Imagine growing up beside the eastern Mediterranean Sea 14,000 years ago. You’re an accomplished sailor of the small watercraft you and your fellow villagers make, and you live off both the sea and the land.

But times have been difficult — there just isn’t the same amount of game or fish around as when you were a child. Maybe it’s time to look elsewhere for food.

Now imagine going farther than ever before in your little boat, accompanied maybe by a few others, when suddenly you spot something on the horizon. Is that an island?

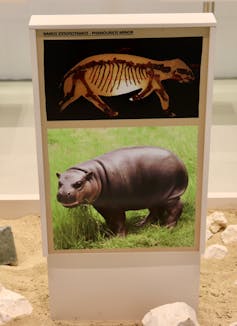

An island of tiny elephants and hippos

Welcome to Cyprus as the world emerges from the last ice age. You are the first human to set your eyes on this huge, heavily forested island teeming with food.

When you beach your boat to have a look around, you can’t believe what you’re seeing — tiny boar-sized hippos and horse-sized elephants that look like babies to your eyes. There are so many of them, and you’re hungry after the long journey.

The diminutive beasts don’t seem to show any fear. You easily kill a few and preserve the meat as best you can for the long journey back.

When you get home, you are excited to let everyone in the village know what you’ve found. Soon enough, you organise a major expedition back to the island.

Of course, we’ll never know if this kind of scenario took place, but it’s a plausible story of how and when the first humans managed to get to Cyprus. It also illustrates how they might have quickly brought about the demise of the tiny hippopotamus Phanourios minor, as well as the dwarf elephant Palaeoloxodon cypriotes.

Dwarf ‘giants’

Cyprus wasn’t the only Mediterranean island with dwarf wildlife. In fact, Crete, Malta, Sicily, Sardinia and many other islands had their own dwarf elephants and hippos.

Island dwarfism — the process in which a once large, mainland species evolves to become smaller in response to fewer resources and predators — is in fact quite common. Unfortunately, the process also makes such species more vulnerable to rapid environmental change, including the arrival of new predators such as humans.

The Cypriot dwarf hippopotamus was the smallest dwarf hippo in the Mediterranean region. Genetic data suggest it diverged from the common hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius) roughly 1.5 million years ago.

The Cypriot dwarf elephant was less than 10% of the size of its mainland ancestor, the straight-tusked elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus) that inhabited Europe and Western Asia during the Middle and Late Pleistocene.

An extinction controversy

For a long time, many archaeologists and palaeontologists didn’t believe humans had anything to do with the extinction of these two “megafauna” species on Cyprus.

The doubters assumed that either people arrived well after the extinctions, or the earliest humans were too few to be able to kill off entire species.

Earlier this year we showed that people came to Cyprus between 14,000 and 13,000 years ago, well before hippos and elephants went extinct. We also showed that the human population likely grew to several thousand within a few hundred years of arrival. But we didn’t know whether this human population was large enough to drive the dwarf hippos and elephants to extinction.

Our new research published today answers this question with a combination of several different types of mathematical models.

Read more: Humans are not off the hook for extinctions of large herbivores – then or now

Could a small human population cause extinction?

Even though these animals are long extinct, we can draw some conclusions about their likely population because we can estimate their weights from palaeontological information. The dwarf hippo weighed around 130kg, and the dwarf elephant came in at just over 500kg.

We also know how to translate weights to estimates of population size, longevity, survival and fertility. We can even use data collected from related species still living today, such as the pygmy hippo and the African elephant, to estimate how fast they would have grown.

With this information, we built computer models of what would have happened to the two mini-megafauna species on Cyprus when human hunters arrived. We estimated how efficient human hunters would be, how long it would take them to process each carcass, and how much energy hunter-gatherers need to survive.

We also estimated how much of the human diet included these species, and how this proportion might have changed as the dwarf hippo and elephant numbers dwindled.

We found that even a small human population, numbering between 3,000 and 7,000, could have easily driven first dwarf hippos, and then dwarf elephants, to extinction. Our model showed the process would have taken less than 1,000 years. This prediction matches the sequence of extinction inferred from the palaeontological record.

Our results provide strong evidence that palaeolithic peoples in Cyprus were at least partially, if not entirely, responsible for megafauna extinctions during the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene.

Cyprus was the perfect place to test our models because the island offers an ideal set of conditions to examine whether the arrival of humans ultimately led to the extinction of its megafauna. This is because Cyprus was a relatively simple test case – a small island of around 11,000 square kilometres at the time, with only two species of megafauna.

Our research therefore improves our understanding of how even small human populations can disrupt ecosystems and cause major extinctions, particularly in times of rapid environmental change.

Read more: How the extinction of ice age mammals may have forced us to invent civilisation

Corey J. A. Bradshaw receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Christian Reepmeyer receives funding from the Australan Research Council and the German Foreign Office.

Theodora Moutsiou receives funding from the European Regional Development Fund and the Republic of Cyprus through the Research and Innovation Foundation (EXCELLENCE/0421/0050) for the project Modelling Demography and Adaptation in the Initial Peopling of the Eastern Mediterranean Islandscape (MIGRATE, 2022–2024).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.