After decades covering federal politics in Canberra, my embarrassment at not knowing Warren Denning’s Caucus Crisis: The Rise and Fall of the Scullin Government (1937) was partly assuaged when an older colleague revealed the same.

Written by a lion of early political reporting in Canberra, it was the first of what would become a line of political books to emerge from the federal parliamentary press gallery.

Review: Political Lives: Australian Prime Ministers and Their Biographers – Chris Wallace (UNSW Press).

Denning’s book was also the first quasi-contemporary exposition of a dramatic political upheaval – in this case, how the Great Depression rocked politics and overwhelmed the new Scullin Labor government. That government’s defenestration in January 1932 earned it an enduring place in our electoral records. It is (still) the only single-term federal government since the two-party system settled into its current pattern.

“Before Denning, no Australian journalist had let readers in to the private interactions between them and the politicians they reported on in this way,” writes historian and biographer Chris Wallace in her engrossing book Political Lives: Australian Prime Ministers and Their Biographers. Caucus Crisis, she argues optimistically,

was something of a “wholesale” classic, notable in the political confines of Canberra because of its continuing reputation and availability to politicians and journalists through the Parliamentary Library, but not widely known to the public.

While acknowledging that Denning’s account was “contemporary history rather than contemporary biography”, Wallace, a professor at the University of Canberra, justifies its inclusion in her book by noting that it

relies heavily […] on brief evocative portraits of key political players including Jack Lang, E.G. “Red Ted” Theodore, “Stabber Jack” Beasley, and Scullin himself.

In this sense, Caucus Crisis was a vanguard of journalism. It set out to humanise both political events and their reportage, while conforming to the standard devices used to temper excessive subjectivity.

Practical fiction

The admixture is familiar to Wallace as an academic historian and erstwhile parliamentary journalist, and it gives Political Lives its narrative momentum and scholarly heft. Her admiration for Denning’s boldness in both of these spheres shines through in simple passages like this:

Denning’s account is innovative in several ways, not least making the presence, role and anxieties of Depression-era political journalists explicit. Denning lets readers in too, on the behind the scenes interactions between journalists and politicians.

For so long, the practice of “serious” political journalism has evinced a haughty conundrum – that of the scribe being simultaneously “in the room”, having selflessly pursued access for the reader, and yet also being invisible in that room, devoid of material form, like a camera in a movie. The diligent reporter exclusively reports, does not seek to shape things, and never, ever, uses the perpendicular pronoun “I”.

This state of feigned non-existence and perfect neutrality has always been a practical fiction. Journalists know their presence among political practitioners alters things. Politicians know it too. Paul Keating famously opposed televising parliament precisely because it would change behaviour during parliamentary combat.

Only recently have journalists begun to cast aside this theatrical conceit. Leading practitioners, such as the Guardian’s Political Editor Katharine Murphy, openly eschew what she has called “the absurd voice of God” narrator. For Murphy, the contextual dynamics of the relationship are integral to the story, inseparable and germane.

Reporting on a hard-won 2020 interview for Quarterly Essay with then prime minister Scott Morrison, Murphy began her account:

He’ll tolerate this conversation, he might even enjoy bits of it if we both choose to be present and avoid lapsing into passive aggression. […]

His opening gambit as we take our seats is “I haven’t done a lot of this”. He means sit-down conversations during the pandemic, or indeed at all, during his prime ministership […] he’s not certain this interview should be happening. I’m not a media intimate of the prime minister, I don’t know the secret handshake of the “yes, mate” club […] periodically I irritate him, and we both know I’m not much use to him.

There’s a kind of revelatory completeness here. The reluctant granting of the interview is as much a news element as the content arising from it. The author is admitting to personal history, conveying the political friction, so as to be judged against it. Or not. And there is the unmissable implication that, as with an authorised biography, the politician has motives and plenty of skin in the game.

Professional candour

One suspects this is a professional candour Wallace would applaud and would say amounts to deception if omitted. Political Lives begins with an extraordinary explanatory note in this vein, in which Wallace gives her reasons for withholding a biography of Julia Gillard she had already researched and written, lest it be immediately weaponised:

Both Rudd and Abbott were coming for her. Gillard’s life story contained its share of lesser elements. Enemies in opposition, the government, and the media, were poised to cherry-pick my biography for exploitable stories.

In the febrile atmosphere building around the nation’s first female prime minister, Wallace wondered whether aiding and abetting this misogynist frenzy was right:

Whatever one’s view of Gillard, her prime ministerial performance and her government, was this fair, was this what a biography should do? I flew home to Canberra and wrote to my publisher to say I had decided to put the biography aside and return my advance.

The story lays bare Wallace’s inspiration for Political Lives and a provides a useful context for the book’s dissection of power, public curiosity, and the particular reasons biographies get written about serving or aspiring prime ministers in the first place.

The ethos of Political Lives is the crucial relationship (where it lasts) between biographer and subject – “crucial” but generally unexplored, as mere scaffolding behind a stage set. Restricting her field to the 20th century, Wallace is particularly interested in the utility of the biography. This invariably means the intent of its subject politician. How did the proposal come about? Whose interests did it ultimately serve?

In this regard, the contemporaneous biography is of particular salience, because it alters public perceptions of a political figure in real-time.

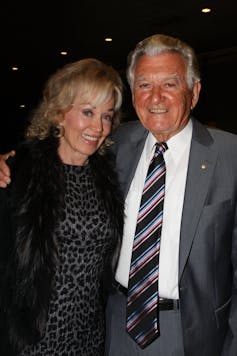

The most celebrated modern case is Blanche d’Alpuget’s Robert J. Hawke: A Biography (1982). So many of the questions pertinent to contemporary biographies coalesce in this one case. D’Alpuget’s closeness to her subject is only the most obvious, given she subsequently married Hawke. Yet Wallace’s admiration for the rigour of d’Alpuget’s work is clear.

The charismatic Hawke was in his first term in federal parliament in 1980, but by 1982 he was pushing hard for the Labor leadership. His backers were convinced his relatable larrikin popularity and rapier wit could sweep the dour Malcolm Fraser from the Lodge in 1983.

That larrikin past came with skeletons: affairs, drunken excesses, family grievances, friendships bulldozed, tempers lost. In short, a rich seam of stories for journalists to mine, guaranteeing a drip-feed of difficult revelations.

But what if Hawke got there first via a warts and all confession? The politician stripped bare, then born afresh. Not for the first time, the biography became an instrument of strategy – a chrysalis leading to the final form.

Biograpy as intervention

Wallace’s final chapter, titled “The political biography as political intervention”, ties it all together.

We read that there have been seventeen such biographies overall, including some which, like Hawke’s, were penned prior to their subjects ascending to the highest office. We also learn that World War I prime minister Billy “The Rat” Hughes was the subject of two of three contemporaneous biographies written about Australian wartime prime ministers. (The third concerned John Curtin in 1943.)

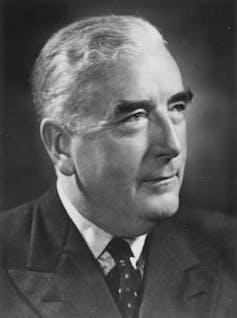

Fascinatingly, Robert Menzies, Australia’s longest-serving prime minister, eschewed the political biography as a serious form. In the foreword of a 1948 treatment of Edmund Barton – Australia’s first prime minister – Menzies decried such works as

usually extravagant and largely worthless. They are written, as a rule, by ardent admirers, and rarely possess any critical quality. They are, in short, propaganda documents to be discounted by the objective student.

Menzies preferred the “detached historian”, who could study a “statesman” after the fact, although even in the 1940s he was lamenting that sources were unreliable: ministers speeches were often not their own words; the practice of social letter writing had become utilitarian and “commercial”, thus ceasing to yield real insights into underlying views and character traits. What would he make of emails and selfies?

As for journalists, “heaven forbid” they should write such works. Menzies complained of “partisan writers” aiming to create a popular picture with legends that were “basically false”.

Menzies’s perspicacity about contemporary biographies and journalistic frailties is to be admired, bearing in mind that his previous stint as prime minister had ended in humiliating failure. His public standing as arrogant and elitist might well have benefited from the re-packaging a contemporaneous biography, as “intervention”, could have delivered.

As prime minister, Menzies did subsequently cooperate with a contemporary biographer, though the book never saw the light of day. Wallace takes the reader into that “contested” mystery too:

The case of the “Menzies Biography Mystery”, as the press tagged Allan Dawes’ abortive book, points to the likely role of shifting political fortunes in decisions about them: the atmospheric may change considerably as the project proceeds.

Here, as in so many places throughout her work, Wallace’s analysis benefits from its foundations in both academic and journalistic terrain. No mere anthology, Political Lives is a book about the politics of political books. It invites the prospect of a new field of historiography and political evaluation, with fresh metrics for understanding politics through its mediation, and through one of its most prevalent but opaque drivers: personal ambition.

On his program The Weekly, the political satirist Charlie Pickering proclaims “we’ve watched all the news, so you don’t have to”. Wallace has read all the biographies so you don’t have to. Yet somehow she makes you want to read them as well. One suspects the creative impetus of this book could only germinate in the mind of that rare category of person, the formally trained journalist-historian-biographer. From its first page, Political Lives entertains, but then it does something far more valuable, something only the best historical writing does: it lights up the present by illuminating the past. Who could want more?

Mark Kenny does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.