Nelani, an inmate at the Mangaung prison, who died in 2014. The pathologist, Gene Book, found Nelani had bruising on the back of his head, which pointed to ‘blunt force’ and therefore he deemed the death ‘suspicious’.

But the South African Police Service, the Department of Correctional Services and G4S worked together to cover up this probable murder. In 2015 I wrote a story for the South African newspaper the Mail & Guardian about Nelani’s death. The department of Correctional Services filed a complaint about the article with the Press ombudsman. The ombudsman ruled in my favour.

The department’s action clearly indicated that it was actively protecting the multinational, because it challenged me on a case that primarily implicated G4S.

This collusion ruled out any accountability.

In my view the same collusion made the Bester escape possible.

On May 20 2022 journalist Mzilikazi Wa Afrika wrote to the department notifying them of Thabo Bester’s brazen escape. But it failed to take any action.

The department also knew about Nelani’s death, because all deaths in prison have to be reported to the department. It would therefore have been aware of the pathologist’s report.

As I establish in my book, it also knew about widespread torture through electroshocking, forced medication with anti-psychotic drugs, serious assaults, riots, hostage takings and suspicious deaths.

Yet there was no accountability. G4S retains the contract.

The 25-year contract for Mangaung prison was signed in 2000. It is due to expire in 2026.

What were the biggest problems you unearthed at the prison?

The Emergency Security Team, known as the Ninjas, used their electrified shields as a torture instrument and regularly electroshocked prisoners, for minor transgressions such as complaining about the quality of food or the lack of blankets. In practice electroshocking was used randomly and rampantly.

Forced injections with anti-psychotic drugs were also a widely used method of crowd control. CCTV video footage from within the prison was leaked to me and contained evidence of prisoner Bheki Dlamini being forced to undergo an injection with the anti-psychotic drugs Etomine. Dlamini had no record of mental illness.

The number of suspicious deaths in Mangaung prison that I came across were another issue that was incredibly concerning. In 2015 the then national commissioner of correctional services Zach Modise announced that the department would appoint a task team to look into unnatural deaths at Mangaung prison. The task team was never heard of again.

The treatment of G4S employees is another egregious problem. For years, guards petitioned the prison management, demanding improved safety and security measures. Many suffered terrible violence at the hands of inmates.

For example, the guards wanted the ceramic toilet pots to be replaced with cast iron ones because the ceramic pots were smashed and the shards used as weapons to stab warders. The company denied the allegations. It never offered any improvements.

As I have written, the practice of making money from punishment has grown in South Africa. What’s the situation when it comes to privatisation?

Only two of South Africa’s prisons are run by private companies. Mangaung is run by G4S and Kutama Sinthumule in Louis Trichardt, Limpopo, is run by the US-based GEO Group.

No other prisons have been privatised and it looks as though it’s unlikely to happen.

When I was working for the Wits Justice Project, I visited and wrote about approximately 20 state-run prisons in the country. Torture and violence are prevalent in these institutions too. But my findings in researching the book showed that it was more prolific in Mangaung prison.

Ruth Hopkins is an editor at Corpwatch and the founder of the Private Security Network (PSN). Private Security Network is part of Corpwatch.

Casper Lӧtter does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.