Over the last few decades, planetary scientists have been steadily adding to the list of moons in our solar system that may harbor interior oceans either currently or at some point in their past. For the most part, these moons (such as Europa or Enceladus) have been gravitationally bound to the gas giants Jupiter or Saturn.

Recently, though, planetary scientists have been turning their attention further afield, towards the ice giant Uranus, the coldest planet in the solar system. And now, new research based on images taken by the Voyager 2 spacecraft has suggested that Miranda, a small Uranian icy moon, may have once possessed a deep liquid water ocean beneath its surface.

What's more, remnants of that ocean may still exist on Miranda today.

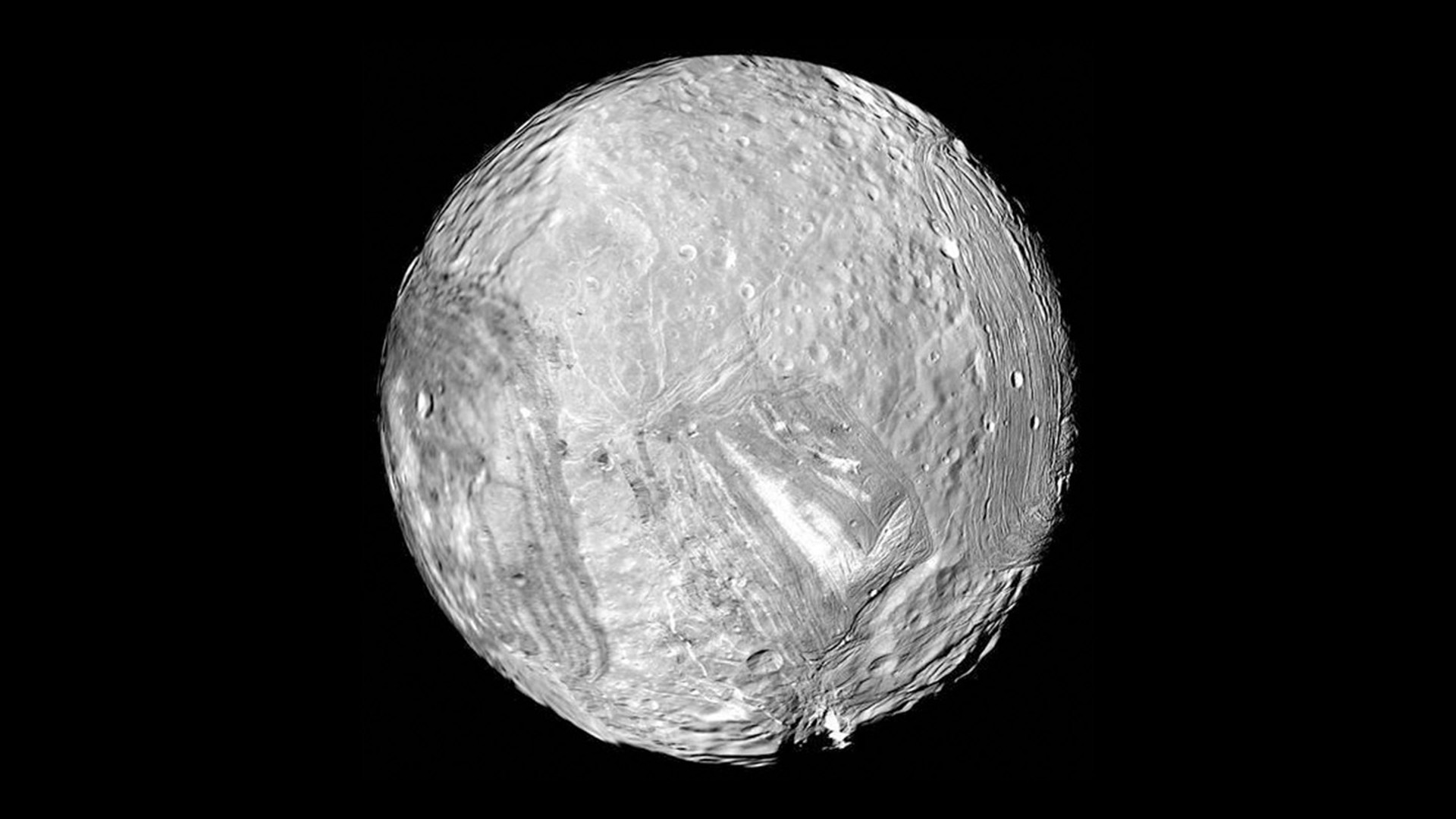

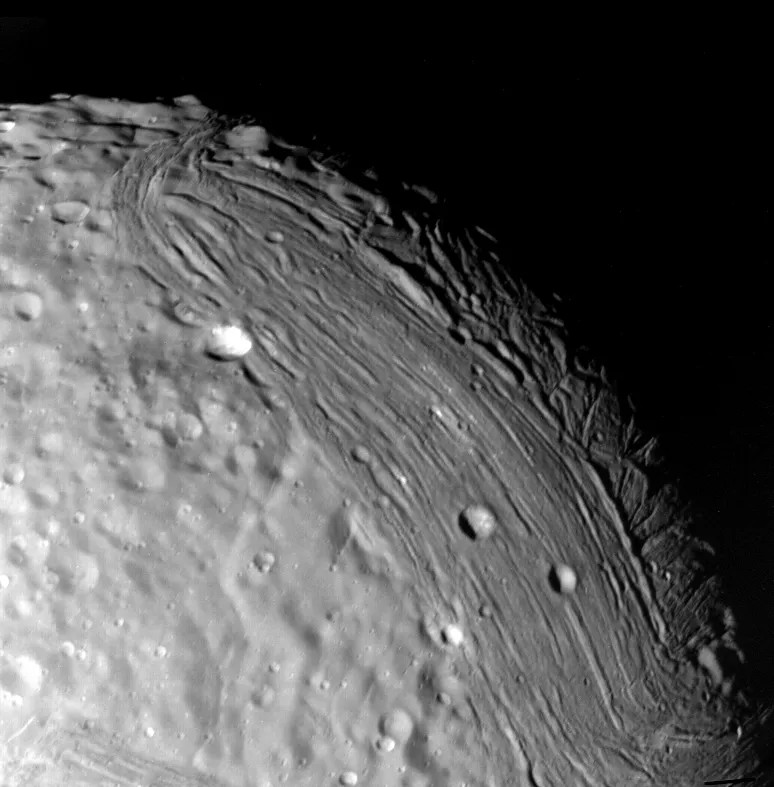

When the Voyager 2 spacecraft cruised past Miranda in 1986, it captured images of its southern hemisphere. The resulting pictures revealed a smattering of different geological features on its surface, including grooved terrain, rough scarps, and cratered areas.

Researchers, such as Tom Nordheim, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), wanted to explain Miranda's bizarre geology by reverse engineering the surface features, working out what type of internal structures could best explain how the moon came to look like it does today.

The team mapped the moon's various surface features, such as the cracks and ridges seen by Voyager 2, before developing a computer model to test an array of possible compositions of the moon's interior that could best explain the stress patterns seen on the moon's surface.

The computer model found that internal composition that produced the closest match between stress patterns on the surface and the moon's actual surface geology was the presence of a deep ocean beneath Miranda's surface that existed between 100-500 million years ago. According to their models, the ocean may have once measured 62 miles (100 kilometers) deep, buried beneath 19 miles (30 kilometers) of surface ice.

Miranda has a radius of just 146 miles (235 kilometers), which means the ocean would have taken up almost half the moon's entire body. It also means that finding such an ocean is unlikely. "To find evidence of an ocean inside a small object like Miranda is incredibly surprising," Nordheim said in a statement about the new research.

"It helps build on the story that some of these moons at Uranus may be really interesting — that there may be several ocean worlds around one of the most distant planets in our solar system, which is both exciting and bizarre," he continued.

Researchers speculate that the tidal focus between Miranda and other nearby moons were crucial to keeping Miranda's interior warm enough to sustain a liquid ocean. The gravitational stretching and compressing of Miranda, amplified by orbital resonances with other moons in its past, could have generated enough frictional energy to keep it warm enough from freezing over.

Similarly, Jupiter's moons Io and Europa have a 2:1 resonance (for every two orbits Io makes around Jupiter, Europa makes one), which generates enough tidal forces to sustain an ocean beneath Europa's surface.

Miranda eventually fell out of sync with one of the other Uranian moons, nullifying the mechanism keeping its interior warm. Researchers don't think Miranda has fully frozen over yet though, as it should have expanded, causing telltale crack on its surface.

"We won't know for sure that it even has an ocean until we go back and collect more data," Nordheim says.

"We're squeezing the last bit of science we can from Voyager 2's images. For now, we're excited by the possibilities and eager to return to study Uranus and its potential ocean moons in depth."

This new research was published in The Planetary Science Journal on Oct. 15.