Concerns are being raised across the U.S. about whether schools have a right to compel female athletes to provide information about their menstrual cycles.

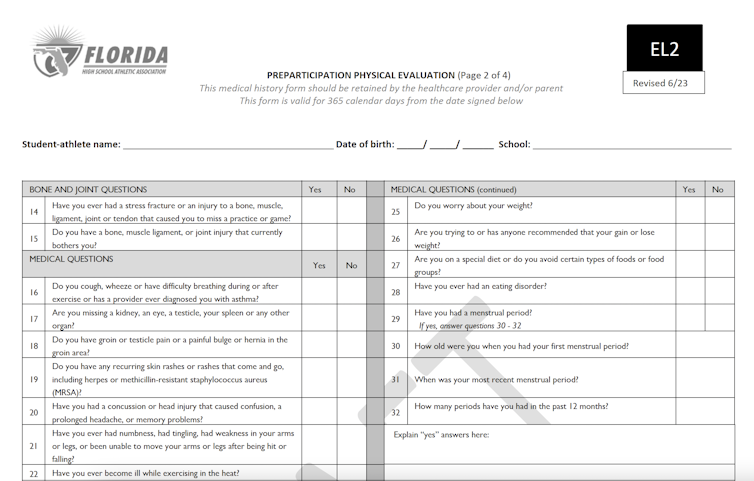

The Florida High School Athletic Association Board of Directors rejected a proposal in February 2023 that would have required high school girls to answer four questions about their menstrual cycles in order to play on school sports teams. The questions had previously been optional.

The four questions were: Have you had a menstrual cycle? How old were you when you had your first menstrual period? When was your most recent menstrual period? How many periods have you had in the past 12 months?

The answers, along with the rest of students' medical history, would have been entered into an online platform and stored on a third-party database called Aktivate. School personnel would have had access to this information.

While Florida decided to scrap the questions from their student forms, many states currently ask similar questions of their female athletes prior to participation in their sport.

As researchers who are experts in Title IX, sports and health care equity, and constitutional law, we have identified three reasons why schools and states tracking female athletes' menstrual history may conflict with federal laws.

1. It may violate federal anti-discrimination law

Title IX, a federal policy passed in 1972, prohibits federally funded schools from discriminating against students based on sex, sexual orientation or gender identity. The goal of the policy is to end sex discrimination, sex-based harassment and sexual violence in education.

While Title IX applies to all school settings, it is often most associated with athletics.

Requiring female student-athletes to submit menstrual cycle data to their schools could be a form of sex discrimination and therefore violate Title IX. The reason it is potentially discriminatory is because girls are the only students at risk of being denied the opportunity to play sports if they choose not to provide schools with details about their menstrual cycles.

In a 2020 Harvard Journal of Law and Gender study, three scholars argue that schools should create educational settings free of "unnecessary anxiety about the biological process of menstruation."

"Because menstruation is a biological process linked to female sex," they write, "educational deprivations connected with schools' treatment of menstruation should be understood as a violation of Title IX's core proposition."

2. It threatens constitutional rights

Tracking female athletes' menstrual history may be downright unconstitutional.

Forcing only females to disclose private medical information may violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits sex-based discrimination.

Also, 11 states have a "right to privacy" written into their state constitutions. For example, the Florida Constitution states that "all natural persons, female and male alike, are equal before the law and have inalienable rights," including "the right to be let alone and free from governmental intrusion into the person's private life."

While other states do not explicitly provide a right to privacy in their constitutions, legal precedent has determined that this right is implicit in the U.S. Constitution.

And finally, federal laws that protect medical and educational records do not have standards for maintaining medical records that are shared with schools and stored on third-party databases. This lack of precedent may result in privacy breaches.

3. It could be used against transgender students

The recent passage of several anti-LGBTQ+ policies in Florida made the Florida High School Athletic Association's attempts to track and digitally store menstrual data particularly worrisome to trans rights advocates.

In June 2021, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed a bill prohibiting trans girls from playing on girls athletic teams.

In March 2022, DeSantis signed the Parental Rights in Education bill, better known as the "Don't Say Gay" bill. It prohibits classroom instruction on sexual orientation and gender identity in K-3 public school classrooms.

And just one week after the proposed mandate was struck down, a Florida House committee advanced a bill that would place the Governor's office in control of the Florida High School Athletic Association.

As more states try to ban trans youth from receiving gender-affirming medical care – including hormone therapy, surgical procedures and other treatments – menstrual tracking in athletes could serve as another mechanism to harm and criminalize transgender youth.

Tracking menstrual cycles could "out" trans youth if they are required to disclose information about their menstrual cycle – whether that is the presence or absence of a cycle. If a school is responsible for outing trans kids, they violate both constitutional rights and Title IX policy, and they risk endangering the outed students' welfare.

Protecting period privacy

While the proposed Florida mandate was rejected, we have found that most states do in fact collect data on high school athletes' menstrual cycles.

Based on our collection of sports pre-participation forms, only four states – Mississippi, New Hampshire, New York and Oklahoma – as well as Washington, D.C., do not currently ask any questions about menstrual history on the sport pre-participation medical forms provided by their state athletic association.

Following the vote on the Florida proposal, three House Democrats introduced legislation called the Privacy in Education Regarding Individuals' Own Data Act, or PERIOD Act. It would prohibit schools from collecting menstrual information altogether.

If this legislation is adopted, the estimated 3 million American high school girls who play sports in a state that still asks about menstrual history will no longer have to share this information.

Lindsey Darvin, Assistant Professor of Sport Management, Syracuse University; David Schultz, Professor of Political Science, Hamline University , and Tia Spagnuolo, Doctoral Student in Community Research and Action, Binghamton University, State University of New York

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.