In the middle of a crowded intersection in San Diego, a woman played a survival horror game at a pop-up stand. Confused and intrigued, I stopped to have a look. The game was The Final Exam, and the whole thing lasts a mere 10 minutes. You play as a high school student running from an active shooter and scrambling to find a place to hide within a tight time frame. If you don’t make it, the game tells you you’re one of 17,000 kids who are shot every year. If you do, you’re informed of legislative bills that, if passed in Congress, could help restrict the prevalence of these weapons.

The small, bite-sized experience is fairly bare bones, but no less harrowing for it. But what’s more fascinating is who made the game and why: The nonprofit, Change the Ref, in collaboration with a game developer, Webcore Games, wanted the world to know that violent games don’t cause real-life crimes — the prevalence of weapons do.

One of the very first issues raised on a federal level about video games was the question of whether playing violent games causes children to take up violent habits. The moral panic came to a head in 1993 and 1994 when Joe Lieberman led a number of hearings about violent video games. When talking about Night Trap, Sega’s B-Movie horror sleepover game, Lieberman said, “It ends with this attack scene on this woman in lingerie, in her bathroom. I know that the creator of the game said it was all meant to be a satire of Dracula, but nonetheless, I thought it sent out the wrong message."

The message is just the point in The Final Exam. The game turns this idea of moral influence on its head by using a video game to advocate for specific bills to get passed. Change the Ref was founded by Parkland shooting victim Joaquin Oliver’s parents, including his mother, Patricia Padauy-Oliver. (The Parkland shooting occurred in 2018 and is still considered the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history.)

“The entire world plays video games. So why are you going to tell me that the game is the problem?”

When Joaquin was alive, his mother remembers him being a fan of Call of Duty and sports video games like NBA 2K and FIFA. In many ways, it’s fitting that a video game is being used to pass on his message. Padauy-Oliver refutes the idea that video games cause shootings. While there are studies that show a connection between gaming and the way one approaches social networks, a link to violent public acts is ill-evidenced. Padauy-Oliver says that the issue is more about who has access to guns. She and her husband became advocates for weapons control following the tragedy.

“Every single country has people with mental health issues, but they don’t have guns right there, waiting for them to grab, and then do whatever craziness that can happen,” Padauy-Oliver told Inverse. “The entire world plays video games. So why are you going to tell me that the game is the problem? There’s no way I’m going to take that as an answer.”

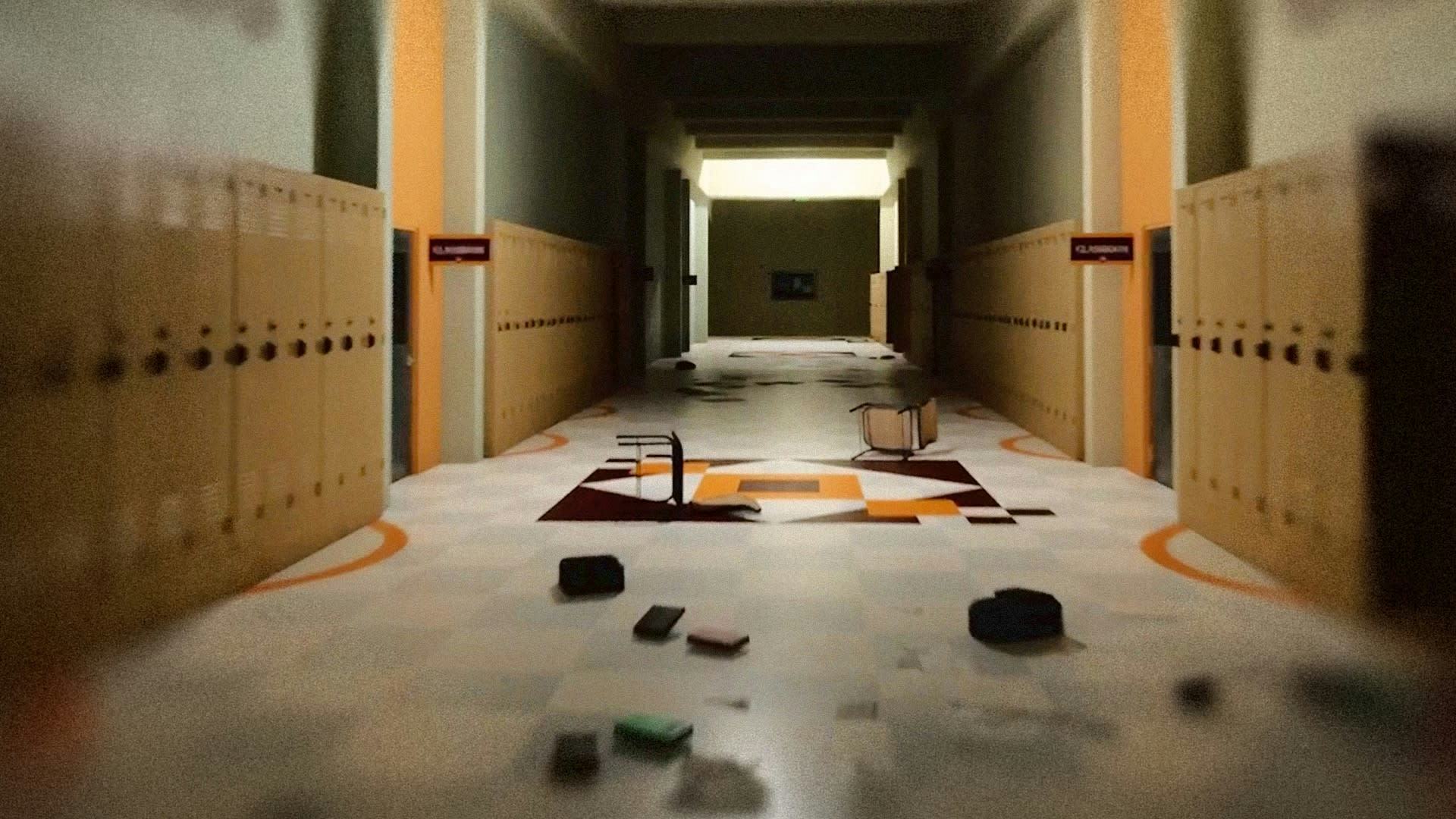

In The Final Exam, no gunshots are seen on camera, nor is there any explicit gore. Instead, there’s only the faint sense that time is running out and a gunman is on the loose; his movements erratic and unknown. There’s an eerie sense that you’re living the final moments of a high school student who is about to become a school shooting victim.

Making and promoting a game about school shootings hasn’t been easy.

“It’s very hard,” Padauy-Oliver says. “It’s really hard to do the job that I’m doing every day. To talk about Joaquin’s story, because I would love to talk about: Joaquin graduated, Joaquin having a girlfriend, Joaquin having a life. I would love to be sharing that instead of being here talking about why Joaquin is not here.”

Despite that difficulty, she knows this is something worth pursuing.

“But I cannot be threatened with those emotions because I need the strength to be talking to you, to present this game, to talk about this game to everyone that I can see.”