We're digging into the PC Gamer archives to publish pieces from years gone by. This article was originally published in PC Gamer issue 182, Christmas 2007.

Back in the summer of 1994 everyone was getting excited about Doom 2. Everyone was wrong. The only game that mattered was System Shock.

It was a defining game for me, and for the handful of others who played it. Doom 2 was fun, but System Shock was changing our perceptions about what gaming could be. It was the big step forward from Ultima Underworld, with a physics system, realistic textured environments, complex AI, and a towering, terrifying story of isolation and persecution aboard a malevolent space station. This was the first showdown with megalomaniac computer SHODAN, and it's something I'll never forget.

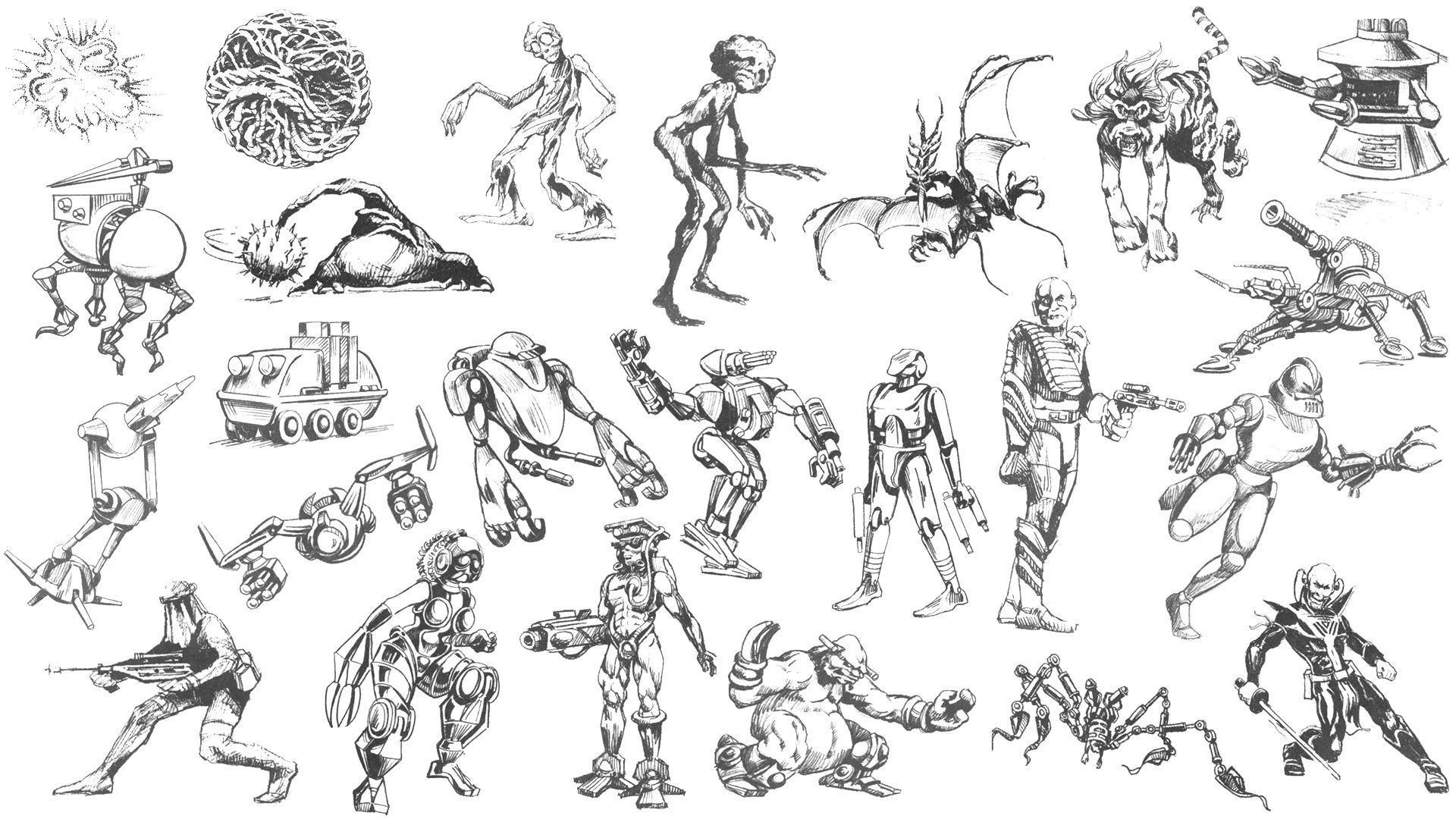

Some gamers were confused and disappointed by the low-key opening. The squalid medical bays seemed rather lacklustre compared to Doom 2's gothic techno-fortresses, and beating a haywire service bucket to death with a stick didn't seem quite as thrilling as hitting the high notes with a point-blank shotgun blast. There might not have been a great sense of urgency in the opening hours, but this wasn't about the big adrenal release. System Shock was the slow build, the growing realisation of the scale of disaster and horror. You really were in the midst of something utterly terrible.

Even though System Shock never had the capacity to deliver a living, chat-enabling NPC, you almost always expected to meet one. Indeed, everything else about this game was so spectacularly ahead of the curve that it seemed inevitable that there would be someone just around the corner—2004's Alyx Vance, or something. Indeed, you even started to get messages from just such a character. And though you never did meet—could never have met—her story was convincing enough and affecting enough to have you cursing the malign power of SHODAN and her robots. There was worse to come.

Although you never see another living person, they're brought to life via their journals and diary entries. This is what inspired BioShock's own series of voice-recordings, and, for those people who were lucky enough to buy the CD rather than the floppy disk version of System Shock, they were revelatory. Competent acting with CD-quality reproduction: this was a great leap forward for the time, and brought game audio into the modern age.

Even with its graphically crude presentation, System Shock delivered the most believable, detailed environments we'd ever seen. Each of them was perfectly pitched—the great air-locks of the spaceport section, the clunky jungles of the bio-spheres, and the surprising elegance of the executive suites. More than BioShock's Rapture, the System Shock space station gave a strong impression of being a working thing—a device for living in space.

The structure of the game emphasised this: you were back and forth madly between the various zones, trying desperately to break SHODAN's control and, ultimately, save both yourself and the planet full of people that the deadly station was cruising toward.

This was a story of escalation. You start off knocking over zombies and poking about in the trash of a ruined space station; soon you're exploring the innards of a supercomputer with destructive intent. You run a gamut of feeling, from bafflement to horror and revenge. And finally, there's the vertiginous sprint through the collapsing station, into the brainstem of the beast—into SHODAN. After years of playing FPS games that finish on a low, you might be forgiven for thinking there were no great FPS endings out there. System Shock tells us otherwise.

Crucially, SS made you feel vulnerable. This is not the story of the superhuman warrior of the Doom games, this is the tale of a human being. Sure, you can plug into the computers to play out cyberspace subgames, but you're still a person who can walk, lean, crawl, climb, fall, and die all too easily.

System Shock might lack graphical sparkle by today's standards, but its realism and humanity reached levels as high as any game has managed in the last couple of decades.

The interface seems crude now, mostly because it is devoid of mouselook. The visuals, too, are hard on modern eyes. But the powerful musculature of the beast remains: the story, with its perfect pacing and savage crescendo, still beats anything we can play today. If BioShock had retold System Shock's tale, beat for beat, it would probably have earned even higher scores.

The man we have to thank for it all was Doug Church. Truly, Church is one of the fathers of gaming. His vision of what was needed to create intelligent FPS games was what inspired Warren Spector to create Deus Ex, and Ken Levine to create BioShock. Without Church's insistent vision and profound grasp of the possibilities that gaming provided, we would not be living in the same gaming world today. Thanks Doug, I think you saved us all.