Nick Kyrgios walks right up to the line. After grabbing a towel, he trades it for a tennis ball. He bounces it just once, an expression of his “crazy impatient” (his term) nature and his let’s-get-on-with-it-already mode of being. He starts his serving motion, a bit of muscle memory, both intricate and blissfully simple. A rock-back. A toss. A torque of his 6'4" frame. And then the liveliest arm in tennis cracking the ball.

And for a moment, anyway, it all fades. The pressure. The fierce and divergent opinions he triggers. More gravely, the domestic violence allegation, which has added a darkness to all the usual storm clouds.

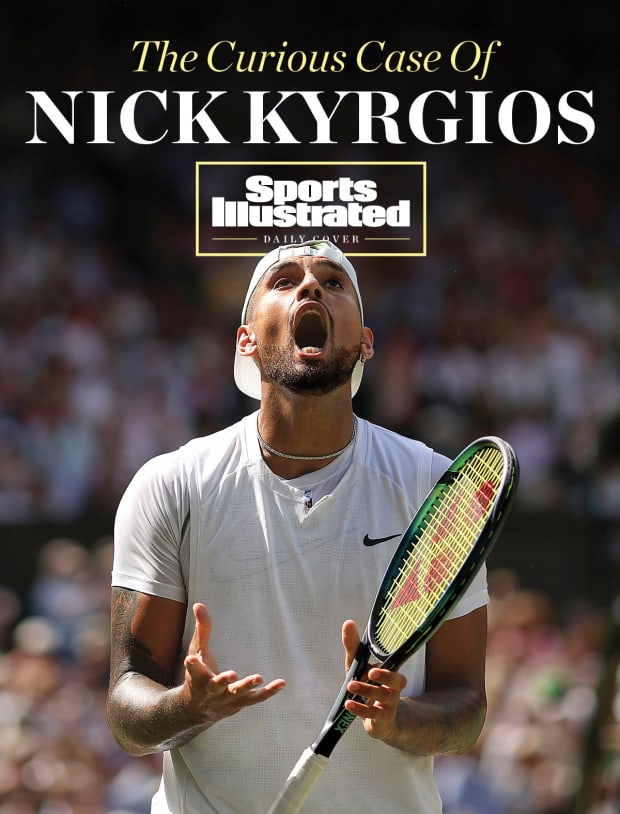

It was the early rounds of the Citi Open in Washington, D.C., and Kyrgios, tennis’ enfant terrible … no, wait, its bold disruptor …. its deplorable bad boy …. or, no, its charismatic clown prince … was a point away from victory over Marcos Giron, a grinding UCLA alum ranked No. 53, ironically 10 spots higher than the star on the other side of the net.

Julian Finney/Getty Images

Kyrgios paused for a moment. He was wearing a casual look, multiple earrings, a backward ballcap and a shirt that would make Joseph’s technicolor dreamcoat look subdued. (The red Air Jordans, and collection of NBA jerseys he’s keen to wear when not playing, rested comfortably in his locker.). He had spent the evening bringing his casual brilliance to bear, whistling as he sent the ball whistling past Giron. This point was no different.

Which is how it’s been so far this summer. At age 27, Kyrgios has added a new descriptor to go with the innumerable others applied to him over the years. He is finally downloading his vast talent into success, avoiding (narrowly; not always) his instincts to self-sabotage, benefitting from a bit of luck and fulfilling his potential. And suddenly, it’s as if he updated his tennis LinkedIn profile, changing “talented underachiever” to “winner,” if not yet “champion.”

This run began in June, when Kyrgios got onto the grass, a surface that accentuates his power, and makes for the kind of short points that mask his questionable durability. He came to Wimbledon in his usual role as “dark horse,” unseeded and ranked behind 62 other players, a reflection of his play-when-I-feel-like-it mode of being. Then, over two weeks, Kyrgios did what many either thought was never possible or thought was inevitable. What they hoped would finally happen … or thought would never happen.

He not only reached the final before capitulating to Novak Djokovic, no shame in that: Kyrgios dominated. Even the prospect of Djokovic—a magnetizing, polarizing figure in his own right—winning his seventh title at the All England Club and 21st Major overall was reduced to a sideshow. For two weeks, Wimbledon doubled as The Kyrgios Show. Which was great for tennis. Or terrible.

For going on a decade now, Kyrgios has cleaved the Republic of Tennis, creating two sides, roughly equal in proportion, that may as well be divided by a net. He is either the box-office shotmaker, the candid and charismatic and compellingly volatile McEnroe-meets-Draymond bundle of unpredictability that will bring freshness and electricity, bring in the kids and bring change to a tradition-choked sport.

Or he is an unhinged narcissistic brat (or something still darker), who competes like a coward and respects nothing—not his opponents, not his sport, not his predecessors, and not least his own talents.

Or both.

It’s complicated.

Even this summer, Kyrgios has done little to change impressions or clear up ambiguity or change the gavel of public opinion. Both sides have heaps of evidence, new and old, to support their position.

The son of George (a Greek-born house painter) and Nill (a Malaysian-born computer engineer) Kyrgios, Nick was the youngest of three kids. He grew up in Canberra, Australia’s capital, a landlocked swatch of city roughly halfway between Melbourne and Sydney. He began playing tennis at a young age, and somehow managed to be both intensely competitive and wholly unserious.

George recalls that “even way back then” his son was never much for practice. The kid also devoted heroic amounts of time to video games. And he himself has surmised that his physique and his asthma meant that he had to come up with creative ways to win. Lord knows, he wasn’t going to outlast opponents in too many battles of attrition.

“We thought he was hitting trick shots,” says Thanasi Kokkinakis, Kyrgios’s pal and doubles partner and contemporary since their days on the Australian junior circuit. But no, Kyrgios doing strange things with the ball, not for show, but because his strange style helped him win points.

Today, there is one sliver of common ground when it comes to Kyrgios: We can all agree he is dripping with tennis talent. He might come armed with the most effective serve in tennis, using his point-starting to devastating effect—both as a sword to send balls scything through the grass and as a shield, protecting him during tricky moments. Apart from the sheer power, Kyrgios (predictably) has few predictable patterns. Sometimes it’s a cutter outside wide; other times a body serve. Even Djokovic, maybe the most gifted returner ever to grip a racket, marvels at the Kyrgios serve: “Even when you guess right, it can feel like you guessed wrong.”

Geoff Burke/USA TODAY Sports

But there have been other titanic servers, past and present, who haven’t inspired a fraction of the awe that the Australian can. It’s once the ball is in play that Kyrgios really shows off his wand work. He can win rallies by swatting winners deep in the court, especially from the forehand side. He can also win by slicing and defending and summoning angles and deploying drop shots. Even his trick shots and spin-drizzled underarm serves, sometimes struck, he admits, less out of strategy than boredom, reveal unholy levels of touch.

“He is literally a genius when it comes to feel, tactics and hitting the right shot at the right time,” says Mats Wilander, the Hall of Fame player, now an astute commentator. “You have just got to shut that out and put a blindfold on. Do what you can do as a player and don’t worry about what goes on, on the other side.”

Ah, yes, the other stuff. Kyrgios goes for the social norms of tennis the way Boris Johnson goes for a comb and hairspray. Kyrgios has long been the lone top-100 player without a coach, a choice he made years ago. Asked about adding an aide-de-camp, he said, “I don’t want to put anyone through that.” (Meanwhile his former coach, Josh Eagle, told reporters: “I don’t think he is coachable. He’s too far down the track in doing [things] his own way. He wouldn’t listen to anyone.”)

When his lesser angels take over, he is simply indefensible. He spits and swears and throws tantrums. In one of his lowest moments, he informed an opponent mid-match that Kokkinakis had slept with the opponent’s girlfriend. When his better angels take over, he is charm personified. He signs more autographs and sits for more selfies than any 10 players combined. One of his more endearing bits entails consulting fans in the stands and asking them where he ought to serve next.

He strenuously avoids the cautious and clichés. Earlier this year, Kyrgios used social media to speak openly about his mental health challenges and suicidal thoughts. He’s the same way with the media. Ask him a question, you get a straight answer. If you don’t like it, that’s a you problem.

Earlier this summer, I asked Kyrgios whether his obsessive fandom for the Boston Celtics had any carryover to his tennis. He started laughing before speaking and said this: “I’ve literally thrown tennis matches if they’ve lost in like, double overtime. If someone plays me and they know the Celtics have lost, that’s [their] chance. That is for sure your best chance [to beat me], to play me on that day.” If this were any other player, an admission of throwing a match, or “tanking” in tennis parlance—a cardinal sin and fineable offense—would make for A1 news. But with Kyrgios, it’s just Nick being Nick.

Matthew Stockman/Getty Images

From the jump, Kyrgios and his sui generis pathbreaking did not endear him to the tennis establishment. Perhaps tracing deeper cultural fissures, the old-school Aussies have often been particularly critical of the new star who doesn’t play, act or look like them. Born within a year of Kyrgios, Ash Barty, the recently retired women’s champion, is invariably described as “fair dinkum.” Kyrgios is seen as other and lesser.

Before the Wimbledon final, he was tossed an innocuous question about his role in Australia and its tennis lineage. Kyrgios used the occasion to talk about how wounded he feels by his compatriots. “As for the greats of Australian tennis, they haven’t always been the nicest to me personally. They haven’t always been supportive. They haven’t been supportive these two weeks. So it’s hard for me to kind of read things that they say about me. … It’s weird they just have, like, a sick obsession with tearing me down for some reason. I just don’t know whether they don’t like me or they’re afraid. I don’t know. I don’t know what it is. But it sucks.”

I asked Kyrgios why he continues to be so stung by criticism. His response: “I was an overweight kid when I was young. I had a lot of coaches and teachers telling me I wasn’t going to be good. I’ve dealt with the same criticism, throughout Australia, racism, everything. I still have a big chip on my shoulder. It stings me. It doesn’t really sting me now. But I don’t forget it. So now when I’m up, I won’t let you forget about it. … I just need to channel it in the right way. I definitely need thick skin, because I deal with a lot.”

It’s not so much that Kyrgios is a riddle as he is a contradiction. He speaks out often against bullying—slagging, in Aussie speak—and is quick to pronounce himself a victim. At the same time, Kyrgios berates officials more often and more viciously than any other player, including an unfortunate habit of using the word “r----d.” Especially in and after defeat, he is not beyond spitting, swearing and hurling equipment. At Wimbledon, he may have been the runner-up, but he was the tournament “winner” in fines accumulated.

He takes great pride in his popularity among colleagues, even among players who have much to lose from an association gone bad. Naomi Osaka—known as much for her social justice and mental health advocacy as for her tennis—recently left IMG to open her own management agency. Her first client? Kyrgios, who frequently breaks the code of the locker room and can treat opponents in ways that can verge on cruel.

ADRIAN DENNIS/AFP/Getty Images

In the third round of Wimbledon, Kyrgios met No. 4 Stefanos Tsitsipas. Other than sharing Greek heritage, Kyrgios and Tsitsipas are studies in stark contrast. A sensitive, contemplative soul, Tsitsipas is known for social media postings that often quote lines of philosophy or musings. (He once noted “It’s amazing how many different sounds you can hear while walking in NYC” Kyrgios, who often speaks out against the toxicity of social media, saw this and responded simply: “Da fuq.”)

What followed was tennis masquerading as a UFC fight. Kyrgios goaded Tsitsipas, who didn’t so much take the bait as devour it whole. Clearly rattled by what he called “the circus,” Tsitsipas wasted points trying to drill Kyrgios with shots; he once looked to be on the verge of crying; in frustration he rifled a ball into the crowd, leading to the strange sight of Kyrgios demanding an opponent be defaulted for ill behavior. After losing in four sets, Tsitsipas called Kyrgios “a bully,” noting, “He has some good traits in his character, but he also has a very evil side to him, which if it’s exposed, it can really do a lot of harm and bad to the people around him.”

This observation took on extra valence three days later, when Australian authorities released a statement that Kyrgios “had been summonsed to face a common assault charge” in relation to an incident in Canberra in January 2021 for an alleged “domestic violent incident” with his girlfriend at the time. A court date in Canberra was set for Aug. 23 and was then adjourned to Oct. 4. (Given a chance to address the allegations, Kyrgios said: “Obviously I have a lot of thoughts, a lot of things I want to say, kind of my side about it. Obviously I’ve been advised by my lawyers that I’m unable to say anything at this time.”)

Then there is Kyrgios’s relationship with the sport, one he readily characterizes as “love-hate.” In one breath, he says, “I want to prove I’m one of the most elite.” In another, he volunteers he wished the sports gods had tapped him with basketball talent, not tennis talent.

There may be something embedded in that. … If you really want to see Kyrgios light up, place him in a team environment. At the Davis Cup and Laver Cup, he doesn’t cease smiling. The highlight of his career so far is perhaps his winning the 2022 Australian Open Doubles title with Kokkinakis. (Kyrgios being Kyrgios, that triumph included a near fight after Kyrgios drilled an opponent with a ball and called him “soft.”)

It takes something less than a licensed sport psychologist to suggest that Kyrgios bristles at the pressure of an individual sport where the entire weight of expectation falls on him and him only. All of his proud apathy and “I don’t apply myself” bravado is a defense mechanism, something akin to the kid in school who brags about getting a “B” without studying.

Whether he cares more than he lets on, or whether his talent can simply prevail, Kyrgios is getting some of the best grades of his career this summer. And, for a variety of reasons, everyone seems to be watching.

The U.S. Open is next. Tennis can, and will, continue to process Kyrgios, weigh in, and work through the moral ambiguity of it all. Is this the future of the sport, especially as the Federer-Nadal-Djokovic troika get on in years, now 41, 36, and 35, respectively? Can the sport accommodate such an outlier? How does one even entertain this exercise while a domestic violence charge pends in the court?

Finally, it is up to Kyrgios to write the author the next chapter, either evolving or regressing. He’ll be the one to answer the question: Will the clown become a king? Or will the palace become a circus?