It was a sultry August weekend in 1988, but the participants at a specially convened conference in Washington, DC, weren’t hot under the collar about the weather. They were determined to take action against three serious threats to astronomy.

One problem was the amount of junk accumulating in orbit around the Earth: everything from defunct satellites to an astronaut’s glove. This space debris was a danger to new missions, including the Space Shuttle and the forthcoming International Space Station.

A second strand had a strong resonance with me personally, as my own research had relied on sensitive radio telescopes. Radio communications were booming, and these powerful transmissions were drowning out the faint whispers of radio waves coming from distant galaxies and quasars.

But it was the third threat that hit the headlines, both then and ever since: light pollution. The uncontrolled spread of night-time lighting was illuminating the sky and preventing both professional astronomers and casual stargazers from viewing the Universe in all its splendour.

American astronomer Dave Crawford led the campaign. Based at the National Optical Astronomy Observatory in Arizona, he and his colleagues were viewing a night sky that was aglow with stray light from nearby Tucson. Crawford founded the International Dark-Sky Association and rallied astronomers from around the world.

Inspired by the Washington meeting and by Crawford’s eloquence, British astronomers chose the fight against light pollution as our campaign for a National Astronomy Week in 1990, raising awareness in the UK for the first time through articles, broadcasts and a petition led by the astronomer royal.

Our theme was “light pollution is the only kind of pollution that costs nothing to clear up.” In fact, tackling light pollution saves money, as it reduces the amount of electricity we use. Recently, the International Dark-Sky Association has calculated that the USA wastes $2bn a year lighting up the sky; and researchers this side of the Atlantic have come up with a similar figure for Europe.

Environmentally, cutting light pollution makes sense too, not just by reducing the emission of carbon dioxide from power stations, but also because light pollution disrupts the lives of birds, bats, turtles and most other nocturnal species.

Britain’s Commission for Dark Skies carries on the campaign in the UK, and many local authorities around the country have got the message and are now controlling outdoor lighting. They have set up designated areas where lighting is restricted and dark skies are being preserved.

These are all approved by the International Dark-Sky Association, and fall into different categories. Dark sky reserves are large regions protected from light pollution, with a very dark core. Of 20 International Dark Sky Reserves worldwide, eight are located in these islands, ranging from Kerry to Snowdonia and the South Downs.

Among our four International Dark Sky Communities, Sark stands out: this small member of the Channel Islands bans public lighting and all motor vehicles apart from tractors. And we have eight medium-sized International Dark Sky Parks. They are scattered from Land’s End to the Cairngorms, where the Tomintoul and Glenlivet Dark Sky Park encompasses the Glenlivet distillery – convenient for those cloudy nights!

What’s up

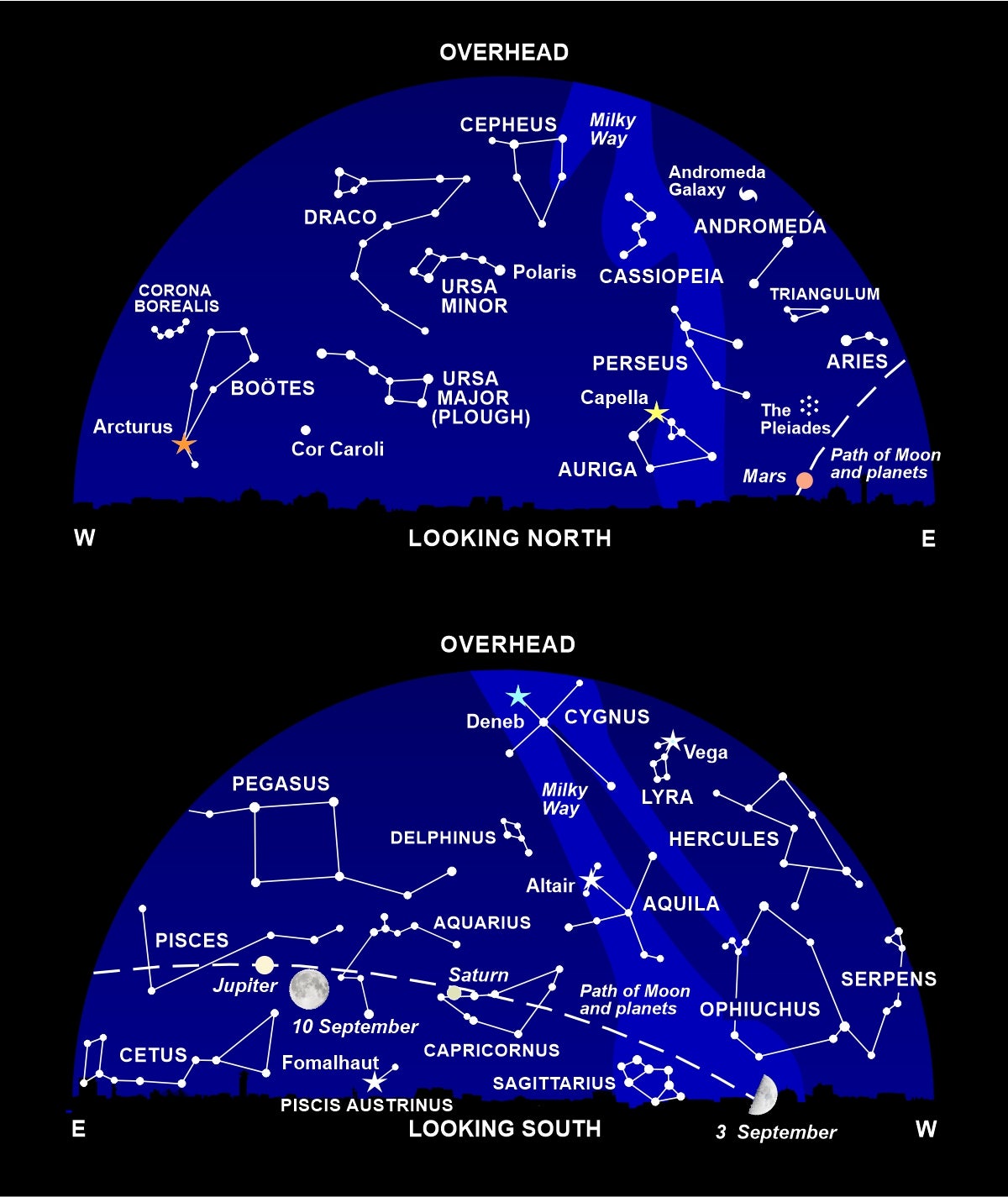

You can’t miss Jupiter this month, blazing all night long far more brilliantly than anything in the night sky bar the moon. The giant planet is at its closest to the Earth on 26 September, and opposite the sun in the sky. Grab a pair of binoculars to view Jupiter’s four largest moons, constantly changing their positions night by night as they orbit their parent world.

Above Jupiter lies a large square of stars, depicting the flying horse Pegasus, and higher still the bright stars Deneb and Vega. Over to the north, look out for the W-shape of the constellation Cassiopeia.

The bright “star” well to the right of Jupiter, and about the same height above the horizon, is the next world from the sun. Saturn is 20 times fainter than Jupiter, but still prominent as it currently lies in a region of faint stars.

Both these gas giant planets are a treat when you see them in a small telescope. As well as Jupiter’s major moons, you can make out the stripy clouds in the planet’s atmosphere and the Great Red Spot, a vast storm that may have been blowing for 300 years. Turn to Saturn for an unforgettable view of its magnificent rings.

I don’t usually mention the other two giants of the solar system in this column, as they are faint and hard to see, but 14 September is a golden opportunity to spot the seventh planet, Uranus, when the moon moves right in front of it. Uranus is just visible to the naked eye, but with the moon’s glare you’ll need binoculars to discern the faint world. Keep watch during the evening, and you’ll see Uranus disappear behind the moon at around 10.27pm (the exact time depends on your location) and reappear at about 11.20pm.

The most distant giant planet, Neptune, lies opposite the sun on 16 September, but you’ll need suitable software to locate the planet and binoculars or a telescope to see it.

Still on the planetary front, Mars is rising around 10pm in the northeast, while Venus appears after 5.30am as the glorious morning star.

Diary

3 September, 7.08pm: first quarter moon near Antares

8 September: moon near Saturn

10 September, 10.59am: full moon

11 September: moon near Jupiter

14 September: moon occults Uranus

15 September, before dawn: moon near the Pleiades

16 September: Neptune opposition; moon near Mars and Aldebaran

17 September, 10.52pm: last quarter moon

23 September, 2.04am: autumn Equinox

25 September, 10.54pm: new moon

26 September: Jupiter at opposition

30 September: moon near Antares

Nigel Henbest is a passionate opponent of light pollution. A founder member of the International Dark-Sky Association and Chairman of National Astronomy Week 1990, his latest book – ‘Philip’s 2023 Stargazing’ (Philip’s £6.99) – details all the dark sky locations in Great Britain and Ireland.