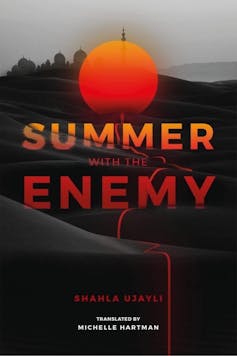

Wherever you spend your summer, allow yourself to be transported to Syria and immerse yourself in the world of Shahla Ujayli’s sweeping historical novel Summer with the Enemy.

The ongoing devastation of the war that began in 2011 has brought Syria to the world’s attention. Reading a Syrian novel is a way to experience its deep and rich culture, history and literature beyond the headlines.

Summer with the Enemy was a finalist for the prestigious the International Prize for Arab Fiction, sometimes known as the “Arab Booker Prize.” It was written in Arabic by Ujayli, one of the country’s most prominent women writers; I translated it into English one year later.

City of Raqqa

Ujayli’s evocative storytelling conjures up the city of Raqqa, from its past as a dusty provincial town beginning in the 1920s, through the 20th century, and its subsequent occupation and 2017 siege by Islamic State militants (ISIS). In Summer with the Enemy, the main characters eventually must leave Raqqa behind for a new life in Germany.

A detailed and intricate portrait of three generations of one family in this northern Syrian town, Summer with the Enemy combines historical fiction with a romance and a coming-of-age story complete with an tale of first love. The characters challenge western stereotypes about Arab Muslim women — that they need to be “saved” from oppressive realities — through depictions of their active, diverse and complex lives.

The town of Raqqa is so important to the story that one critic claims it is actually a character in the novel.

Family drama, first love

It’s hard not to feel compelled by the Raqqa of the past, with its tightly knit, multi-ethnic community, full of local conflicts and family drama.

Each story the grandmother tells has the younger generations on the edge of their seats, waiting to hear about a scandal, an illicit affair, a failed love match or an exotic trip abroad. She always leaves her audience wanting more when she rises mid-sentence to stir the coffee on the stove, tension building.

During the summer of the title, some time in the ‘80s, the protagonist, Lamees, rides horses along the Euphrates, an expansive desert surrounding her, and dreams of an equestrian future.

Horses means she can avoid her mother. Their relationship had become tense, after Lamees’s father left Syria, never to return. Lamees resents her mother’s incipient love affair with a visiting German professor, Nicolas, the enemy of the book’s title. The daughter acts as a local guide to Nicolas, who leaves when his research is done. The women call upon Nicolas later to find passage to Germany after the fall of their beloved city.

Revisiting memories of Raqqa

About 10 years after the fictional Lamees was living in Raqqa, experiencing the Assad government’s belt-tightening policies, I embarked upon the long trip there from Damascus with a university friend. In summer 1995, my visit revealed a Raqqa much like the one Lamees showed to her German enemy.

But when I was in Raqqa in the '90s, I had no idea that more than 20 years later I would be video-chatting with a famous Syrian author from the town. Ujayli was giving me a sort of interview before I translated her novel. Among other questions, she asked me: “Have you ever been to Raqqa?”

I was pleased to be able to answer yes — I had visited long before most people outside of Syria had ever heard of Raqqa. I prepared to translate this novel by revisiting that journey through talking to Ujayli and by looking back over old photographs, revisiting memories of the place.

Translating Arabic into English

In an interview about my translation process, an interviewer asked me the same question.

Translating Arab women writers from Arabic into English has a difficult history: Many translations have been so changed as to be unrecognizable.

As scholars have shown, the entire thrust of a book can change with translations creating new titles, sections edited and censored, narrative voices voices altered and entire characterizations changed.

I worked with Ujayli to convey the details of the text accurately, while also finding words to give the new English text as much life as the Arabic original.

In the summer of 2019, I translated the novel in a Lebanese mountain village. Just across the border, Syria was visible on a clear day. That summer we could hear the echoes of bombs being dropped across the valley.

Focused on conveying the details and complexities of of the book, I felt the tension between the book’s beautiful depiction of the past and Ujayli’s searing depiction of life under ISIS occupation, fierce battles in Raqqa and Lamees’s subsequent escape to Germany.

Lessons in empathy

The utter destruction of Raqqa between 2013 and 2017 and any semblance of the previous lives lived there felt so real.

Lebanon is a country still bearing the scars of its own long civil war (1975-90). The reverberations of the bombs we heard that summer in Lebanon had an unmistakable impact on the translation. The words a translator chooses to translate are always impacted by their surroundings.

Ujayli’s novels offer “lessons in empathy,” as noted by Marcia Lynx Qualey, founding editor of the website ArabLit.

Packed with humour, drama, romance and 100 years of history, Summer with the Enemy puts women centre stage, will take readers to the heart of one woman’s coming of age in Syria — and offer insights into its past and present.

Michelle Hartman does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.