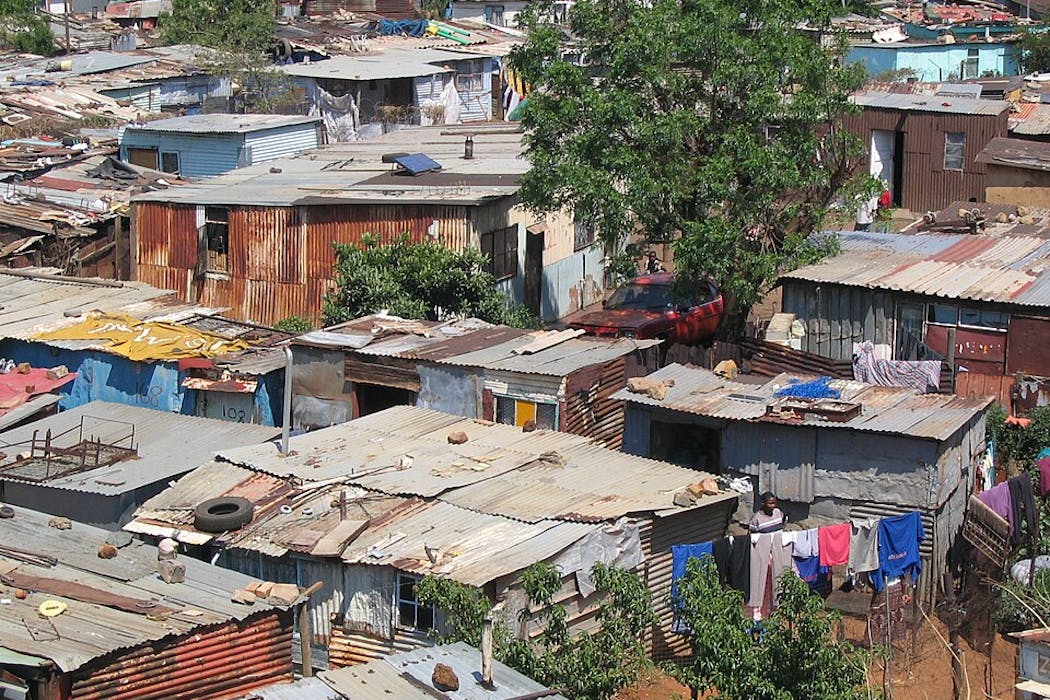

“Turn right after the first big tree; my house is the one with the yellow door.” In parts of South Africa, where settlements have grown without formal urban planning due to rapid urbanisation, that could well be a person’s “address”.

Having an address has many purposes. Not only does it allow you to find a place or person you want to visit, it’s compulsory in South Africa to provide an address when opening a bank account and registering as a voter in elections. Address locations are used to plan the delivery of services such as electricity or refuse removal and health services at clinics or education at schools. Police and health workers need addresses in emergencies.

Nowadays, address data is integrated and maintained in databases at municipalities, banks and utility providers, and used to analyse targeted interventions and developmental outcomes. Examples would be tracking the spread of communicable diseases, voter registration or service delivery trends.

South Africa has had national address standards since 2009 to make it easier to assign addresses that work in multiple systems, and to share the data. But the standards are not enforced, so the struggle with addressing persists. There is still no authoritative register of addresses in South Africa, and it’s not clear who is responsible for the governance of address data.

We work in geography and geoinformatics, an interdisciplinary field to do with collecting, managing and analysing geographical information. We recently turned to a neglected source to explore the issue of addresses: the people in government and business who actually use the information. We wanted to explore what they said about whose job it is to give everyone an address, how the data is maintained and what’s standing in the way of doing this.

Our research took a qualitative approach. We interviewed stakeholders to get their unique insights and daily experiences about what addresses are used for, how they are used, challenges that are experienced and how these are overcome. We spoke to 21 respondents across different levels of government with in-depth experience of projects, in both urban and rural settlements, as well as private companies that collect, integrate and provide address data and related services.

Our main finding was that there’s no clear vision of future address systems, or leadership on the issue. Without agreement on whether there is a problem, or whose problem it is, a resolution isn’t possible.

Categories of addresses

First we collected all the different purposes of addresses and systematically categorised them. The main categories were:

finding an object (for example, for postal deliveries)

service delivery (such as electricity)

identity (for example, for citizenship)

common reference (for example, use in a voter register or in a pandemic).

The broad spectrum of address purposes suggests that addresses are essential to society, governance and the economy in a modern world.

So what’s standing in the way of better address coverage?

Need for governance: The interviews confirmed that stakeholders need clear rules, regulations, processes and structures to guide decisions, allocate resources and ensure accountability about addresses and address data. Most of the respondents considered addresses to be necessary for socio-economic development.

Read more: 'Walk straight': how small-town residents navigate without street signs and names

Leadership: These responses suggest that the societal problem of addressing is not (yet) clearly identified and defined. That makes it difficult to determine who should legitimately resolve the problem, for whom and how.

Interviewees raised concerns about leadership and vision at different levels of government affecting the country’s ability to solve the address issue. They agreed that the task had not been assigned to municipalities, which have many other pressing priorities and limited resources. The South African Post Office could play a role. But it has been placed in business rescue.

Adapting to gaps: In this constrained environment, stakeholders resort to short-term “fixes” that don’t have systemic impact. For example, some municipalities assign numbers to dwellings based on aerial photography, or barcodes on dwellings, or only locate the main assembly points in their jurisdiction, to fulfil their own responsibilities. So nothing changes: addresses and address data are incomplete and of poor quality.

Respondents also made suggestions.

Some questioned whether addresses were needed at all. They said there were other ways of finding a house or a business, such as navigating to a coordinate shared via Google Maps, or using verbal directions.

Some suggested that the uncertainty about responsibilities could be an opportunity for the private sector. It is already collecting address information from various sources like municipalities, then standardising, integrating and making available address data and related services, at a cost.

However, as is the case with many other services in the country, rural areas may be left behind where there is no economic incentive. Access to private data becomes unaffordable for government and society at large.

Ending the aimlessness

The deficiencies and adaptations in South Africa suggest that addressing is in a state of aimlessness.

How to fix the problem will require a number of interventions.

Firstly, there need to be decisions, actions and institutional commitments towards long-term strategies that will stop the drift. For example, cities and municipalities should strive for full coverage of addresses. They should also improve the quality and standardisation of the data, so that they are more useful.

Secondly, there’s a need for innovation and investment to transform and strengthen the governance of the country’s addressing infrastructure. For example, the European Commission recommends e-government based on a set of interlinked registers for property, addresses, people, business and vehicles.

Thirdly, data collection platforms and databases should be designed with the understanding that different types of addresses are in use – it could be a street name and number, or an informal description. Different types of addresses should have equal validity or credibility.

Read more: South Africa needs a national database of addresses: how it could be done

At a more technical level, address metadata (information about the data) should make it possible for different systems to use it.

Addresses connect us to society – locally to our community and globally to the rest of the world. Addresses are essential for socio-economic growth and good governance in cities and municipalities.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.