A dollar spent wisely on mitigation brings transformational economic benefits. So we can justify investing in both mitigation and adaptation, as China, India and many other countries are doing. Humanity can still, just, prevent catastrophic climate change if each country shoulders its share of climate responsibility.

Conservative columnist Matthew Hooton is using the latest line of climate deniers. ‘There’s nothing we can do to mitigate climate change; all we can do is get on with adaptation.’

New Zealand’s era of climate-change mitigation, which began with National signing the 1992 Rio Declaration and the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, is over. The physical and political effects of Cyclone Gabrielle mean the era of adaptation has begun.

But if we give up on mitigation, climate change becomes exponentially more damaging; thus adaptation gets exponentially harder to achieve and vastly more costly.

National had a brief window last week to leapfrog Labour and the Greens, to be first to rhetorically transition to adaptation and own the new politics of climate change. Finance Minister Grant Robertson quickly saw that risk and closed the window by raising the prospect of new taxes to pay for it.

Investing in mitigation reaps economic rewards, such as cleaner and more efficient technology, lower running costs plus the economic benefits of healthier ecosystems and greater biodiversity. That’s particularly true for our farmers. Switching to climate-compatible practices is the best business opportunity they will ever have, as I’ll explain below.

Thus, most money for climate mitigation comes from private sector investment in the new economy. To name just one example, the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change has 375 European members with more than Euro 51 trillion ($87 trillion) in assets.

Governments make some investment via taxes and borrowing for the likes of subsidies to help stimulate the transformation. But their mitigation finance is minor. However, governments end up paying most of the cost of adaptation, a huge bill which rises far faster if we ignore mitigation.

That's lost on Hooton, writing in the NZ Herald:

First, the definitions. Mitigation is trying to stop human-induced climate change by reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. It’s about not burning coal, transitioning to electric cars, planting trees and preventing cows from burping methane.

That simplistic definition assumes we largely keep doing what we’ve always done, minus the emissions. Mitigation, though, transforms economies. It makes them more productive while delivering substantial environmental, human and social benefits.

Here are just four examples of the myriad organisations helping to deliver those gains: Oxford Smith School of Enterprise and the Environment, Forum for the Future, Rocky Mountain Institute and the World Economic Forum.

Climate change adaptation is when you accept that climate change is going to happen anyway and get prepared for it. It’s about constructing more resilient infrastructure, building sea defences, updating zoning rules and farmers changing crops.

That equally simplistic definition assumes adaption is a fixed target – that we can work out how much we have to do then do it. But the scale and scope of adaptation is rising very rapidly, as the IPCC, the UN’s climate science body, reported last year in the impacts, adaptation and vulnerability phase of its 6th assessment report:

“The world faces unavoidable multiple climate hazards over the next two decades with global warming of 1.5°C. Even temporarily exceeding this warming level will result in additional severe impacts, some of which will be irreversible. Risks for society will increase, including to infrastructure and low-lying coastal settlements. Urgent action required to deal with increasing risks.

“Increased heatwaves, droughts and floods are already exceeding plants’ and animals’ tolerance thresholds, driving mass mortalities in species such as trees and corals. These weather extremes are occurring simultaneously, causing cascading impacts that are increasingly difficult to manage. They have exposed millions of people to acute food and water insecurity, especially in Africa, Asia, Central and South America, on Small Islands and in the Arctic.

“To avoid mounting loss of life, biodiversity and infrastructure, ambitious, accelerated action is required to adapt to climate change, at the same time as making rapid, deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions. So far, progress on adaptation is uneven and there are increasing gaps between action taken and what is needed to deal with the increasing risks, the new report finds. These gaps are largest among lower-income populations.”

Hooton says:

Very crudely, the political left has tended to concentrate on mitigation with the right more likely to emphasise adaptation. As a whole, New Zealand has focused mostly on mitigation to meet domestic emissions targets under the various UN declarations.

Extremely crude indeed. Mitigation and adaptation are inextricably linked. So far in New Zealand we’ve installed the key framework elements of our climate response – such as the Zero Carbon Act, the Climate Change Commission, national carbon budgets, a skeletal Emissions Reduction Plan and some high-level work on adaptation.

But we’ve worked so slowly and divisively in politics, business and society that so far we’ve achieved very little on mitigation, adaptation or transformation.

Just as roughly, the political tribes have divided on how fast New Zealand should move on mitigation. The left has tended to argue that we should lead the world to inspire action by the big five emitters, China, the US, India, the EU and Russia. The right has advocated being “fast followers”, moving in concert with our major trading partners.

Equally crude. Those advocating leadership focus on things which have long enhanced our international reputation, such as diplomacy. For example, under the Key government, Climate Change Minister Tim Groser was one of the leading early developers internationally of the principles that enabled the creation of the Paris Agreement in 2015.

‘Fast followers’ usually downplay what’s happening out there in the world, thus arguing we can take our time on climate action. They choose to ignore the likes of real clean tech progress such as the rapid ramping up of investment in renewable energy, China becoming the world’s largest maker of solar panels, wind turbines and electric cars, or the European Union’s Green Deal, the US’s Inflation Reduction Act, or Australia’s big shift to climate action following the election of its Labour-led government last year.

Both the Clark and Key-English governments also emphasised science. When ratifying the Kyoto Protocol in 2002, Helen Clark argued New Zealand should “catch the next wave in energy technology, rather than watch it pass by”.

Exactly. If we don’t mitigate, we’ll miss the economic and tech transformations underway. We will remain stuck in our late 20th century economic model of being hard-working, poorly paid and unsustainable producers of low value products.

Worse, we will fail to learn how to bring people together in politics, society and the economy to learn new ways of collaborating to solve the incredibly complex issues of climate mitigation, adaptation and transformation. That would put us even further behind the pack internationally.

At the failed Copenhagen climate conference in 2009, where the presidents of China and the US arrived only to discover there was no real negotiating text, the most meaningful outcome was the launch of Tim Groser’s Global Research Alliance on agricultural greenhouse gases. It now involves scientists from over 60 countries working to reduce emissions from food production, including through biotechnology.

Agricultural emissions represent over 10 percent of greenhouse gas emissions globally. The idea is that if New Zealand scientists could find ways to halve that, global emissions would fall by over 5 percent — doing 30 times as much good as New Zealand reaching net zero domestically.

Yes, the Alliance was exactly the sort of leadership we should be offering the world, given our agricultural strengths. The Alliance is making good progress, and NZ is still involved.

However, we have failed abysmally so far to speed up our reduction in ag emissions from their very slow historic rate of improvement. That’s mainly because the dominant mindset in farming is utterly defensive. It refuses to acknowledge the rapid shifts to more climate compatible farming underway in some other countries. Quite simply, we’re falling behind some of our competitors, as this annual OECD report on agriculture showed last August.

Thankfully, though, a few of our major farming businesses are deeply engaged in transforming their practices, such as Synlait Milk, Silver Fern Farms and Pāmu.

Meanwhile, Fonterra and its farmers, our largest single source of greenhouse gas emissions, accounting for 21 percent of NZ’s total emissions, has yet to set a target for reducing methane, their overwhelming type of emissions. It’s seriously out of step with its largest customer, Nestlé, and its competitors such as FrieslandCampina and Arla which have ambitious climate targets.

With that exception, New Zealand’s 30-year climate-change mitigation strategy has completely failed.

No. Farming is not currently a beacon of hope. Instead, the sector’s refusal to understand the rewards it would gain from mitigation and adaptation (such as reduced input costs, higher product premiums and in due course new sources of income such as biodiversity credits) is one of the main reasons why our efforts to progress on mitigation and adaptation are proving so tortuous and ineffective.

Delusions that China or India would be inspired by our climate-change policies have, as predicted, proven fanciful. From the 1992 Rio Declaration through to just before Covid, world GHG emissions increased by 57 per cent. Of our three main trading partners, China’s emissions were up 261 per cent, Australia’s by 20 per cent and the US’ by 2 per cent.

Indeed, world emissions have risen by half in the past 30 years. But that’s mainly driven by growing populations and economic progress in developing countries. So, of course China’s emissions have nearly trebled, while India, Indonesia and Brazil have shown strong growth too.

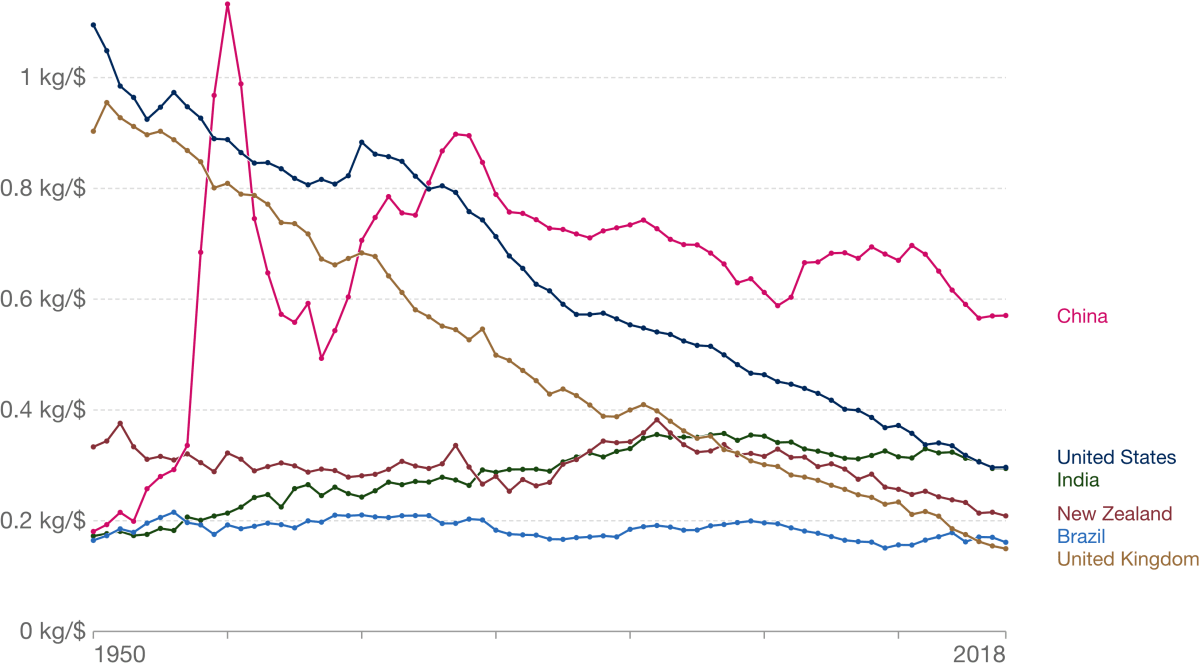

It’s only fair they should be allowed to develop. Thus, the true way to compare them to developed countries like ours is on emissions per unit of GDP (that is, emissions intensity). This chart shows how those have tracked since 1950 compared with the likes of us, the US and UK.

Carbon emission intensity of economies

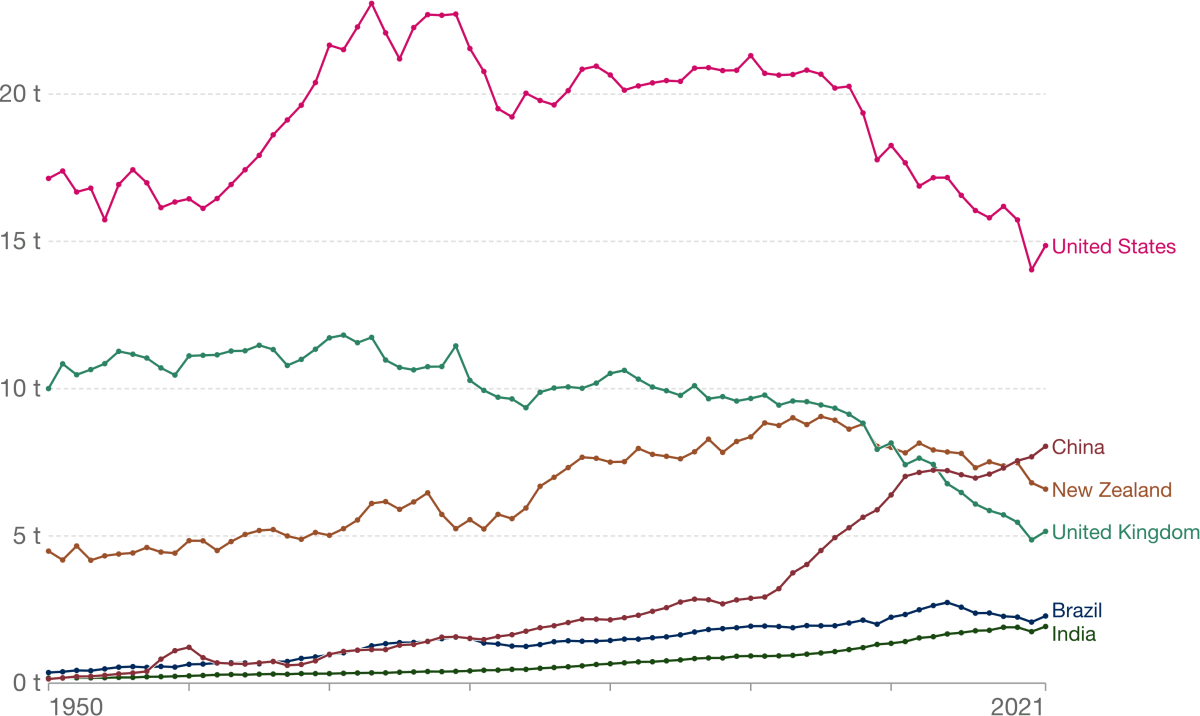

Another fair measure is emissions per capita, which shows India and Brazil are still a long way behind us, while China now exceeds us.

But developed countries like us and the UK are also manufacturing less than we did and are importing from China instead. So we should ‘own’ some of those Chinese emissions.

Per capita CO2 emissions

Ensuring developing countries can progress in climate compatible ways is another very strong reason for all countries to push hard on mitigation, including us. Cutting emissions through the likes of circle economy principles also delivers benefits such as far more sustainable use of natural and human-made resources, while increasing the health, resilience and productivity of our ecosystems.

Greta Thunberg quickly worked out that promises at the annual United Nations jamborees, which tens of thousands of bureaucrats and hangers-on cynically attend each year, were worthless.

That’s plain wrong. Over the past nearly 30 years, the United Nations' COPs (Conference of the Parties to its climate convention) have achieved the very hard goal of getting all the countries of the world bar a few) to agree to the likes of the Paris Agreement and a raft of supporting agreements. Last year’s COP in Egypt was a good example of that continuing progress, as I reported in this column.

Yet, New Zealand is still on climate glide time, as I also noted in that column. We can’t bring ourselves to engage deeply and purposefully on mitigation, adaptation and transformation.

In any case, New Zealand’s mitigation record provides no soapbox to lecture others, with our emissions having risen 15 per cent since 1992. Under each of the Bolger-Shipley and Clark governments, they rose around 7.5 per cent, before falling nearly 1 per cent under John Key and then rising 1 per cent in the first two years of Jacinda Ardern.

Sadly, having plunged dramatically over the previous decade, imports of coal quadrupled while Ardern was Prime Minister and the amount burned to produce electricity increased five-fold. If electric cars use coal-produced electricity, they are no better for the environment than petrol ones.

That extrapolation is nonsense. Coal still only generates a tiny proportion of our electricity. An EV that draws only 5 percent of its electricity from a coal-fired plant is still far cleaner than a petrol or diesel car. And that proportion is unlikely to rise much given our growth in generation by renewables aided, for example, by better access to the national grid.

Another very coarse generalisation — with an even greater number of obvious exceptions — is that the political right preferred mitigating climate change with market mechanisms like the emissions trading scheme (ETS), while the left preferred direct interventions.

Allowed to work properly, an ETS can’t help but deliver zero net emissions by the due date. But no government could allow an ETS to work as intended if it meant true market prices for agricultural emissions, destroying rural communities as pastoral farming is converted to forestry, and raising global emissions as our agricultural production moves to countries with inferior environmental records.

If the worst fears of He Waka Eke Noa were realised in terms of a 1.4 percent reduction in dairy production in New Zealand, it would take the global dairy industry only three hours per year to make up the difference. Thus, the real opportunity to our farmers is to help show how dairy and meat farming can over time become climate compatible.

Moreover, Hooton’s assertion that all we need is an excellent ETS is classic ACT. ‘If only we had a pure ETS, the high price of carbon would be the only tool we’d need to achieve our climate goals.’

That’s just another denialist line to try to head off the vast array of targets, policies, programmes, regulations, funding, investments and other mechanisms we need to achieve the incredibly complicated tasks of climate mitigation, adaptation and transformation.

Direct interventions, like Groser’s successful Global Research Alliance, Shane Jones’ failed billion-tree project and Ardern’s counterproductive ban on oil and gas exploration, were necessary.

Exactly. So, we need more. And the more we do, the better we’ll do them.

The cyclone has changed everything. It is evidence that the left tended to be right about the science, but underlines that the right tended to be right about the international politics. New Zealand is not at greater risk of extreme weather events because of anything we have done, but because China, India, Indonesia and Brazil have so massively increased their emissions.

From the start, it was obvious they would never change path.

But the right was wrong about the science. It turned out we didn’t have time to deny and delay. And the right is also wrong about the international politics. You can’t just pick on large emitters (developed and developing) and say they have to tackle the climate crisis. Every country, however small, is responsible for its emissions and for helping to develop solutions.

No small country can produce blockbuster climate solutions. But we can produce a wealth of innovation and best practice across mitigation, adaption and transformation that will contribute to global efforts. The vast challenges require an all-of-humanity response.

And contrary to Hooton’s cynicism about the likes of China and India, they are making massive positive responses to climate, as Brazil is, now it is no longer ruled by a far-right autocrat. But they, like every other country, are still finding it far too hard to change some things.

Some mitigation strategies will continue. The GRA is still New Zealand’s biggest single potential contribution, with everything else globally irrelevant.

Wrong, the Global Research Alliance has yet to make any significant reduction in our agricultural emissions, as I noted above. It could, though, if our farmers finally got serious about climate mitigation and adaptation.

That doesn’t mean our emissions won’t fall, as car manufacturers stop making petrol and diesel vehicles and electric cars become the only option — hopefully powered by hydroelectric, solar or nuclear power rather than coal.

Coal is irrelevant to us, as is nuclear, given our abundant source of clean, renewable energy and fast improving technologies for electricity storage.

That date will probably arrive sooner than expected, requiring charging stations throughout New Zealand if we are to keep using our roads.

Perfectly doable, if we put our minds to it.

Similarly, those road and rail networks need radical upgrades, as do some stormwater systems. A combination of sea defences and zoning changes is needed, especially on the coast. As always, farmers will need to produce the stock and crops that make sense for the new conditions. Massive new investments are needed in the military, to provide more capability to respond to weather events and because climate change is expected to create global instability.

Without mitigation, we’ll have runaway climate change which makes it impossible to plan and invest in adequate adaptation. Instead, the task for all of us is to make sure everything we do helps reduce the drivers of climate change and helps make nature more resilient to the climate change we have. Farmers’ potential for action, for example, is so great they would become climate heroes.

Those who have demanded greater investment in mitigation for 30 years are right that this will all cost more than had the world prevented climate change. But they are wrong if they think New Zealand’s mitigation efforts would have made any difference. Every dollar we now spend on domestic mitigation that is not matched by a thousand dollars spent by China and India is a dollar we cannot invest in adaptation.

A dollar spent wisely on mitigation brings transformational economic benefits. So we can justify investing in mitigation and adaptation, as China, India and many other countries are doing. Humanity can still, just, prevent catastrophic climate change if each country shoulders its share of climate responsibility.

National could have made these points, positioning itself as forward-looking on climate change while Labour and the Greens remain in denial. Alas for the right, Robertson got in first, and the debate is now about how to pay for it. Robertson is signalling that he favours tax. National indicates that it prefers borrowing.

That would be a rational climate-change debate to have in election year.

Hooton believes adaptation is the only option left to us, and how we pay for it is the only question still to answer. If National and ACT took his advice, voters would have every reason to despair.