The group behind songs like “End of the Road,” “It’s So Hard To Say Goodbye To Yesterday,” and “I’ll Make Love To You” is one of the most successful R&B acts of all time. But a recent tweet from BET’s account gave them a different title: “the blueprint to boy bands.”

The tweet praised the legacy of Boyz II Men, hailing Boyz II Men as the boy band that birthed a legion of chart-toppers a decade later. It’s undeniable that the group was a major influence on a wave of white pop artists who took the airwaves by storm in the early 2000s. I also happened to find a list of the Top Ten Boy Bands Ever from BET that included Boyz II Men amongst its entries. And on December 6, Boyz II Men will be featured in ABC’s seasonal special “A Very Boy Band Holiday.” But is Boyz II Men a “boy band”?

The term “boy band” became popular in the late 1990s/early 2000s, as a wave of teen-oriented pop groups took over the airwaves. The emergence of the Backstreet Boys, N*Sync, 98 Degrees and others pushed the term into popular consciousness and their popularity coincided with a pop takeover that made household names out of Britney Spears, and N*Sync’s soon-to-be-alum Justin Timberlake. These boy bands were the brainchild of music managers (like the notorious Lou Pearlman), producers and labels who wanted to cash in on teen idol-dom--an entirely manufactured phenomenon, unlike R&B groups like Boyz II Men, who came together organically.

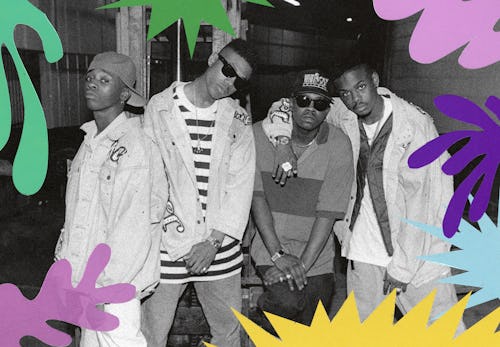

A Grammy-winning vocal quartet (now trio) from Philadelphia, Boyz II Men (Wanya Morris, Nate Morris (no relation), Shawn Stockman, and the erstwhile Mike McCrary) were and are an R&B group. At least that’s how I’ve always thought of them. Now, they’re considered a boy band, because boy bands grew from their influence. But re-centering R&B groups like Boyz II Men as simply forefathers to the more commodified genre that followed in their wake ignores a mountain of rich cultural history.

The R&B vocal group is a pillar of Black music. Led by stars like The Platters, the Drifters, and the Flamingos, doo-wop groups rose to prominence in the early 1950s. These groups were steeped in both rhythm & blues, traditional popular standards and gospel; harmony-driven, mostly Black and Latino, and especially popular in East Coast cities like New York, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. Out of the doo-wop tradition rose both pop acts like the Four Seasons and girl groups like the Chiffons and Crystals, as well as the soul groups introduced via 60s labels like Motown, Stax, and Philly International. The Temptations, Four Tops, Miracles, Delfonics, Dramatics, Spinners, O’Jays, and more came to define the soul era with their slick moves and dapper presentation.

But the appeal of teen idols has also been a part of popular music for decades. In the early 1970s, Motown’s Jackson 5 enjoyed tremendous commercial success and global appeal, with hit music dubbed “bubblegum soul.” The group’s blueprint was 50s doo-woppers Frankie Lymon & the Teenagers, and the J5 cultivated a mostly teenage audience. The Jackson 5’s image and approach was soon copied by former novelty act the Osmonds, also a family of teenaged brothers, but white and Mormon. And in the 1980s, a similar cycle emerged as the Boston based New Edition, a quintet in the Jackson 5 mold, rose to prominence with bubblegum R&B hits; only to see the all-white, also Beantown-based New Kids On the Block eclipse N.E. in chart success and visibility.

But in the wake of those groups, the term “boy band” became retroactively affixed to groups who’d emerged in the decades before the term was popularized. That retrospective refashioning of the term meant that now, groups like the Jackson 5 and New Edition were being dubbed “boy bands” as both an acknowledgment of their impact on what would eventually shape the early 00s pop wave and as a testament to the cultural dominance of that wave. The boy band phenomenon was so major that it caused commentators to rethink the past.

Groups from the 90s like Boyz II Men and Jodeci weren’t called “boy bands” by virtually anyone during their actual heydays. Such groups were initially dubbed “hip-hop doo wop” by some critics, as an acknowledgement of the R&B tradition that goes all the way back to groups of black teens singing on neighborhood corners in the 1940s. Jodeci, Boyz II Men, and similar groups weren’t just predecessors for white pop groups, they were the latest in a long Black male vocal tradition.

The tendency to frame 90s R&B groups as “boy bands” ignores the tradition they came from, and forever connects them to a more manufactured imitation that followed them. “Boy band” represents a whitewashed rebrand of the New Edition template; and it represents another way of obscuring Black art for white commerce. These groups, mostly born of a sense of tradition and community, are now being linked to groups not of that tradition or community — simply because boy bands were bigger. The lineage of Black music is imperative to how we should appraise Black music, not simply acknowledging its proximity to whiteness. When linking Black R&B groups to white boy bands with no regard for the history of such groups, it further obscures that lineage. A group like Boyz II Men’s influence on boy bands gets treated as more significant than their place as torchbearers for the Temptations.

“Boy bands” have a certain kind of specifically teenaged appeal; they tend to be marketed to young audiences. While it’s certainly true that Motown billed itself as the “Sound of Young America,” the Temptations and Four Tops aren’t exactly seen as teen idol groups. Nor are 70s Philly soul groups like the Spinners and the O’Jays seen as specifically teen-oriented acts. It’s important to always acknowledge the Black musical origins of boy bands, and by extension, the K-Pop phenomenon that has emerged in the wake of boy bands. But we should do so without feeling the need to revise Black music’s history to present R&B groups as part of a watered down version of the art they created.