SOARING oil and gas revenues from the North Sea could give arguments for Scottish independence a “boost”, experts have said.

Economics professors Stuart McIntyre and Graeme Roy, of Strathclyde and Glasgow Universities respectively, said that there had been a “dramatic turnaround” in energy prices following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which would see receipts from the North Sea skyrocket.

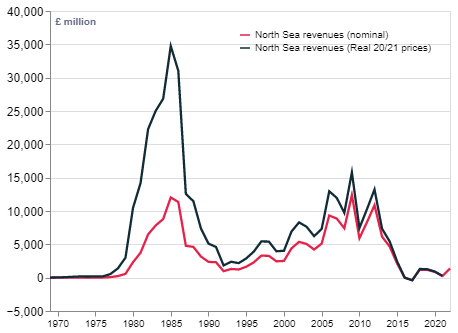

Writing for The Economics Observatory, the professors noted that “North Sea revenues jumped from just £500 million in 2020/21 to £3.2 billion in 2021/22”.

“In their March 2022 forecast, the OBR [Office for Budget Responsibility] projected that North Sea revenues could rise further to £7.8 billion in 2022/23.”

They note that an impending recession would have its impacts spread across the whole of the UK, whereas the “key beneficial public finance effects – oil and gas revenues – will be concentrated in Scotland”.

The total revenues for 2022/2023 are expected to “jump to levels not seen in over a decade”.

Their analysis goes on: “The Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) estimates that oil and gas revenues would need to total around £14.5 billion this year for the Scottish implicit deficit to match that of the UK as a whole. They conclude that ‘such a figure is plausible, and may be exceeded’.”

Commenting in August after the publication of the annual GERS figures, the IFS noted that Scotland’s “underlying public finances are set to significantly further improve this year, 2022-23, again driven by surging North Sea oil and gas revenues”.

The institute’s associate director, David Phillips, noted that the timing of the 2023 GERS figures, coming just two months before the SNP’s planned second independence referendum, could be “fortuitous” for the Yes movement.

However, Phillips, McIntyre, and Roy all state that the boost to Scotland’s finances from soaring revenues from North Sea oil and gas will only be in the “short term”, and an independent Scotland will need to develop its economy in other ways.

McIntyre and Roy wrote: “It is important to note that the long-term trend for oil and gas revenues is for a phased decline. Oil and gas production peaked in 1999 and remaining reserves are now in more challenging and costly areas of the North Sea.

“At the same time, governments – including the Scottish Government, in which the Green Party holds two ministerial positions – are committed to the transition from fossil fuels to renewable forms of energy, with the objective of reaching net-zero carbon emissions.”

They add: “Scotland – like many other countries – faces important long-term fiscal challenges associated with an ageing population and rising healthcare spending. Whether constitutional change will make these challenges easier or harder to solve is likely to be a key fault-line in any future debate on Scottish independence.”

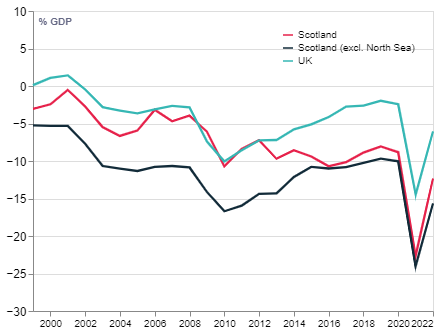

This year’s GERS figures estimated that Scotland’s budget deficit had fallen from 22.7% of GDP in 2020/21 to 12.3% of GDP in 2021/22. This was a more rapid fall than the UK as a whole, which saw its deficit fall from 14.5% of GDP in 2020/21 to 6.1% of GDP the following year.

McIntyre and Roy said a “key reason for this relatively ‘better’ performance in Scotland was the increase in the value of North Sea oil and gas output and revenues”. Phillips went one further, saying the increase in revenues was “entirely” to thank.

McIntyre and Roy noted of GERS: “In most years, Scotland is estimated to have a weaker position than the UK as a whole – largely driven by higher spending per head – but this relative gap is closed (and even eliminated on occasion) when oil revenues are included.”

The economics professors also said of the skyrocketing energy prices: “Oil prices increased from $18.38 per barrel in April 2021 to $117.25 in March 2022. Over the same period, gas prices rose from £0.55 per therm to £3.14.”

Edit: Professor Stuart McIntyre works at the University of Strathclyde, not the University of Stirling as this story originally and erroneously stated.