Good morning, I’m Dan Gartland. I hope everyone had a restful holiday weekend.

In today’s SI:AM:

⚾ The Mariners’ rookie sensation

🇯🇵 The new life of a sumo superstar

If you're reading this on SI.com, you can sign up to get this free newsletter in your inbox each weekday at SI.com/newsletters.

He could be one of the youngest All-Stars ever

Mariners rookie Julio Rodríguez is showing why he was ranked as a consensus top-three prospect in baseball before this season.

With a home run yesterday, Rodríguez set a record for the fewest games played to reach 15 homers and 20 stolen bases. He did so in his 81st game, one game fewer than Ellis Burks in 1987 and nine games fewer than Barry Bonds in ’86. He’s also one of just five players (joining Ronald Acuña Jr, Mike Trout, Andruw Jones and Cesar Cedeno) with at least 15 homers and 20 steals in any 81-game stretch at 21 or younger.

And his home run yesterday wasn’t just any homer—he blasted one 429 feet (108.3 mph off the bat) on top of the Western Metal Supply Co. building in San Diego. That kind of power is a big part of what makes Rodríguez such an enticing prospect. The fact that he combines power with top-notch speed is even more impressive. He’s one of seven centerfielders in the majors with at least 15 home runs this season and leads the American League with 20 steals—and he’s doing it all at 21.

That combination of skills is why Rodríguez rocketed through the Mariners’ system after he was signed as a 16-year-old in 2017. He skipped right past rookie ball and Low A in ’19, making his American debut for Class A West Virginia. Even the canceled 2020 minor league season couldn’t slow him down. He dominated at Double A last season and then skipped right to the majors.

It’s not like there aren’t holes in Rodríguez’s game (he has struck out 91 times this season, third most in the AL) but he appears to be acclimating to the major leagues nicely. After a rough April in which he posted a dismal .260 slugging percentage, Rodríguez improved his OPS in May and June. His OPS last month was a stout .906 and it sits at .824 for the season, making him one of seven rookies who have played at least half of their teams games this season with an OPS of at least .800. When the All-Star reserves are announced later this month, Rodríguez definitely deserves a spot on the team.

The best of Sports Illustrated

In today’s Daily Cover, Alex Prewitt has the story of Ryuichi Yamamoto, a sumo wrestler who was forced to retire after a match-fixing scandal and is now trying to make it in Hollywood:

“You may not recognize the name, but chances are you have come across his work: On top of making hundreds of appearances in commercials, on news programs and in live demonstrations at events ranging from anime conventions to cultural festivals, Yama has danced alongside One Direction and overhead-pressed Ed Sheeran in music videos; helped form a harem for Owen Wilson’s character in Zoolander 2; and taught sumo to contestants on Season 11 of The Bachelorette. An argument can be made that no other rikishi of his caliber, past or present, has achieved this level of global reach.”

For yesterday’s Daily Cover, Ben Pickman spoke with the guy who created the “Ballsack Sports” Twitter account that became a runaway hit earlier this year. … Chris Mannix writes that a potential Kevin Durant trade would define Sean Marks’s tenure as GM of the Nets. … The big question mark during this latest round of college conference realignment, Pat Forde writes, is Notre Dame—but the Irish can afford to wait.

Around the sports world

White Sox closer Liam Hendriks spoke at length about gun control following last night’s game after the mass shooting in the Chicago suburb of Highland Park. … Brittney Griner wrote a letter to President Joe Biden asking him directly for help in her case. … A British court ruled in favor of Ian Poulter and two other LIV golfers, allowing them to play in the Scottish Open this week. … The Sharks are set to hire Mike Grier as the NHL’s first Black general manager. … Christian Eriksen has agreed to terms with Manchester United, one year after he went into cardiac arrest on the field at the European Championships.

The top five...

… plays in baseball yesterday:

5. This chaotic play in the Mariners-Padres game.

4. Yordan Álvarez’s long walk-off homer for the Astros.

3. Seiya Suzuki’s go-ahead inside-the-park home run for the Cubs.

2. Brewers catcher Victor Caratini’s walk-off three-run homer in the 10th after the Cubs blew the lead.

1. Byron Buxton and Gio Urshela turning the first 8–5 triple play in MLB history.

SIQ

On this day in 1898, Lizzie Arlington became the first woman to appear in an American professional game in which sport?

Friday’s SIQ: What did the so-called “Rozelle Rule,” which NFL players went on strike to protest in 1974, permit the commissioner to do?

Answer: Assign compensation to teams that lost free agents. At that time, teams signing free agents were required to provide compensation to the player’s former team in the form of draft picks or players. If the two teams could not agree on compensation, commissioner Pete Rozelle had the authority to simply declare which players and/or picks would be sent in return.

The NFLPA challenged the Rozelle Rule in May 1972 with a lawsuit filed by 32 players. In December ’75, a federal judge struck down the rule as a violation of antitrust laws. Though Rozelle had exercised the rule only five times, critics said that it restricted free movement of players (similar to the effect of the qualifying offer in baseball) by disincentivizing teams from signing free agents.

The Rozelle Rule wasn’t the only issue at play. Players also wanted things like the abolition of the draft and more lax curfew rules during training camp. The strike was short-lived, lasting just 42 days, and did not disrupt the regular season, although members of the union boycotted training camps when they opened that month. The annual Hall of Fame game became a battleground for the fight between players and owners, with some three dozen union members showing up in Canton to picket while a bunch of rookies and free agents (not members of the union) played in Bills and Cardinals uniforms.

The display was featured on the cover of the Aug. 5, 1974, issue of SI. The magazine sent three photographers to capture the scene and in 2014, on the 40th anniversary of the strike, their photos were reproduced online.

The issues facing the NFL were not unique. I wrote in last Tuesday’s newsletter about a similar issue in baseball from around the same time—Charlie Finley’s attempted sale of three players in 1976 and the handwringing about the effects of free agency on the less wealthy teams.

Here’s what Twins owner Calvin Griffith said about teams’ ability to “buy” players:

“I think it’s a terrible thing when two clubs go out there and start bidding to see who can buy a championship team. I think this shows that what the owners have been saying about the wealthy clubs getting the top players is true.”

And here’s what Rozelle said about free agency:

“If NFL players are given total freedom to negotiate their services, the league would be dominated by a few rich teams and would eventually lose both fan interest and revenue.”

Those quotes are identical in meaning—and identically incorrect. Management will always argue for the ability to maintain power and hold onto its money.

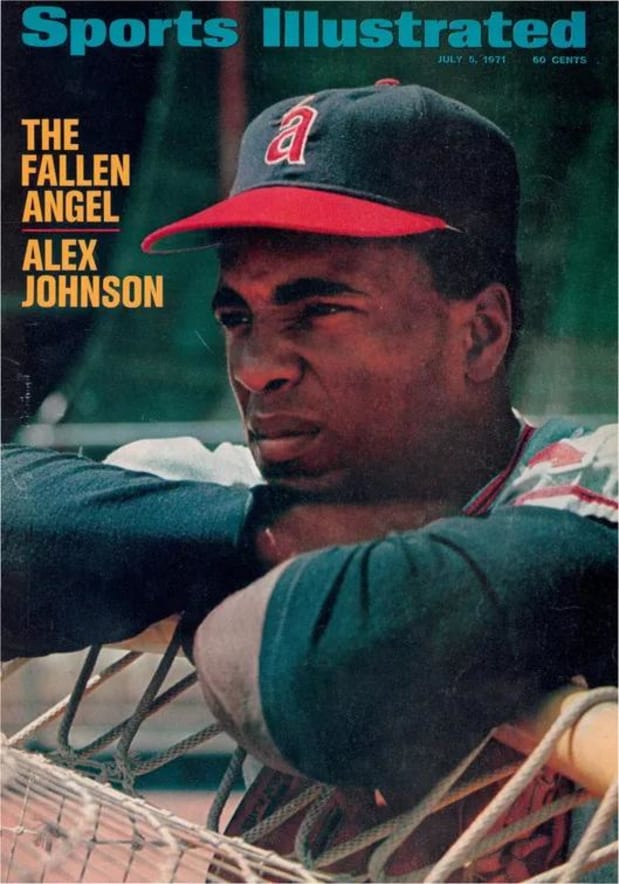

From the Vault: July 5, 1971

Fred Kaplan/Sports Illustrated

Throughout the first half of the 1971 season, Alex Johnson, the Angels’ best hitter a year earlier when he won the American League batting title, became their biggest headache. Teammates grew frustrated with Johnson’s lack of effort on the field, refusing to run out ground balls and making halfhearted defensive plays in the outfield. During a spring training game, Johnson even positioned himself defensively according to the shadow of a light tower. He was benched and fined repeatedly until, on June 25, the team suspended him indefinitely, without pay, “for failure to give his best efforts to the winning of games.”

Ron Fimrite’s article about Johnson’s confounding season lays out the grievances against him at great length. Everyone Fimrite spoke with said they liked Johnson well enough away from the ballpark but couldn’t understand why he was so sullen when he put his uniform on. His relationship with his good friend Chico Ruiz, his former teammate in Cincinnati and the godfather to his daughter, became so fractured that Ruiz pulled a gun on Johnson in the clubhouse during a game. (Both men had been used as pinch hitters and retired to the clubhouse to shower after their at-bats.)

What becomes clear when reading Fimrite’s story from a 21st century perspective is that Johnson must have been struggling with his mental health. And yet, only one person, outfielder Tony Conigliaro, suggested to Fimrite that Johnson might need help beyond a kick in the pants from his teammates:

“What do you see when you see a person walking down the street like this?” said Conigliaro, hunching his shoulders in a poor imitation of a Lon Chaney creation. “You know that person is sick, right? That’s how I feel about Alex. He’s got a problem deep inside him that he won’t talk about. He’s so hurt inside, it’s terrifying. He’s a great guy off the field. On the field, there’s something eating away at him.”

Marvin Miller, executive director of the MLB players association, agreed with Conigliaro. When Johnson was placed on the restricted list by commissioner Bowie Kuhn (after his suspension reached the maximum 30 days), Miller filed a grievance on Johnson’s behalf seeking to award him back pay. Two psychiatrists—one hired by the union and one hired by the league—found that Johnson was struggling emotionally. An arbitration board, citing the reports of the two psychiatrists, ruled in September 1971 that Johnson should be awarded nearly $30,000 in back pay because he should not have been punished by the team as a result of his mental health. Miller hailed the ruling as historic when it was issued.

“It means that a man who is emotionally disturbed is just as ill as one who has sustained an injury or has an ailment,” Miller said. “He should not be suspended or disciplined. He should be placed on the disabled list.”

Johnson denied in a 1990 interview with the Los Angeles Times that he had any emotional issues. When SI’s Jeff Pearlman caught up with Johnson for the magazine’s 1998 “Where Are They Now?” issue, he described the former outfielder as “bitter, caustic and slightly funny.”

Johnson ran a truck repair and leasing company after retiring from baseball.

“Do I enjoy my life?” he asked Pearlman rhetorically. “I enjoy not being on an airplane all the time. I enjoy not having to face everything I did. I just want to help people with their vehicles. It’s a nice, normal life—the thing I’ve always wanted.”

He died of cancer in 2015. He was 72.

Check out more of SI’s archives and historic images at vault.si.com.