Margaret Sullivan cringed one day when a former colleague at The Washington Post, critic Carlos Lozada, tweeted with exasperation about books pitched to him as combinations of memoir and manifesto.

That's exactly what she was writing.

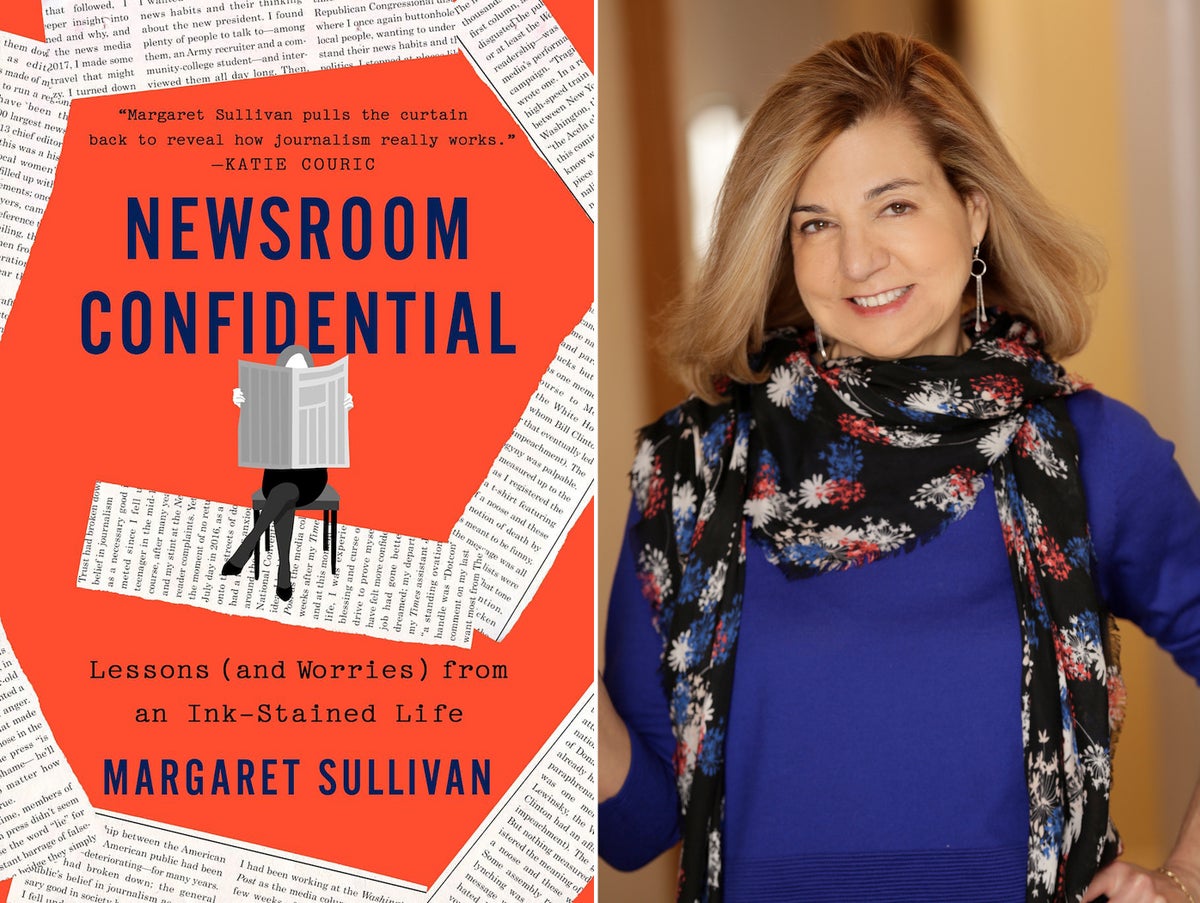

Sullivan's “Newsroom Confidential” traces her career from The Buffalo News to The New York Times and The Washington Post, but its meat lies in the challenge she puts to fellow journalists in the Trump era: Too many times she saw journalists slow to recognize threats posed to democracy during his presidency and now, with Donald Trump poised for a potential comeback and followers his taking cues, Sullivan said she worries that reporters are unprepared.

“There still seems to be a tendency to not want to offend,” she said, “to not want to offend the Republican establishment, to not offend the Trump Republicans, but rather to normalize them with democracy on the brink. I don't think that's the right approach.”

Several news organizations now have special beats to cover threats to the electoral process. Sullivan acknowledges that work, and praises Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, radio station WITF, which reminds listeners on a regular basis about local legislators who rejected the results of the 2020 election.

Moving forward, journalists need to stand for truth and not amplify the words of politicians who refuse to acknowledge it, she said.

The issue hasn't gone away, as illustrated this past weekend when CNN's Dana Bash sparred with Kari Lake, Arizona's Republican candidate for governor. Bash repeatedly asked about false fraud reports and pressed Lake about whether she would accept her own election results. Lake complained Bash was concentrating on old news.

“I don't think it's about being aggressive,” Sullivan said. “I think it's about framing things differently so we don't see these very high stakes politics as a game, we don't see it as horserace, we don't see it as entertaining. We see it as extremely consequential and happening before our eyes.”

Press criticism is not new; for instance, the media's performance before the Iraq War was widely condemned, said Will Bunch, columnist for the Philadelphia Inquirer. But not many who raise concerns have Sullivan's stature, he said.

“This criticism isn't coming from the outside,” Bunch said. “It's coming from someone who is in many ways the ultimate insider. People at the highest levels are going to have to engage with someone like Margaret.”

But, Bunch conceded, “listening to her and doing something in response are two different things.”

The concern is whether hostility toward the press has reached a point of no return. Too many Americans are tuned out or more interested in their own beliefs than truth, Sullivan said.

“Both of those things are very, very troubling,” she said. “Do I think we're too far gone? I don't want to think that.”

Born and raised in nearby Lackawanna, New York, Sullivan was a summer intern in 1980 at what was then called the Buffalo Evening News. She rose through the newsroom to become its top editor in 1999. She describes sexism she encountered along the way, like when an older male editor took credit for her idea.

They were good years, grounding years, for newspaper work.

“Journalism offered a viable career path,” she wrote. “Not a great way to get rich, perhaps, but certainly a way to earn a living wage. As a bonus, it struck me as exceedingly cool.”

She wasn't intimidated when she spotted an opening for The New York Times' public editor job in 2012, pursuing it hard. Local newspapers were contracting, and she didn't have the stomach for steering The Buffalo News in a diminished state.

The public editor is a thankless job. You're situated in a newsroom, charged with publicly evaluating the work of those around you. Nobody likes to be criticized, whether it's someone at the highest levels of journalism or the person serving you coffee.

Sullivan became known for her blunt writing about the Times during her years there, tackling such issues as the overuse of confidential sources, its coverage of Hillary Clinton's emails and national security issues, even poking fun at so-called fashion trends touted by the Styles section.

In four years, she never had a completely comfortable day, she wrote.

“I liked being an outsider,” she said in an interview. “It's important to me. I was an outsider at the Times and when I felt like I was losing that a little bit — I was asked to stay longer — I left of my own volition because I thought these people were starting to feel like my friends and I didn't think that was healthy.”

The Times had one more public editor after her and has since eliminated the public editor's position, a decision she disagrees with but doesn't expect will be reversed.

She moved to the Post as a media columnist, never realizing how so much of her time would be spent writing about Trump and his norm-busting presidency.

Five years later, feeling burnt out from column writing, she sensed it was time to move on again. She had written a book on the decline of local news and found she liked the form. She quit the Post and wrote “Newsroom Confidential,” and her next step is teaching at Duke University.

What Sullivan has left behind is the bluntest of warnings. American journalists, she wrote, “should be putting the country on high alert, with sirens blaring and red lights flashing.”