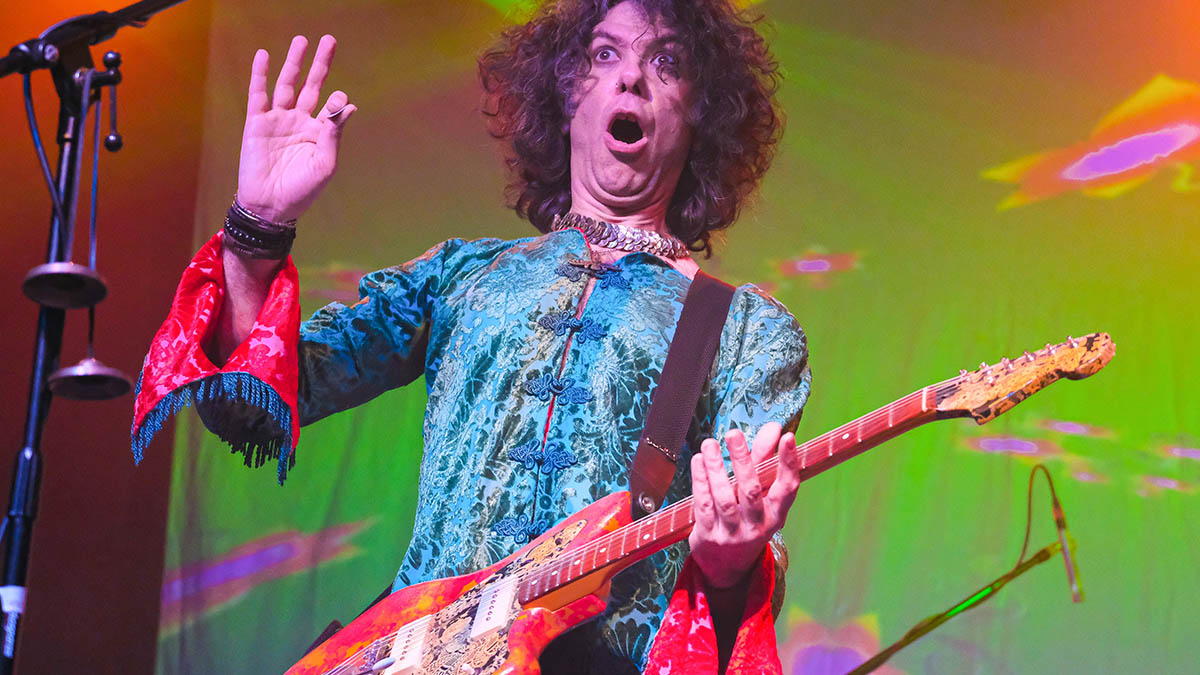

Psychedelic rock has never really gone away, but there’s a palpable sense it is having a bit of a resurgence – or at least a very vivid flashback – at the moment. And right at the centre of that growing musical mandala is Kavus Torabi.

A former member of seminal art-pop outfit Cardiacs, he’s been the frontman of Gong for the past eight years, broadening that band’s rich catalogue of lysergic prog with compelling new music.

Somewhat improbably, he’s also the musical partner-in-crime of snooker legend Steve Davis, who has found his new métier playing modular synth in an improvisational trio called The Utopia Strong with Kavus and traditional pipes specialist Mike York.

We venture out to Glastonbury – still a centre for esoterica of all stripes – to find out how Kavus makes his intrepid vision for guitar work all across this universe of sound.

Your musical partnership with Steve Davis has led to a band based on live improvisation combining guitar with modular synthesis. How did that come about?

“I met Steve at a show that [French prog outfit] Magma was doing. I knew he was a huge Magma fan – I’m a massive fan myself – and I’d seen him at Magma gigs in the UK but was a bit shy to talk to him because, you know, he’s Steve Davis. But I saw him in France and started talking to him because I thought we were probably the only Brits there. And so I started chatting, and, within about 30 seconds of talking to him, he stopped being Steve Davis the snooker player and we really, really got on well.

“I found out he was doing a radio show and he got me on as a guest for the show. He turned me on to so much amazing music and hopefully I turned him on to a lot of stuff. I mean, I’d kind of turned him on to a lot of electronic stuff that he didn’t know about – particularly things like Autechre and Aphex Twin – which is right up his street and which I think of as being kind of like prog music anyway: uber-dense, really complex, lots and lots of different meters. So then he said, ‘This radio show is really fun. Why don’t we start doing it together?’”

“We were doing the radio show together for a few years, every week, which was great, and that led to us getting asked to DJ at this electronic music festival down in Minehead called Bloc. We were playing the groovier end of our record collections.

“We weren’t really playing electronic music necessarily… we’d play Peaches En Regalia by Zappa, Supernaut by Black Sabbath, anything from our collection that seemed like you could dance to it. And that became our particular weird brand.

“We ended up getting asked to play Glastonbury, and then we got an agent and, for a few years, we were DJing. At the right festivals, it would go down really well. But at the wrong ones, the more mainstream ones, we’d empty the place!”

How did you start making music together as a band in The Utopia Strong?

“I’d always thought that Steve was incredibly musical. I mean, while we were doing the radio show, he’d be playing some insanely complex, avant-prog from Belgium or something, and he’d be playing and whistling along with these really abstruse melodies… And I said, ‘Steve, I know some incredible drummers that can’t get their heads round these polyrhythms and stuff.’

We had no intention of forming a group at that stage. I just had my guitar and an amp and my pedals and my harmonium, and Mike had his modular synth setup and Steve had his modular setup

“So I knew he was wired that way and I knew his taste was brilliant. Once he got into modular synthesis, the sounds he was getting were amazing… So we had this idea – let’s have a jam with me, Mike and Steve. We had no intention of forming a group at that stage.

“I just had my guitar and an amp and my pedals and my harmonium, and Mike had his modular synth setup and Steve had his modular setup. But Mike had brought along his laptop and said, ‘Well, let’s just record it anyway.’ And so we spent a day jamming and improvising.

“When we listened back to it that evening, we suddenly started going, ‘Actually, some of this is really good.’ The next day, we started honing it a bit. Even then we weren’t planning on being a band. But I was thinking, ‘Oh, this would sound really nice with a bit of acoustic guitar on it,’ and stuff like that.

“Over the course of the next few months, we went on to record some Rhodes piano, percussion and Mike on pipes. And so, between Steve’s place and here, we made what became the first album. We ended up spending about eight months on this record – really, really working on the overdubs and the arrangement. By the end of it, we knew these guys at Rocket Recordings, and we gave them the CD. They said, ‘Yeah, we love it, we’d like to put it out.’ Then we had to become a group.

“Three years on, we’ve really got into doing it and the way we’re making records is really growing as well. So I feel there’s very little limit to what we’re doing.”

Your other main gig is as frontman and guitarist of the current incarnation of Gong. The band was such a pioneering force in late-’60s psychedelic rock – how do you approach making music as Gong today?

“Joining Gong was really weird. What happened is Daevid Allen asked me to join the band. I said, ‘But you’ve never heard me play, Daevid.’ And he said, ‘Oh, I don’t need to – I want you to bring fire.’ The first jam we had was down in a rehearsal place in New Cross.

“The thing was, all the way from being 16, I’d write a lot of riffs and think, ‘Hmm, it’s a bit too Gong-y,’ and I’d put it to one side. I couldn’t use it because it sounded too inspired by Gong. So Daevid turned up at the rehearsal and I’d come up with a riff that day.

“I was there early – because I’m always early – and I was playing this riff and he started singing along to it. He said, ‘Oh, that’s great. Got any more of them?’ Fucking hundreds! I’d been storing all these riffs for the day that I got asked to join Gong [laughs]!”

What happened when Daevid Allen fell ill with cancer?

“When Daevid got ill, we’d just made a new record, ICU, and we had to go out and promote it. We’d got a 48-date tour booked. Once Daevid dropped out because he’d been diagnosed with cancer, most of those gigs got cancelled except for about eight or nine. I just thought, ‘This is a terrible idea.’

“But Daevid wanted us to continue and we had to promote the album. So I said, ‘Okay, we’ll do it. But after this, I’m out,’ and the rest of the band agreed. But then, as we started to rehearse this stuff, it was like, ‘Hang on… this might have something.’ So we brought in the drummer Cheb Nettles, who is the best drummer I’ve ever played with, and we realised it really did have something.”

“At the end of this mini-tour, people were saying, ‘Well, you are going to do more, aren’t you?’ And my attitude – and all of our attitudes – was, well, we’ve got to write stuff. If we write stuff and it’s good, then we’ll do it. Because it felt really bogus to me that we were this band with no original members. But then it struck me that even by 1975, there were no original members in Gong, really. And so Gong is not so much of a band than a mythology.

“We’re about to record another studio album after this tour with Ozric Tentacles. I won’t say it’s getting bigger and bigger, but it’s certainly not a nostalgia band. The last tour we did, we played a two-hour set and we only played one old Gong tune – Master Builder. The rest of it was all stuff we’ve written and not a single person came up and said, ‘I wish you’d done more of the old stuff.’ So Gong now is us carrying on.

“I think by now we’ve probably lost all the people who have said, ‘No Daevid, no Gong’ and that’s fine and totally understandable. But we’re doing our own thing. Meanwhile, I get to have the greatest job in the world on the wages of a cleaner, really [laughs]! There’s not much money in psychedelic music, but the reward is just to be creating music. And the band are such brilliant musicians. The other thing about Gong is it’s brought me back to lead guitar again, after years of not really playing it.”

What exactly inspired you to play more lead again?

“I had a real change during lockdown, and also Gong put me in a position where I came back to playing the guitar solos. My playing is so different as a lead player compared with what it was when I was a teenager doing the metal stuff. I mean, [these days] my big influence is this French hurdy-gurdy player called Valentin Clastrier, who just has this incredible melodic language. That’s really the kind of thing I’m trying to do with lead guitar in a way.

“What happened during lockdown is I got so miserable I went a bit nutty, actually: I couldn’t work on music and I got really depressed being stuck in my flat. It’s really hard when I feel like that – I’ve only had it three times in my life, a sort of depression… But this time I thought, ‘Okay, I know what this is – it’s depression, fine.’ And so I just decided, because I couldn’t write tunes, that I was going to start correcting all the sloppy habits I’ve had as a guitar player going back to being nine years old. And for the first time ever in my life, I started working on just scales.

“I’ve never, ever done that; guitar was always a means to writing songs. I’d been turned on to this New York jazz guy called Jimmy Bruno and he had this very simple exercise where he just shows you where the ‘white notes’ are [corresponding to those on the piano] on the guitar in all these different positions. That’s a good place to start.”

“I would spend five, six, seven, eight hours a day just playing scales. And I’ve never done that before. This is me at, like, 48 years old, just watching YouTube and playing one position really slowly for three hours. Each day, I’d go to bed and think, ‘Well, at least I’ve made myself a better guitar player today – at least the one thing I’ve done today is I’ve got better.’

“I started to realise lots of things: I hadn’t realised the disconnect between my left and right hand before, how they weren’t really talking to each other properly. And so I really started to unlock something, I started to really unlock the fretboard. This is someone who’s been playing guitar since they were eight or nine years old, finally unlocking the fretboard.

“After that, it became like an addiction that I had to play guitar, I had to do scales every day. So getting really good at guitar is my goal now. Because the great thing with any instrument is that it’s not like a computer game, there’s no end point. You can only ever get better, only ever go deeper in. I was amazed how much that unlocked this instrument that I’ve always had this sort of love affair with.”

You put in brilliant performances in the 2019 band that Steve Hillage put together to revisit his post-Gong 1970s and ’80s solo work. What did you learn, as a guitarist, from playing alongside Steve?

“What I noticed from doing that tour from 2019 is that Steve is very, very fastidious about rehearsing, which I am as well; I can never rehearse enough. I always wish there were two more days of rehearsal before we start. I’m really, really into it. And so I really liked that he is.

“He was already brilliant, but what I noticed about doing that tour is that every night he was getting better and better at the guitar. He was getting more and more deeply into it and all of the band were [agog]. It was really, really good. Because I think he’d sort of put guitar to one side to concentrate on the techno stuff, which is great. But hearing him get back to playing lead… it was lovely.

“We used to open each night with a track called Talking To The Sun, and at the very beginning it has this full-on twin-guitar harmony lead line. I’ve always loved a harmony lead and – this sounds really corny, but – just to be stood there with Steve, looking at each other, and doing the real Hotel California moment [laughs]. I was like, ‘Fucking hell! I’m playing guitar with Steve Hillage!”

- International Treasure is out now via Rocket Recordings.