From 1936 to 1939, the Spanish civil war divided neighbours, friends and families, and people both inside and outside Spain kept a close eye on what was happening in the country.

Two of the best-known international figures who, through their images and writings, managed to convey what was happening in Spain were the war photographer Robert Capa and the writer Ernest Hemingway.

There was also a personal closeness between them that impacted their work. In fact, Capa’s photographs served as inspiration for Hemingway’s writings.

Ernest Hemingway: a correspondent committed to the Republic

Hemingway, who had a previous connection with Spain, was a well known writer when he decided to return to journalism to cover the Spanish conflict for the North American Newspapers Alliance (NANA).

Hemingway’s stay during the war resulted in thirty dispatches for the American press and one more, with greater personal involvement, published in the Soviet newspaper Pravda. He also found time to describe Spanish society in writings centred on everyday life. His public image as an intrepid reporter was helped by the fact that he was, at the time, one of the best known correspondents in the world, and one of the best paid.

In time, his work expanded beyond dispatches from the Spanish Civil War to include one of his best known works: For Whom the Bell Tolls. Drawing on a combination of real life experiences and fictional content, the Nobel Prize laureate conveyed his impassioned vision in defence of the Republican cause and the Spanish people.

Hemingway’s novel came to symbolise the Spanish conflict in the collective imagination. This was amplified by the film of the same name, starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman, which garnered nine Oscar nominations.

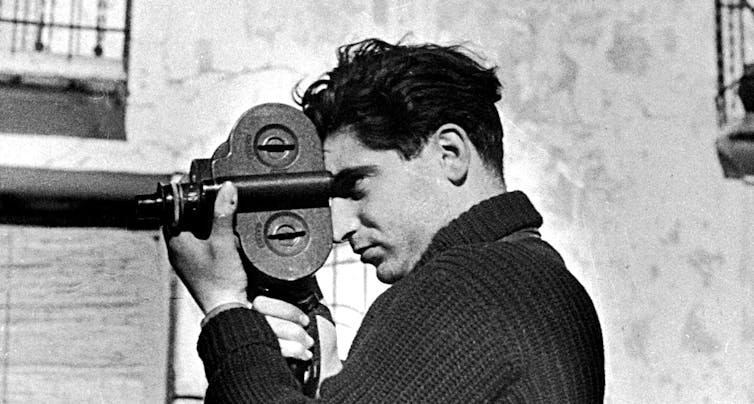

Robert Capa: an intrepid, influential photographer

Robert Capa’s images often capture what Henri Cartier-Bresson called the “decisive momnent”, meaning the culmination or apex of the event being photographed. In his photographs, the mid ground predominates, eschewing either general panoramas or minute details, with depersonalised subjects and gestures presented in stark black and white. His images are often grainy and lacking in sharpness, lending them an unique atmosphere.

Capa photographed several conflicts, including the Normandy landings. These photos are notable for their proximity to the events, which the images narrate with great clarity.

These images of D-Day inspired a similar visual language in Steven Spielberg’s film Saving Private Ryan. This is especially evident in the opening Normandy landing scene, where the aesthetic helps to create an unreal and unsettling atmosphere, mainly due to the grain of the film and the slight blurring that characterised Capa’s work.

However, Capa is most well known for his work in the Spanish Civil War. It should be noted that Robert Capa was a pseudonym adopted in 1936 – Capa’s birth name was Endré Ernö Friedmann. In addition to Capa himself, two others had previously published work under this name: his partner, Gerda Taro, who created the pseudonym and died on the Brunete front in 1937, and David Seymour (nicknamed Chim). Once Capa was the only one using this assumed name he began to publish his first reports in the pages of the magazine Vu , almost from the very beginning of the war. Subsequently, other publications such as Regards, Ce Soir and the British magazine Picture Post began to publish his output.

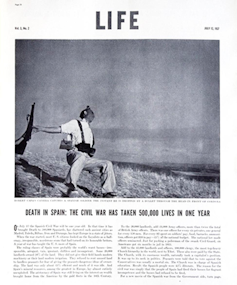

The Falling Soldier: an iconic photo mired in controversy

Although The Falling Soldier, one of Capa’s best-known photographs, was published in French magazines in 1936, it did not reach international fame until it appeared in Life in July 1937.

It is undoubtedly one of the most widely published images of the conflict, but the circumstances surrounding this photograph – taken at the height of the conflict – have contributed to controversy over its authenticity. Its veracity has been defended by, among others, his official biographer, Richard Whelan. In a January 1999 interview with El País semanal, Wheelan stated:

“The controversy has been definitively cleared up in Capa’s favour thanks to the discovery of the identity of the man in the photograph, Federico Borrell García, who was killed in Cerro Muriano, 12 kilometres north of Córdoba, on 5 September 1936.”

While not wishing to undermine the photo’s symbolic value, one of Professor José Manuel Susperregui’s investigations has deepened the controversy by relocating, on the basis of an topographic study, The Falling Soldier to Cerro del Cuco instead of Cerro Muriano.

His study concludes by stating that:

“This new information on location completely changes the reading of The Falling Soldier, and demonstrates that the author’s own version of this photograph is totally false, dismantling the various accounts based on his version of events. Additionally, other theories attribute its authorship to his companion Gerda Taro.”

Regardless of its authenticity, the image’s value is indisputable and enduring. Not only is it one of Robert Capa’s most popular photographs, it is also the best known photograph of the Spanish Civil War and one of the most famous war photos ever. It also set a precedent for spontaneity and action war photography.

The physical and intellectual proximity of foreign correspondents and Spanish journalists in the Civil War led to ideologically charged photographs and reports, which arguably bordered on propaganda, often enhanced by the name on the byline. In their new narrative perspective, civilians and anonymous people became the protagonists of war images. In the same way, everyday life was also brought into reporting.

Capa’s Falling Soldier and Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls are all but synonymous with the Spanish Civil War. Both works, much like their authors, have become emblematic of the Republican cause.

Miguel Ángel de Santiago Mateos no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.