The lives of galaxies can be extended if their supermassive black holes that provide them with "hearts and lungs" to support their "breathing" and prevent them from growing too large.

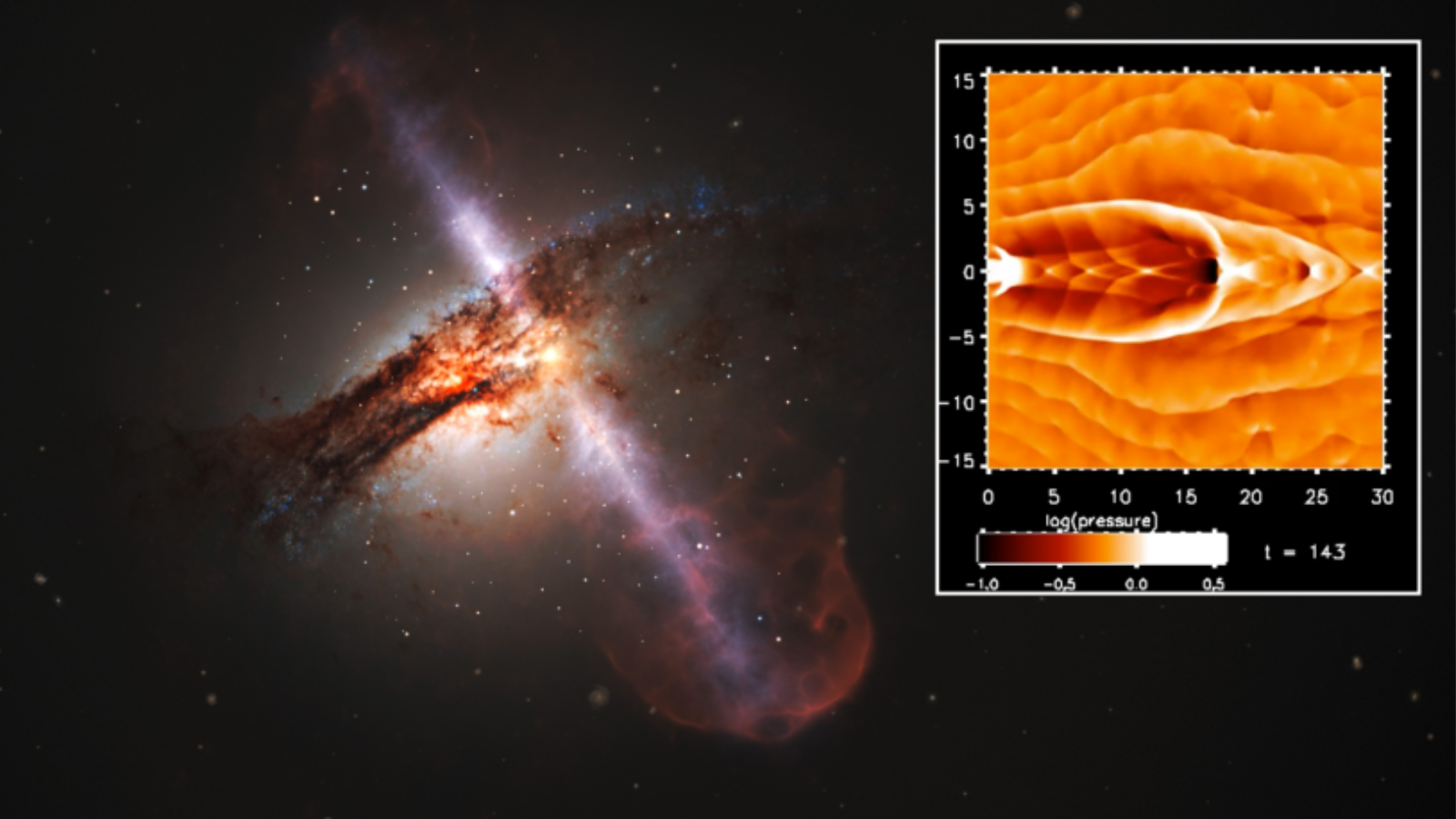

That is the suggestion of new research indicating the universe would have aged much faster and would today be filled with "zombie" galaxies containing dead or dying stars were it not for the supermassive black holes thought to sit at the hearts of all large galaxies. The astrophysicists behind the findings compare jets of gas and radiation that supermassive black holes blow from their poles to the airways that feed our lungs.

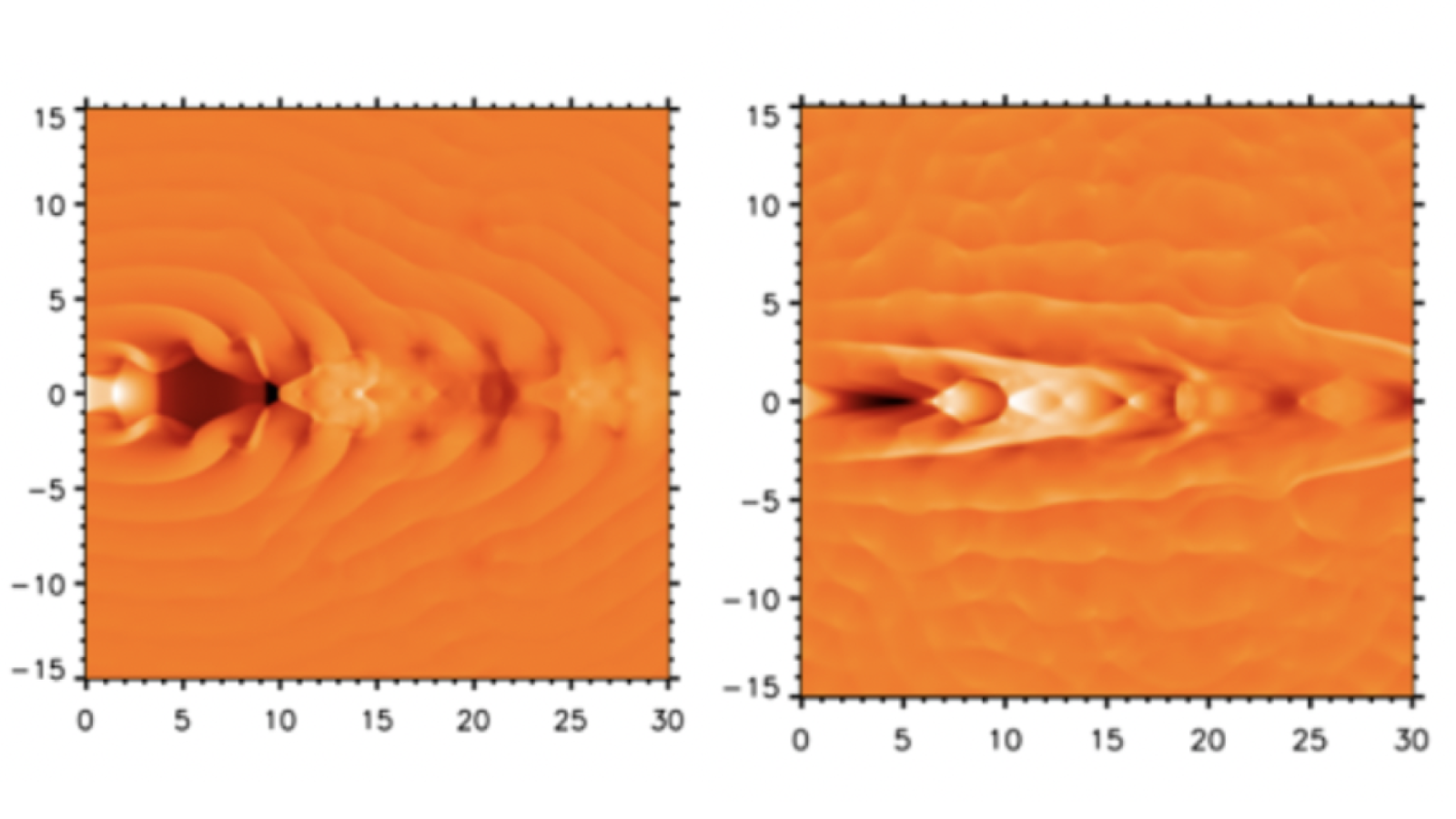

The University of Kent crew thinks pulses from each black hole "heart" cause shock fronts that oscillate back and forth across both jets. This is similar to how a part of our body called the thoracic diaphragm moves up and down inside our chest cavities to inflate and deflate our lungs.

In galaxies, this respiratory-like action transmits the energy of the supermassive black hole-blown jets to the surrounding medium, like how on a cold winter morning you can breath out warm air into the colder air. Stars form when interstellar gas clouds cool and are allowed to condense. That means this "breathing out" can slow star formation, curtailing galaxies' growth.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope sees an ancient black hole dance with colliding galaxies

The team arrived at this conclusion after analyzing simulations designed to replicate the impact supersonic supermassive black hole-blown jets might play in inhibiting galaxy growth. The simulations showed that the supermassive black hole heart can pulse, creating high pressure in the jets — almost like a human suffering from high blood pressure, or "hypertension."

When this occurred, the team saw the jets beginning to act like bellows, launching soundwaves that rippled through surrounding material of galactic gas and dust.

"We realized that there would have to be some means for the jets to support the body — the galaxy's surrounding ambient gas — and that is what we discovered in our computer simulations," team member Carl Richards, a Ph.D. student at the University of Kent, said in a statement. "The unexpected behavior was revealed when we analyzed the computer simulations of high pressure and allowed the heart to pulse."

This sent a stream of pulses into the high-pressure jets, causing them to change shape as a result of the bellows-like action of the oscillating jet shock fronts. The researcher added that these jets expanded "like air-filled lungs." In doing so, they sent ripples of pressure into the galactic material around them, with this stopping the growth of galaxies in the simulations.

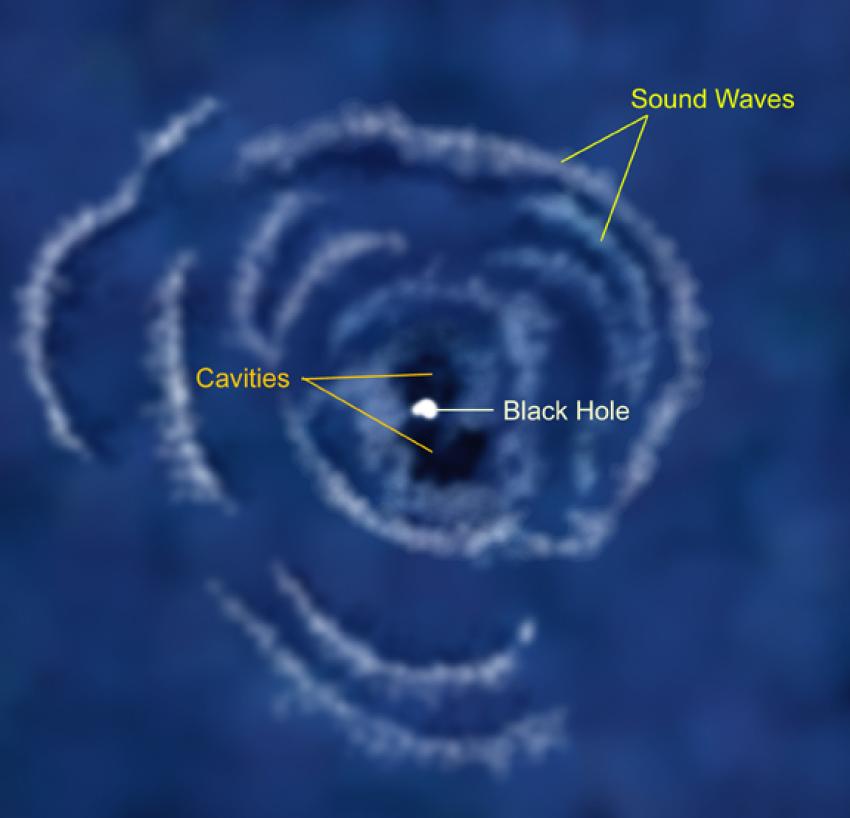

Away from the team's simulations, there is some other evidence of this phenomenon in real galaxies. For instance, around 240 million light-years from Earth in the Perseus galaxy cluster, astronomers have seen evidence of large gas bubbles in this collection of thousands of galaxies immersed in a vast cloud of multimillion-degree gas. These are believed to be the result of soundwaves rippling through the galactic medium in this cluster.

The equilibrium between black hole activity and the flow of gas into galaxies is extremely difficult to achieve — however, as supermassive black holes require a steady supply of gas and dust to create jets.

"Breathing too fast or too slow will not provide the life-giving tremors needed to maintain the galaxy medium and, at the same time, keep the heart supplied with fuel," team member and University of Kent researcher Michael Smith said in the statement. "To do this is not easy, however, and we have constraints on the type of pulsation, the size of the black hole, and the quality of the lungs."

The team concluded that a galaxy's lifespan can be extended with the help of its supermassive black hole "heart" and that black hole's jet "lungs" blowing from its core as they inhibit growth by limiting the amount of gas collapsing into stars from an early stage.

Without this mechanism, many galaxies would have exhausted their fuel supplies needed for star formation by now in our 13.8-billion-year-old universe. As a result, they would have "fizzled out," with most galaxies resembling so-called "red and dead" zombie galaxies at this point, filled with ancient burned-out stars.

The team's research is published on July 12 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.