Days into COP28 in Dubai, one little-known archipelago has come into sharp relief: Socotra. Composed of four small Yemeni islands, Socotra has been in the sights of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) ever since the civil war in Yemen erupted in September 2014. The UAE has been part of the Saudi-led coalition – backed logistically by the United States – against the Iran-aligned Houthi rebels since March 2015, but Socotra has been spared by the civil war and Houthis thus far.

One of the world’s most biodiverse islands

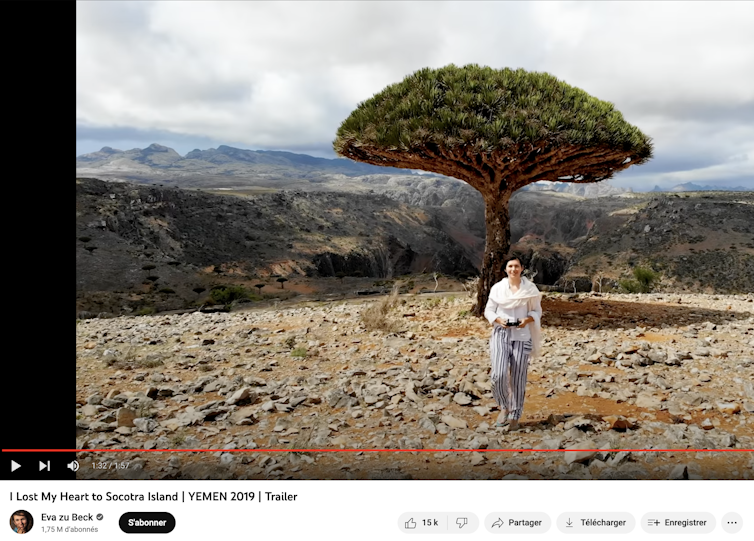

Known for its unique and abundant wildlife, Socotra was believed to be the original location of the Garden of Eden. The archipelago is listed as a Unesco World Heritage site to protect what is considered one of the world’s most biodiverse and distinctive islands. Naturalists and environmentalists estimate that 37% of 825 plant species 90% of its reptiles and 95% of its land snails exist nowhere else in the world.

The archipelago is increasingly in the UAE’s sights because of its strategic location between the navigable waterways of the Gulf, Africa and Asia. It’s a potential linchpin for shipping, logistics and military defence or projection, and could allow the UAE to advance their geostrategic goals while countering those of competitors and adversaries. The Emirates are also thought to be eyeing Socotra for its touristic development potential and this would represent a sure threat to the archipelago’s biodiversity. But how real are these scenarios?

Old Emirati ties

It would be easy to frame UAE’s influence in Socotra in terms of “intrusion”. Such a narrative, however, glosses over the Socotrans’ and Emiratis’ historic ties, which long predate the war. In the late 1950s, before the oil was discovered in Abu Dhabi, some Emiratis – especially traders from Ajman – migrated to the island while, conversely, many Socotrans settled in the sheikhdoms in the ‘60s for work.

Currently, about 30% of Socotra’s population live in the UAE, above all north of Dubai in Ajman emirate. The UAE has strengthened its economic, military and cultural influence in the archipelago, all while Socotra Island underwent deep social change following its special conservation status decreed in 2000 by the United Nations. Known as Soqotra’s Conservation Zoning Plan, the new binding environmental regime effectively turned the island into a national park and placed it under the international supervision. The Arab Spring also spread to its capital in 2011, inspiring locals to rise against Yemen’s president Ali Abdullah Saleh. The Emiratis took advantage of this period of instability to weave patronage networks.

The Emirati presence has therefore accelerated the politicisation and militarisation of Socotra. Nevertheless, Socotra is still being studied mostly through the lenses of environmentalists and anthropologists, rather than of political scientists and security experts. This makes it difficult to obtain reliable information on the archipelago’s political and military make-up.

From isolation to political awareness

In Socotra’s history, the issue of being ruled from the outside has always been a powerful topos, probably due to its geographical remoteness. The 2011 Yemeni uprising encouraged debate about autonomy among islanders and, later, the rise of the Emirati presence in the archipelago has boosted fears of foreign interference.

In 2011-12, protests in Hadiboh, the island’s largest town – remarkably recounted by the anthropologist Nathalie Peutz – echoed the slogans heard in the Yemeni cities of Sana’a and Taiz calling for political reform and the end of the regime and its corruption. Internet access has since been on the rise, with locals shifting into two camps: those claiming for a Socotran governorate, and those demanding autonomy from the central government. Little by little, political awareness took root. Competing councils opposed official authorities, perceived as corrupt and inefficient: these councils mirrored the party politics’ divisions of the mainland. In 2013, Socotra became a governorate on its own, since it was previously under the administrative authority of Hadhramawt (Eastern Yemen) and, before, the Southern port city of Aden.

Then the archipelago was struck by a series of cyclones, Chapala and Megh in 2015 and Mekunu in 2018, wreaking havoc on the island’s infrastructure and nature. In response, the Emiratis rebuilt mosques, created a water network and established the Shaykh Zayed City with education and health facilities. They also rebuilt the port of Hadiboh and the airport.

The pattern wasn’t new: in the Southern regions of Yemen, the UAE had already established considerable influence in the port cities of Mokha, Aden and Mukalla, operating and expanding infrastructures. By doing so, the Emiratis capitalised on patronage ties with Southern groups and militias, mostly linked to the pro-secessionist and UAE-backed Southern Transitional Council (STC). Reconstruction in Socotra has intertwined with commercial and tourism-oriented initiatives, with weekly flights now linking Abu Dhabi to Hadiboh.

Emirati and Saudi boots

The deployment of Emirati troops and armoured vehicles in Socotra in 2018 was a watershed moment for the island. Deployment occurred without coordination with local authorities, still loyal to the internationally recognised government. According to Emirati officials, the UAE sent troops to “support [Socotra’s residents], in stability, health care, education, and living conditions”. Many locals, especially from Muslim Brotherhood’s sympathisers opposed to the UAE, protested, urging for their removal. Seeking to resolve the situation, Socotra’s authorities arranged for the mediation of Saudi Arabia. The Riyadh-brokered compromise resulted into the Emirati withdrawal of most forces and equipment from the island.

But in coordination with the local governor, Saudi Arabia sent soldiers to Socotra on a “training and support mission” for Yemeni forces and to operate the port and airport. Moreover, the Saudi agreement included comprehensive “development and relief” for Socotra, revealing that the kingdom had its own development projects. Because of local divisions and foreign interference, the mainland tussle between Yemen’ pro-government forces (backed by Saudi Arabia) and the STC (supported by the UAE and secessionist interests) reached the island.

Since 2019, the STC increased its presence on the island, with fighters mostly coming from Aden and the Southwest. According to other sources, however, locals are trained by the UAE in Aden and then deployed in Socotra as part of the Emirati-backed and pro-STC “Security Belt Forces”.

UAE flags fluttering at check points

In 2020, after Socotra’s governor opposed the establishment of a local pro-Emirati elite force, the STC finally took control of the island, prompting Saudi forces to quickly withdraw. A de facto coup by the STC, it allowed the Emiratis to indirectly control the island, with the wages of Socotran civil servants reportedly paid by the UAE, and a unit of the local Coast Guard pledging its allegiance. An AFP report from 2021 also describes that “the STC’s banners are dwarfed by far larger UAE flags fluttering at police checkpoints”, while newly erected communication masts link phones directly to UAE networks rather than Yemen.

Much indicates that the island has undergone extensive militarisation. In April 2019, reports emerged that the UAE was building a military base on the island, close to the rebuilt Hawlaf port.

In 2020, Ahmed Nagi, one of the few political researchers able to visit Socotra recently, wrote “the island has become a regional football”. For analysts working abroad, information mainly comes from UAE media outlets aligned with the government, or from media linked to UAE’s regional rivals. As long as reliable information on political and military issues in Socotra remains scarce, analysts continue to have a hard time assessing the impact of “development” and “foreign intervention” on the region’s Garden of Eden.

Eleonora Ardemagni ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.