The curious thing about Soviet brutalist architecture is that it is incredibly rich in profoundly photogenic buildings that appear simultaneously utopian in their conception and intent and distinctly dystopian in their dilapidated states of disrepair.

Soviet brutalist architecture explored

The brutalist architecture of the Soviet era has found itself fetishised in publishing and across social media and succumbing to the indignity of apparently inspiring AI to create machine hallucinations feeding off their visual vocabulary. Everything from publisher Fuel’s counterintuitively successful Soviet Bus Stops (now also a film) to massive coffee table brutalist blockbusters (the spectacular photos of Frédéric Chaubin, in particular) and their occasional appearance in the backgrounds of movies and photoshoots has created a kind of cult.

But it is based solely on the image; these remarkable buildings represent a very different moment, a late burst of optimism in socialism expressed through architecture. What, exactly, do these buildings mean? And how did they come about in such numbers and become neglected so quickly?

Soviet brutalism: the history

To understand a little, you need to read the rapid waves of change from the revolutionary architecture of the Constructivists in the 1920s, who managed to build only a small number of (albeit deeply influential) structures, and their repression by Stalin in the 1930s in favour of a stolid, hypertrophied classicism. That, in turn, gave way after Nikita Krushchev’s accession in 1953 to a concentration on addressing the huge Soviet housing problem, the construction of millions of units of mostly panel blocks over the following decades.

It was with Leonid Brezhnev’s coming to power in 1964 (he served as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union till 1982) that the focus shifted to the many, vast regions of the country with a certain loosening of central control; and they, in turn, began to express emerging modern identities through architecture. At the same time, the sci-fi era had taken hold, first with the success of Sputnik and then with widespread scientific development in everything from nuclear power to virology, a new reliance on technology and a faith in the future expressed through fiction and film. There was also, contrary to the myth of a closed society, considerable exchange between East and West, with Soviet architects being well aware of the emergence of brutalism elsewhere in Europe.

Yet the Soviets developed their own remarkable genres, using expressive, sculptural language to mould a new architecture. Some of the results have become familiar. The UFO-machine gear of the Druzhba Sanatorium overlooking the beach in Yalta (Igor Vasilevsky, 1983) was so odd that the Pentagon mistook it for a new rocket launch pad. It now adorns the covers of dozens of brutalist books and regularly pops up in Instagram feeds. And the Ministry of Highway Construction in Tbilisi (George Chakhava, 1975) is an 18-storey series of interlocking blocks that can look bizarrely contemporary, even though it was completed half a century ago.

Another UFO landed in a street in Kyiv in the form of the Ukrainian Institute of Scientific and Technological Research and Development (Lev Novikov and Florian Turiev, 1971). Then there is the Polytechnic Institute of Minsk in Belarus (Igor Esman and Viktor Anikin, 1983), a space-age battleship of a building with what looks like ski slopes. These experiments illustrate the efforts across the Socialist republics to develop their own aesthetic identities.

This was also often done through the invention of wholly new building types, socialist equivalents to the cathedrals of the past. There were wedding palaces such as Tbilisi’s castle-like Palace of Ceremonies (Victor Djorbenadze, 1984) and funerary centres like the same architect's Mukhatgverdi Ceremonial Hall (also Tbilisi, 1974, and now itself looking more than a little corpse-like) and the strange, haunting Park of Memory in Kyiv (Avraam Miletskyi, Volodomyr Melnychnko and Ada Rybachuk, 1980).

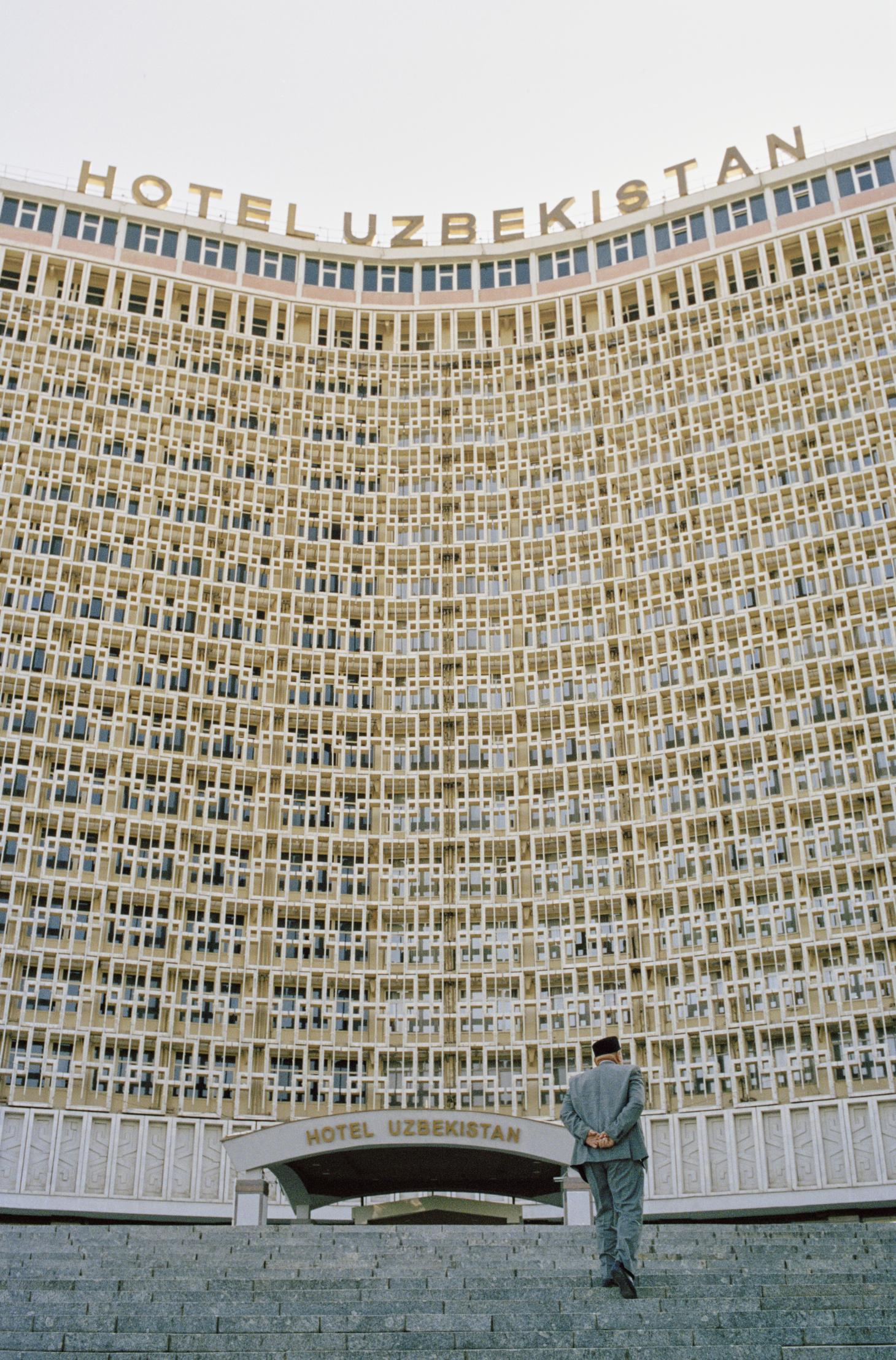

Then there was a raft of memorials: powerful, theatrical gestures glorifying Soviet efforts in war, in space, in science or in ‘friendship’ with many other nations. There were also circuses (and circuses were very big in the USSR), tributes to tents reimagined in massive concrete, ‘Palaces of the Republic’, ‘Palaces of Sports’ and ‘Palaces of Lenin’, in fact, palaces for the people everywhere.

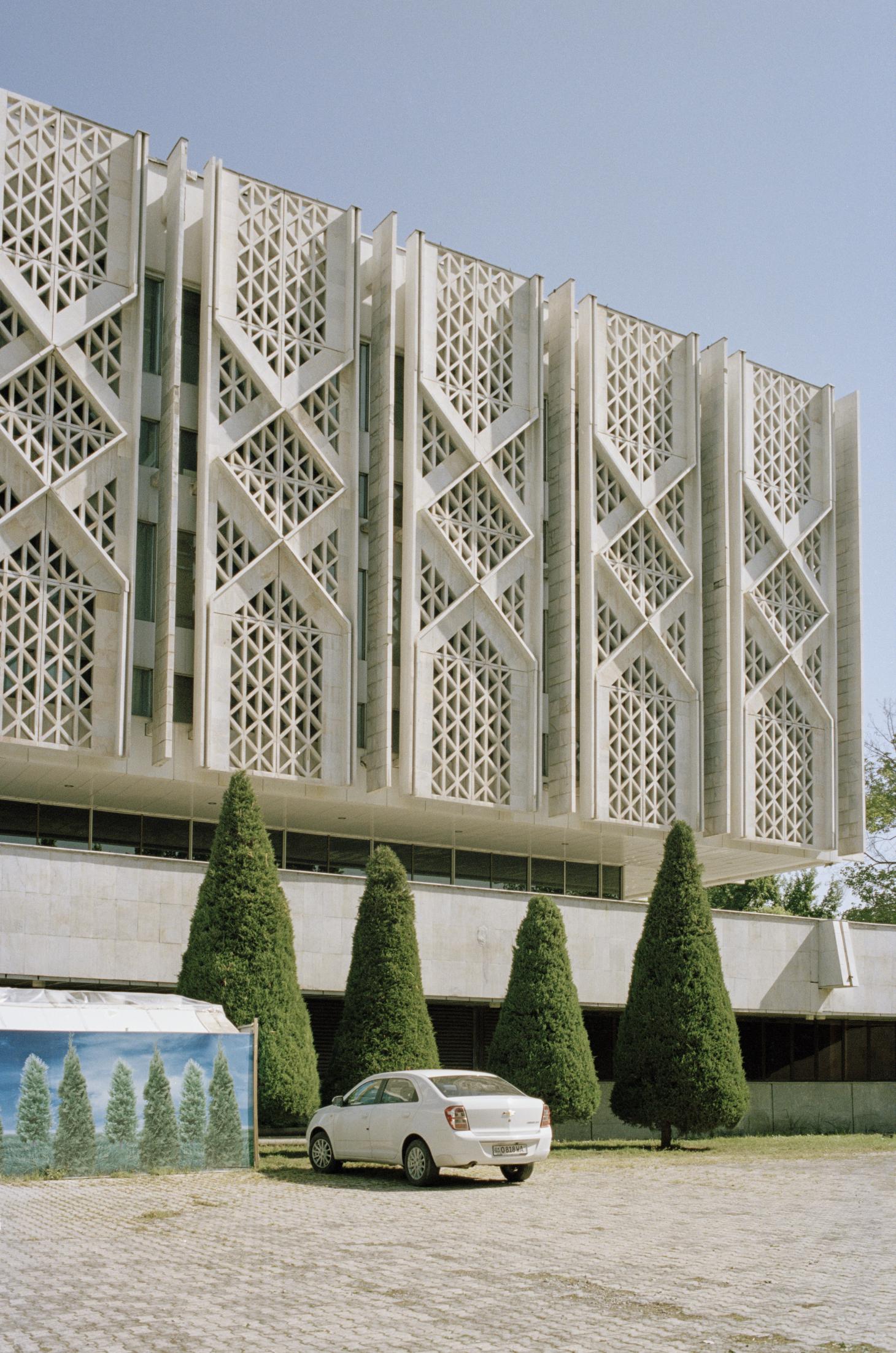

Some of these proletarian palaces also began to display intriguing inflexions, uncharacteristic of Western brutalism. The Peoples’ Friendship Palace in Tashkent (Yevgeny Rozanov, 1981) has hints of Islamic architecture, for instance; the Exhibition Hall of the Uzbek Union of Artists in the same city (R Khayrutdinov and F Tursunov, 1974), yet more so, with ogee arches and a façade like a carpet.

The expansion of holiday provision created yet more opportunities for architectural expression. The gorgeous cantilevered extension of the Union of Writers summer resort in Sevan (Gevorg Kochar, 1969) is an old favourite and the once derelict and now chi-chi Baltic Beach Hotel in Jurmala, Latvia (Normunds Pavārs, Viktors Valgums and Modris Ģelzis, 1981), with its staggered levels like a liner, remains remarkable.

Although the republics were keen to use architecture to express their burgeoning identities within the USSR, there was plenty going on in Moscow and the rest of Russia too, much of it dedicated to celebrating science, the atheist state’s religion. The astonishing bulk of the Atomic Engineers’ Building acts like a scientific city wall and the Russian State Scientific Centre for Robotics and Cybernetics (Boris Artyushin and Stanislav Savin, 1986) was a true cathedral of science, designed in the early 1970s but only completed a few years before the regime ran out of cash and Gorbachev ended it all. The slow pace of Soviet construction, a shortage of materials and labour and not a little corruption meant that brutalism flourished later here than it did elsewhere, well into the 1980s.

These sculptural spectacles, most of which survive in varying states of decay, bridged the visionary experiments of Constructivism with the more modern statement buildings used to build regional and metropolitan identity. From the most modest of bus stops to the most grandiose megablocks, they remain the representatives of a remarkable moment in which architecture’s capacity to define a place and accommodate genuine public participation was taken seriously. Many of the finest examples remain in a precarious position, crumbling and unloved, despite their global appeal and now is the time to save them.