There is a growing threat to the rule of law, democracy and human rights in Europe. It manifests as seemingly run-of-the-mill lawsuits. However, on closer inspection, many lawsuits are not as they seem.

Rather than attempting to remedy a wrong, lawsuits can have a much more insidious goal – to suppress truths and to silence criticism. These lawsuits are known as “strategic lawsuits against public participation” or Slapps.

Slapps target people who speak out on anything from climate change to money laundering. For those who would rather their critics stay silent, and their wrongdoings go unreported, there is a playbook of abusive litigation tactics readily available.

These tactics are enlisted by the rich and powerful to drive up the financial and psychological burden of defending a lawsuit until their opponents are left with no choice but to stop reporting or campaigning. They tend to wipe the public record clean, and to isolate the few who are able to resist attempts at censorship, sometimes with fatal consequences.

Such was the case for Daphne Caruana Galizia, the Maltese investigative journalist assassinated on October 16 2017. At the time of her murder, she had dozens of lawsuits pending against her for rigorous reporting on a web of corruption – a chilling reminder of the lengths some people will go to to shut down criticism.

We were recently commissioned to write a report for the EU Parliament analysing the use of such lawsuits across the EU since January 2022. What we found was unsettling.

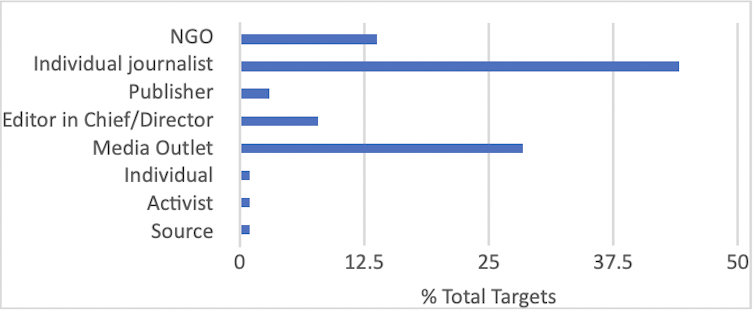

We identified 47 lawsuits targeting over 100 people, including journalists and campaigners. And these were the cases we were able to identify. It’s clear from the existence of anonymised data that these cases are just the tip of the iceberg.

These 47 cases concerned over 80 public interest matters, including journalistic reporting on corruption and financial crime. If the Slapps succeed, they could wipe the public record of important information that would influence everything from how we vote to what we consume. These lawsuits thereby have a chilling effect far beyond the immediate target.

Who gets Slapped?

There is a clear need for the EU to protect freedom of expression and the freedom of the press by empowering people like Caruana Galizia to ask courts to strike out these abusive lawsuits at an early stage. And this is precisely what the EU is doing. EU legislators are now negotiating the final text of an Anti-Slapp directive, colloquially termed “Daphne’s law”.

However, our report shows some of the small changes proposed to the language of Daphne’s law could leave most Slapp victims outside its protection.

Immediate stumbling block

For the EU to legislate on Slapps, it first had to establish that it had the power to do so. This was confirmed via article 81 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which allows the EU to legislate on matters with cross-border implications. So, for a Slapp to come within the scope of the proposed protections, it must first be classified as having “cross-border implications”. This is where the first problem arises.

There is disagreement between the EU institutions as to what amounts to a cross-border implication. The European Commission proposes that it means any civil lawsuit where at least one of the parties involved lives in a different EU member state to where the lawsuit is being heard or where the communication (for example, a newspaper article or blogpost) concerns a matter of public interest which is relevant to more than one member state or where the claimant has opened a legal action in more than one member state.

The Council of the European Union, which is made up of ministers from the member states’ governments, on the other hand, wants to remove any definition. This would produce uncertainty and could end up removing most cases from the scope of the directive.

There is a fear that without a clear definition in the directive, states would be free to adopt a narrow definition of “cross-border” as only capturing cases where the defendant lives in a different country to the court hearing the case.

Most cases are cross-border

We found that over 85% of cases concerned public interest matters which were relevant to more than one member state. One of the cases, for example, related to the procurement of medical supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Another targeted three journalists reporting on alleged corruption in Bulgaria, at its border with Turkey and Greece.

On the other hand, the domicile of the defendant and the court differed in only 4% of cases. This means that if the second part of the Commission’s understanding is left out of the final directive, or if, as the Council suggests, the definition of cross-border implications is removed entirely, we might see a situation where only a small percentage of Slapp victims are protected by the directive.

Read more: Slapps: the rise of lawsuits targeting investigative journalists

The other big issue is that the proposal sets too high a bar for dismissing a Slapp. The target has to prove that the Slapp is unfounded beyond any reasonable doubt. Any Slapp claimant with a competent lawyer can defeat such a challenge – and that certainly tends to be the case for the powerful actors who often bring Slapp claims.

The impact of this hurdle cannot be overstated. None of the cases we analysed could meet such a standard. Instead, the EU should protect people whenever these lawsuits show signs of being abusive.

Without freedom to genuinely report on matters of public interest, our democracies will slowly wither. As the Anti-Slapp directive makes its way through the final stages of the legislative process, now is a pivotal time to remember what is at stake.

Anti-Slapp laws do not only seek to protect the Slapp target – they are an attempt to ensure that information is a public resource and not one controlled by the rich and powerful.

Francesca Farrington has consulted to the European Parliament, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe (CASE).

Justin Borg-Barthet has consulted to the European Parliament, the European Commission, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe (CASE).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.