Today the All England Lawn Tennis Club, hosts of the famous Wimbledon Championships, pledges to be diverse and inclusive. But in 1971 an 18-year-old university student, Hoosen Bobat from Durban, was excluded from achieving his dream of becoming the first black South African to play in the Wimbledon men’s junior tournament. This was due to apartheid, and the collusion of the all-white tennis union in South Africa and the International Lawn Tennis Federation, with Wimbledon toeing the line.

I tell Bobat’s story in the new book Tennis, Apartheid and Social Justice. I am a scholar who has published numerous books and papers on the histories of black exclusion and organised black resistance during apartheid, and on social justice and transformation.

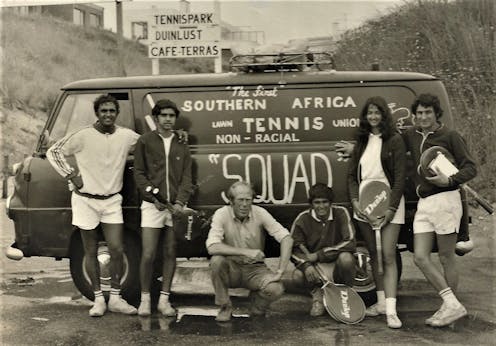

My book documents the historic 1971 first international tour by a squad of black South Africans who played tennis under the auspices of the non-racial Southern African Lawn Tennis Union.

In 1973, the union was a founding affiliate of the South African Council on Sport, which popularised the slogan

No normal sport in an abnormal society.

In the context of apartheid, this must be contrasted with tennis played by white South Africans under the racially exclusively white tennis union.

The 1971 touring players were dubbed the “Dhiraj squad” after tennis champion Jasmat Dhiraj, a school teacher. The other five were Hira Dhiraj, Alwyn Solomon, Oscar Woodman, Cavan Bergman and Bobat.

The union’s goals were for its most promising players to compete in tournaments in Europe irrespective of “race” and nationality, to improve their games and be ambassadors for upholding equity and human dignity in sport.

Read more: The South African Council on Sport at 50: the fight for sports development is still relevant today

I wrote the book because I believe important social justice issues arose from the tour. At a minimum, a public apology is due from the international tennis body and Wimbledon to the non-racial sport community, the 1971 tour players and Bobat.

I also thought it was important to tell the story while most of those who lived through it were were still with us. And the book was also an opportunity to focus on “ordinary” people, on unsung heroes, on their tribulations and triumphs. A focus on everyday histories rather than on dramatic events and on elites.

The issues

In the book I cover three issues.

Firstly, I place the tour within the political, social and sporting conditions under apartheid. In 1971 South Africa was a racist, segregated and repressive society, based on white supremacy and privilege and black subjugation. Black people were denied proper sports facilities, coaching and opportunities to excel, could not belong to the same clubs as whites or compete in competitions with or against white players. Considered subjects, not citizens, they couldn’t represent South Africa in sport. Sport under apartheid was a killing field of ambitions and dreams.

Secondly, it records the players. The tournaments they participated in, their performances and challenges, the tour’s impact on them, the lessons learnt and their lives and tennis accomplishments after 1971.

Thirdly, the book demonstrates the collusion between the International Lawn Tennis Federation and the white South African tennis body. That collusion, and the action of the All England Lawn Tennis Club, prevented Bobat from becoming the first black South African to play in the junior Wimbledon championships.

The arguments

I make five main arguments.

One is that, since democracy in 1994, there has been no fitting recognition, symbolic or material, of outstanding apartheid-era non-racial tennis players. Nor has there been appropriate restitution and reparation of any kind.

A second argument is that apartheid’s legacy continues to profoundly affect and shape tennis today. A walk around the affluent white town of Stellenbosch in the Western Cape province and a black township like KwaMashu near Durban reveals the stark differences in terms of tennis courts, coaching and the like.

Third, probably less tennis is played today in black schools and communities than before democracy. Certainly, there is less self-organisation of the kind that harnessed limited economic and social capital in black communities to ensure non-racial tennis.

Fourth, as in other areas of South African society, there has been much talk about “transformation” but little substantive transformation in tennis.

Fifth, there should have been a Truth and Reconciliation Commission for sport that laid bare apartheid sports crimes, the perpetrators and collaborators, and forged agreement on reparations and transformation.

The collaborators included big business and the media. With the support of the South African sugar industry, the tennis Sugar Circuit became the “breeding ground for world ranked (white South African) players”. The sugar industry was built on the blood and sweat of Indian indentured labour and black labour more generally.

Yet, sugar big business did little to support black players. The commercial media linked to big business were also complicit, devoting print copy and airtime principally to white sports.

Class, racism and patriarchy

Opportunities in tennis were profoundly shaped by class, racism, patriarchy and other factors.

The players in the 1971 tour were classified “Coloured” or “Indian”. There were no “Black” South African players chosen because of a debatable notion of “merit” used by the Southern African Lawn Tennis Union.

And the tour was an exclusively male affair even though there were outstanding women tennis players and well-established women’s tournaments. Charmaine Williams joined the tour at her own expense.

In my study I identify how non-racial tennis officials in South Africa exemplified dominant patriarchal attitudes and didn’t take gender inclusion seriously. This would remain an issue in the South African Council on Sport of the 1970s and 1980s.

Jasmat Dhiraj told me that he had to “overcome inhibitions and complexes” on tour. Bobat states that they

had to overcome the so-called inferiority complex of playing against white tennis players.

Truth and justice

Former South African president and liberation leader Nelson Mandela commented in 1995:

We can now deal with our past, establish the truth which has so long been denied us, and lay the basis for genuine reconciliation. Only the truth can put the past to rest.

But, in my view, instead of dealing with our past South Africans are letting it fester, failing to see that genuine reconciliation cannot be achieved by ignoring the injustices and pain of the past.

Saleem Badat receives funding from the National Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.