'We teach them humans are not friends, but foes," said Tanet Uttaraviset, an animal scientist at Nakhon Ratchasima Zoo, while opening the door of the nursery for young sarus cranes. Inside this leafy circular enclosure is a green puddle where his words echo the conflict between humans and tall waterbirds under threat of extinction.

"Outsiders are dangerous," he added.

In the old days, there was an abundance of cranes in fields and swamps. HRH Prince Damrong Rajanubhab visited cities in Nakhon Ratchasima between December 1905 and February 1906 and in his record Lan Nokkrarian (Crane Field), tens of thousands of cranes were building nests in Thung Makha. However, it was not long after that human encroachment endangered them.

Despite being raised in a secluded environment, these offspring are trained to survive the harsh world outside. Every year, a group of sarus cranes bids farewell to the breeding ground for Buri Ram. However, when the cages first opened, they did not leave. It was not until keepers caressed them that they mustered the courage to fly. In the blink of an eye, they were gone.

Unknown to laymen, they became extinct half-a-century ago. But in recent years, they have been rescued from a man-made apocalypse. Starting in 2011, a reintroduction programme has brought them home every year. Last month, the Zoological Park Organisation released 11 sarus cranes into the wetlands of the Huai Chorakhe Mak reservoir in Buri Ram. Currently, a total of 144 have been set free.

Tanet said the National Economic and Social Development Plan in 1961 increased demand for land and brought about environmental change. Since then, sarus cranes began to disappear and it was not until 1989 that the zoo received some from Cambodia. In 1992, they were listed under the Wild Animal Conservation and Protection Act.

"However, staff lacked expertise and had trouble breeding the original population of 27. We were clueless about their behaviour. In the past, foreign textbooks were the only source of knowledge and staff learned everything through trial and error. It took seven years to produce the first baby in 1997," he said.

Sarus cranes are a symbol of eternal love because they are monogamous, but this mating behaviour can make breeding difficult. Tanet said they lay only two eggs per year, which may not hatch. Sometimes, they peck and crush the eggs, so artificial insemination and egg incubation are used to increase the population.

"Artificial insemination is the delivery of sperm from a male to the reproductive tract of a female. Potential donors are massaged in preparation for giving semen," he said. "When it comes to incubation, a female can produce four to six eggs per year. However, we stopped when there were enough breeders because egg production overworks the reproductive system."

Tanet said sarus crane chicks are isolated from their parents within a week of birth to ensure that keepers can train them for the outside world. If they are independent, they will be released into nature. First, they must detach from the keepers and second, they must aggregate to increase their chance of survival. In nature, they leave their parents within one year.

"When they are seven to eight months old, we assess their independence. If they are still following us, they will be kept here for breeding. On the other hand, those who meet the requirements are transferred to Buri Ram where they are allowed to adapt to a new environment for three to four months. By the time they are released into nature, they are already one year old," he said.

"Staff used devices to track sarus cranes from 2011-2019 and when they gathered enough information, they stopped and asked locals to monitor them."

However, the challenge remains for breeders. In theory, life expectancy is 70 to 80 years. and since they have been raised since 1989, today's sarus cranes are in their 30s. Currently, there are 26 couples out of around 100. If their mate dies, others can replace them. However, the process of pairing is risky.

"Potential mates are placed near each other. If they show signs of attraction for three to four months, they will be paired. However, they can also end up hurting each other and we are still trying to understand the reasons. But it is has been theorised that they are not soul mates and could feel territorial," he said.

Not everybody agrees with the reintroduction programme because animals should originally live in the wild. However, Tanet said that if he lets nature take its own course, sarus cranes will be vulnerable to extinction. Intervention allows them to live longer because they receive food and proper care.

"You pay a heavy price for freedom," he said.

There are 15 species in the crane family. According to the International Crane Foundation, 11 of them are in danger of going extinct. The sarus crane is the tallest flying bird in the world. It stands 150-180cm tall and weighs between 5-9kg. When they were first reintroduced, the move was met with disapproval.

"At first, locals did not understand and feared they would destroy rice. But zoo officials assured that they eat small aquatic animals and do not cause damage to rice because their feet are not thick," said Thongpoon Aunjit, the village chief of Baan Sawai So in Buri Ram.

"In fact, the area was once their home."

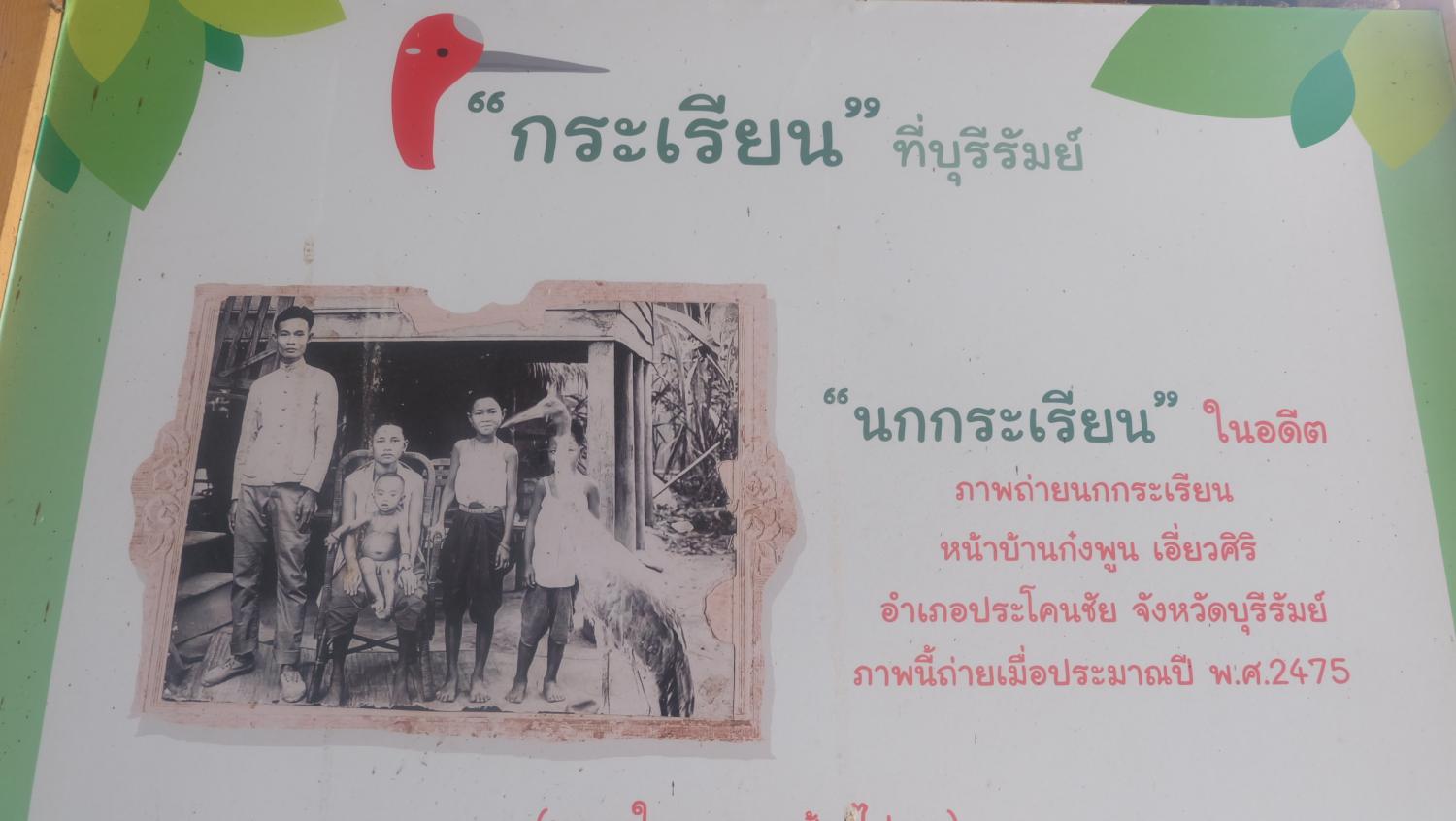

It is said that an old woman once saw a crane and stole its egg in childhood, but a picture is worth a thousand words. At the wetland and sarus crane learning centre there is an old photo of a family with the bird in 1932. It shows that the animal once existed here.

The Huai Chorakhe Mak reservoir and the Sanambin reservoir in Buri Ram were their natural habitats because they were surrounded by organic paddy fields. Thongpoon said when farmers refrain from using chemical fertilisers, they provide a friendly environment for water birds and earn income from conservation.

"It encourages farmers to grow organic rice and protect wild animals at the same time. The rice was titled sarus rice to reflect the connection between the water bird and the village," he said. "We also organise activities like bird watching and offer homestay accommodation to tourists."

Coexistence between humans and sarus cranes resonates in other cultures too. In Japan, the crane, or tsuru, is a legendary animal said to live for thousands of years, which makes it a perfect symbol of longevity. In China, people believe a photo or statue of a crane can make the elderly healthy and bring young people professional success.

"We believe that sarus cranes will bring good luck to paddy fields," said Pratana Aunjit, a community resident, who sees these tall water birds and hears their shrieks while flying over her house before dawn. Her words echoed a local version of harmony between farmers and wild animals, which had turned from foes to friends.

"We are proud they visit our land," she said.

Buy products to support conservation at facebook.com/sarusriceburiram and loveofcranes.com.