Keep up to date with the latest northern lights news with our aurora forecast live blog.

The sun appears to have woken from its slumber with an impulsive X-class solar flare, the most powerful class of solar flare.

The dramatic eruption originated from sunspot region 3912, reaching its peak at 4:06 a.m. EST (0906 GMT) on Dec. 8, and was accompanied by a coronal mass ejection (CME) — a large plume of magnetic field and plasma from the sun. When CMEs (also known as solar storms) hit Earth's magnetosphere they can trigger active geomagnetic storm conditions resulting in impressive auroras. Earth may receive a glancing blow from the CME released yesterday (Dec. 8) but only mild impacts are predicted, according to Space Weather Physicist Tamitha Skov.

"The #solarstorm launched will graze Earth to the west. Sadly, the coming fast solar wind streams might deflect the structure even further to the west. Expect only mild impacts by midday December 11," Space Weather Physicist Tamitha Skov wrote in a post on X.

What are solar flares?

Solar flares are powerful bursts of energy originating from the sun's surface that release strong bursts of electromagnetic radiation.

Solar flares are categorized into five classes: A, B, C, M, and X. Each step up represents a tenfold increase in strength. A-class flares are the weakest and generally go unnoticed on Earth, while X-class flares are the most intense and can have significant impacts, such as disrupting satellites and causing radio blackouts. Within each class, a numerical scale (e.g., X1, X2, X10, etc.) provides more detail about the flare's energy level.

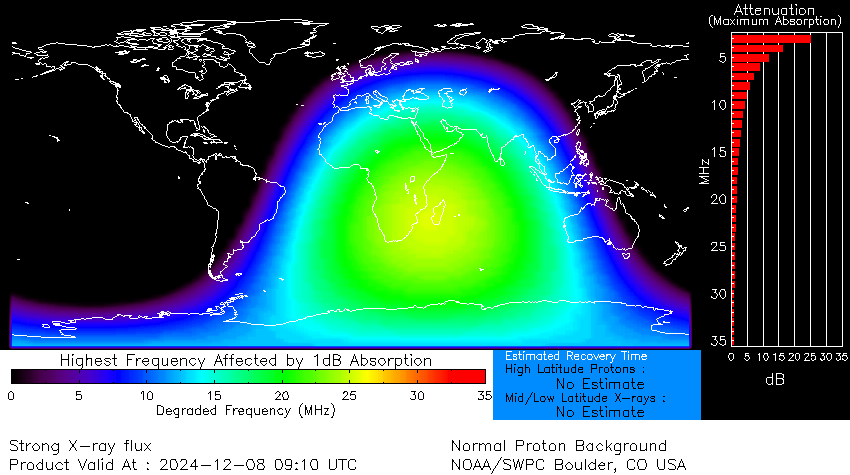

Radio blackouts

Following the eruption of an X-class solar flare, shortwave radio blackouts were observed over southern Africa, the area illuminated by the sun at the time of the outburst. These radio disruptions, which are typical during powerful solar events, are caused by the intense release of X-rays and extreme ultraviolet radiation accompanying the flare.

Radiation from solar flares travels to Earth at the speed of light, ionizing the upper atmosphere when it arrives. This ionization increases the density of the atmosphere, affecting high-frequency shortwave radio signals used for long-distance communication. As these radio waves pass through the electrically charged, ionized layers, they experience energy loss due to more frequent collisions with electrons, which can weaken or even fully absorb the radio signals.