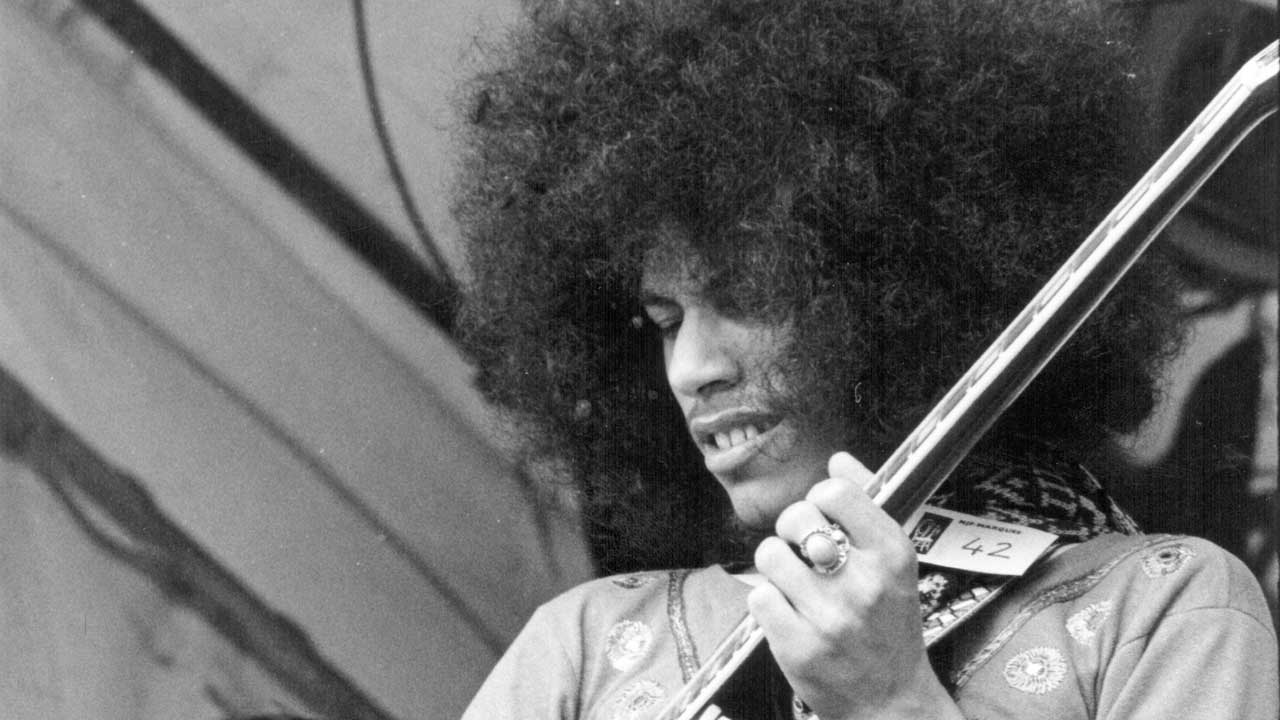

If ever there was a musician who went his own way, it’s Shuggie Otis. In 1974, he turned down an offer to replace Mick Taylor in The Rolling Stones. He played with Frank Zappa when he was 15, but said no to working with David Bowie, Spirit, Buddy Miles and Blood, Sweat And Tears. He told Quincy Jones he didn’t need a producer, he could do it all himself.

“I never had a problem with fame,” told The Blues magazine in 2016. “Put my face on a billboard, make me a star, I don’t mind that, but only if it’s for my music. I’m nobody’s sideman, I’m my own man. I’m Shuggie Otis.”

For decades, Shuggie Otis has enjoyed cult hero status; his 1974 third album, Inspiration Information, which he produced, arranged, sang and played guitar, bass, drums and keyboards on, is hailed a lost classic. A psychedelic soul and blues symphony, it paved the way for Prince and D’Angelo.

“It was supposed to take me overground,” he says, “but it was just too experimental. They expected me to record straight blues and they couldn’t open their minds to it. Soon after its release, I was dropped by the label. I didn’t think it was a big deal. I thought, I’ll have a new deal in a couple of weeks. Instead it’s taken 40 years to get signed again.”

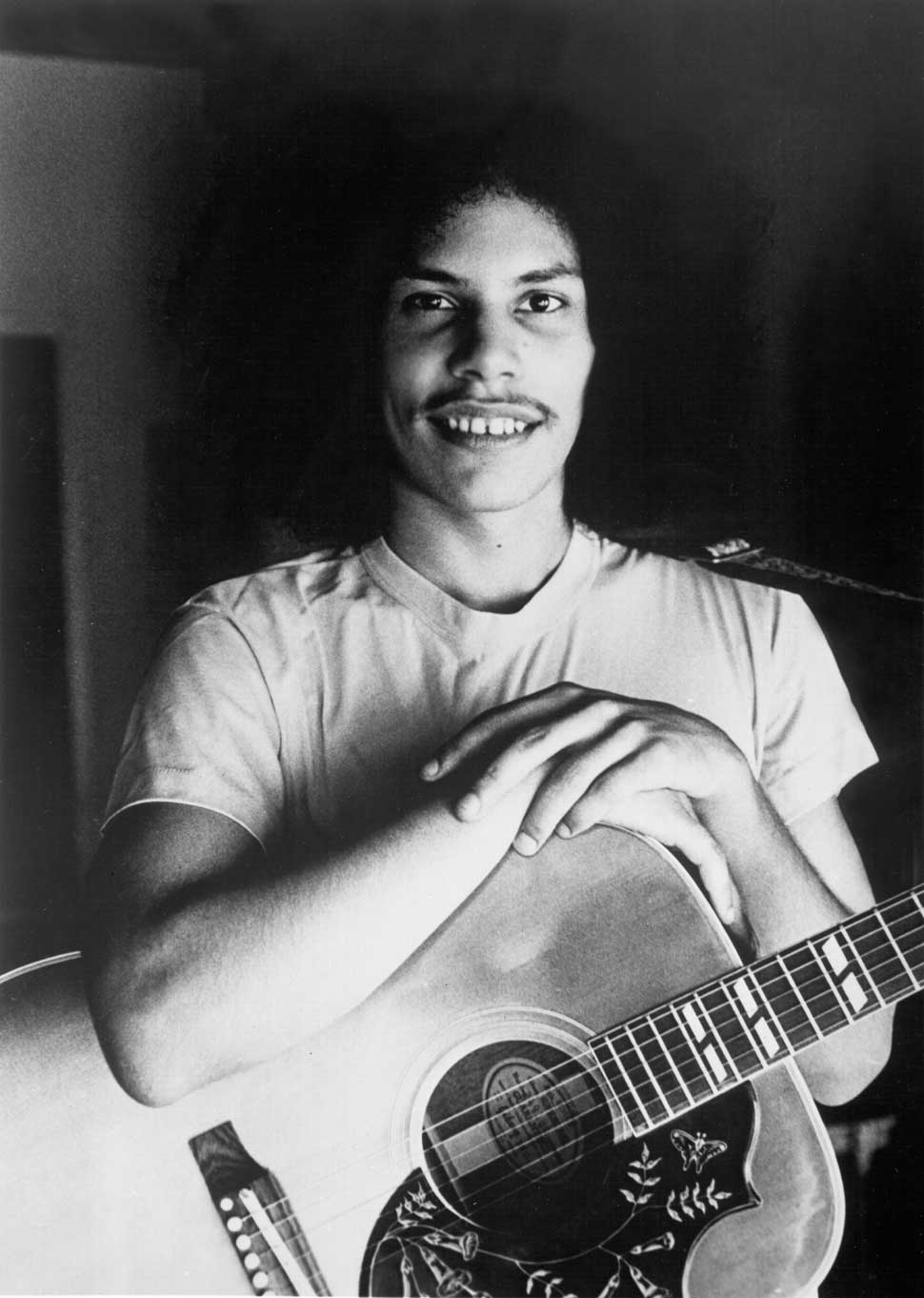

Born Johnny Alexander Veliotes, Otis, the son of bandleader, musician and R&B impresario Johnny Otis, honed his craft in his father’s band, making his recorded debut at the tender age of 12. At 15, he was discovered by Frank Zappa who helped him get a record deal with label owners the Bihari Brothers; the result, Johnny’s Cold Shot!, was his first proper billing on a record.

As a thank you, Otis played on Peaches en Regalia, the stand-out track on Zappa’s 1969 Hot Rats album. He also joined Al Kooper on the Kooper, Stills and Bloomfield Super Session album follow-up Kooper Session, before signing to CBS for three solo albums – 1970’s Here Comes Shuggie Otis, 1971’s Freedom Flight and 1974’s Inspiration Information.

It was a song he wrote and recorded for the second of those that broke through. Strawberry Letter 23, his paean to the summer of love, hit the US Billboard R&B No.1 spot and Hot 100 Top 5 when covered by the Brothers Johnson in 1977. The song is a fixture in Otis’ live show today, but, he says, the focus is on the future. It’s understandable: his wilderness years saw him succumb to alcohol abuse, although he is fully recovered now.

He’s in a good mood today, it’s early morning, the sun is shining and he is sat in his LA apartment surrounded by instruments; a selection of guitars, keyboards, drum machines and basses fill every available space. The Blues is here to talk to him about both his colourful past and what he’s doing now; there is a new single Ice Cream Party, a tremendous psych blues that meshes Johnny “Guitar” Watson with Hendrix. He’s also in the middle of recording his first studio album since Inspiration Information; its follow-up is in the pipeline too.

“People thought I had given up, I had gone into hiding. And there were hard times, but I’m no quitter. I kept making music, just no one was listening. Now I’m back and I’m pushing on.”

What are your first musical memories?

Watching my father’s band rehearse in our living room every Saturday and Sunday afternoon. It was such an exciting time. Rock’n’roll was in its infancy and there would be Don And Dewey, Johnny “Guitar” Watson and Jimmy Nolen in the living room.

Jimmy Nolen went on to play guitar in James Brown’s band…

Him and Johnny “Guitar” Watson were a huge influence on my own playing, T-Bone Walker too. But I didn’t think anything of them being round the house, they were just family friends.

You started out on the drums, not guitar though.

I used to go through my father’s scrapbook of his band on the road, there were lots of pictures of him playing the drums, so I naturally wanted to play the drums too. So my dad bought me a drum kit for Christmas when I was four years old. I was really serious about playing even though I was so young

What prompted the switch from playing drums to the guitar?

I was 11, I was playing little league baseball, I got bumped into and my left collarbone was broken. I was in a sling all summer and when we went back to school, The Beatles and the Stones and Jimi Hendrix were out and I got interested in guitar. I taught myself how to play out of a chord book. I had lessons for about a year but I wasn’t a good student. But every day when I got home from school, I’d get the guitar out of the closet and play. I practised all the time. I thought I was going to have huge fame, it was expected of me, everyone around me thought it.

Was it just the British Invasion that interested you at that time?

Because my father was a DJ and had his own radio and TV show, he got sent a lot of records, he had a huge collection, and I got to discover blues, R&B, soul, rock, even classical and I liked them all equally. Whatever felt good to me, I liked.

You debuted on record at 12. What do you remember of those first sessions?

My father had a studio in the garage. I was watching him record in it since I was six, so studios weren’t a strange environment for me. One day my father invited me to play guitar on a single he was recording, I Had A Sweet Dream, sung by Lillie Fort of The Raelettes, and then he asked me to play on Gene Connors’ cover of Ode To Billy Joe. I was just starting out so it was a big break.

Frank Zappa also gave you a helping hand as well.

Frank Zappa was doing a big interview for Life magazine and he was doing it on the 60s counterculture and the hippies – people thought he was a hippie but he was most definitely not a hippie. He was a big Johnny Otis fan as a teenager though, and he wanted to interview Dad.

So I went with Dad to his house while he was interviewed and then we went downstairs to jam in Frank’s basement after the interview. He kept all his instruments down there and he played guitar, I played guitar, my dad played this little organ, and that’s where he found out that I could play guitar. He called up the Bihari brothers who ran Modern, Kent and RPM records. He told them they needed to record a blues album with my dad and that I played guitar and should be involved too. My dad had worked with them before so they already knew who he was and what he was capable of.

That led to the 1968 Cold Shot! album credited to The Johnny Otis Show Featuring Mighty Mouth Evans And Shuggie Otis on Kent Records.

It didn’t hit nationally, but it really took off locally. The single Country Girl, it was really big in Los Angeles and people were saying positive things about me and I was really proud. I thought that I’d made it.

In a way you had, because then came 1970’s Kooper Session – Al Kooper Introduces Shuggie Otis.

I met Al Kooper at the Columbia Records music convention in Century City in Los Angeles. My dad and I had signed to Columbia on the back of the success of Cold Shot!. Al was standing not far away from me, he was with his wife. He walked over, introduced himself and said, “How would you like to do Super Session part two?” I said, “Of course.” He told me that Mike [Bloomfield] would be there. He’d already made the [1968] album Super Session with Mike and Stephen Stills.

Anyway, at some point Mike dropped out, I don’t know why, but it still turned out great. It was the first time I went on an airplane, flying to New York for Columbia Records. I was just 15 and Dad was really proud of me. We got the whole thing down in two nights after hours. Al was really instrumental in my early career. My dad number one, Frank Zappa number two, Al Kooper number three, Columbia Records number four.

The blues-rooted Here Comes Shuggie Otis from 1970 was your first album as a soloist.

Not really, although it is billed as that, but I still saw myself very much as a side person. I needed help with writing songs, I hadn’t written any really at that point and so my dad did a lot of the writing on the album. I did write the music to Oxford Gray, although my father had a lot to do with the orchestral arrangement on the song. The bit when the orchestra comes in with the slide guitar, that was my dad’s idea.

He even came up with the album title and the title of its follow-up, [1971’s] Freedom Flight, and he mixed Freedom Flight. But it was the perfect title, it summed up how I felt and the mood of the times. It was the early 70s, the black panthers, the hippies, revolution was still in the air.

Your father was pivotal in the evolution of rock’n’roll and R&B, not only as a bandleader, musician and composer, but as a facilitator and producer for such greats as Etta James, Big Mama Thornton, Little Willie John and Jackie Wilson. What was he like to work with in the studio?

As a producer my dad was always on top of it. He did not waste any time in the studio, he was a very businesslike person. If someone was singing out of tune, he’d stop the tape right there, he’d be like, “Let’s do it again.” He was never mean, or nasty or rude, just very to the point. He was all for doing the one-take session. If you could get it done in the first take, he was happy. That was his mindset, and he would always get the rhythm section down in the first take. That’s how they did it when he was first recording with a big jazz band, it was “come in, play it once, get out of here”. That’s how I do it now – rehearse, go into studio, do it.

On 1974’s third album, Inspiration Information, you really came of age.

It’s the first time I worked without my father, although he was there at the beginning of the sessions, which were at Columbia Studios in Hollywood. We had a month-long tour in the UK and Spain, and while we were in London we went to a convention. Dad told Columbia Records there that rather than give us an album advance, could they build a 16-track studio at the back of our house. So when that was finished, my dad said, “Go for it.” So I did. Sometimes I’d have someone run the machines, but most of the time it was just me in there.

You turned down an offer to replace Mick Taylor in The Rolling Stones while you were making Inspiration Information. Weren’t you tempted?

No, I really wasn’t.

How did the offer come about?

Billy Preston called me up one afternoon, my dad answered the phone, passed it over to me. Billy was a mutual friend of me and the Stones and he said, “I’m here with The Rolling Stones in Amsterdam and they’re looking for a guitar player. Do you want to join the group?” I said, “Billy, I’ve got my own group now and I’m playing tonight and tomorrow, I can’t.” He sounded a bit let down but seemed to understand.

You see I was so into my own music, I didn’t just want to be on stage and make money, I knew straight away when he asked me that I didn’t want to do it, I just wanted to work on my own thing. It was the same with Spirit, Blood Sweat & Tears and Bowie when they asked me. I would have said no to anyone at that time who asked me to join their band, I wanted to experiment with writing and arranging.

Buddy Miles wanted to record with you as well, didn’t he?

Yes, he and Billy Preston wanted to put a trio together with me. I did do a session with Buddy though, but it was with Al Kooper and Mike Bloomfield. We were recording in the Record Plant in Sausalito [California] and we were the first or one of the first bands to record there. We were supposed to be recording an album of instrumentals, and I ended up playing bass as Al got rid of the bassist on the second day.

I remember us doing Booker T And The MGs’ Hip Hug-Her, but after the third day I lost interest, and I said, “I wanna go home.” Mike said that was okay. He was a nice guy, he understood. Al Kooper was the boss of the session though, and not too happy, but it was four people going in four different directions, and it wasn’t working for me.

Outside of blues circles, you’re best known for writing Strawberry Letter 23.

I wrote the music on upright piano at home. My father had his own home studio, an eight-track in the garage downstairs. There was a little yellow upright piano in there, which I used to play on all the time, and I came up with the idea on that, then I came up with the harmony guitar part on the piano too. Writing the lyrics took me several hours, everyone said I must have been on LSD when I wrote them, but I was straight, I hadn’t tried anything at that point. But I was trying to relate to the hippie crowd, I perceived it as a love-in song, about being in a paradise.

What did you think when the Brothers Johnson had a hit with their version produced by Quincy Jones in 1977?

It was a great feeling. I thought people saw the song as a teenybopper song, that they thought it was silly, but here suddenly was validation and also money. It brought me my first money and that hit kept me going through the hard times. It kept me alive.

After the Brothers Johnson hit, Quincy Jones then asked to produce you, but you turned his offer down. Why?

Strawberry Letter 23 had just been a hit and the proposition sounded interesting at first. I gave him a tape of 10 songs. He didn’t go for them, but he still wanted to produce me, but he wanted to have control of the music and I did not like that at all. I’d done Inspiration Information on my own, that was how I wanted to work from now on. He was also going to pull out all the stops and try and make me a star, and that was scary too as it wouldn’t be on my own terms with my own music, it would be with Quincy Jones calling the shots.

But I called him up, when he was producing Chaka Khan. I asked him if I could hang out in the studio, he said, “Well there won’t be much time for hanging out.” I just wanted to check it out, see what was going on. Deep down I knew it wasn’t going to work.

You’d been dropped by your label by this time though, hadn’t you?

I had started on my fourth album and that’s when I got the news. I had sent them a couple of tracks, I was moving swiftly and then it was, “That’s it for you.” My dad came in and said I’d been dropped, he looked upset. It didn’t even depress me, I just thought there will be a new deal soon. So I kept recording, and I sent tapes to record companies every year, I was hopeful, but after a while I knew I was going to be rejected. There was interest but they always wanted me to have a producer, to give up artistic control and I wasn’t prepared to do that.

What is on the cards for the future?

Cleopatra Records got in touch, they asked if I wanted to record a new album, and I’m half way through it now. I’m playing all the instruments on it so far, the guitar, bass, drums and keyboard parts. The next stage is getting in Cedric Norah and Jimmetta Rose Smith – my guest vocalists – and then getting in some horns.

I’ve also started planning the album after that which will feature my live band, a quintet featuring my brother Nick Otis on drums and my son Eric Otis on guitar, then Swang on keyboards and backing vocals – he’s the vocalist in New York dance band Eastside Mix – and then Albert Wing on saxophone. He’s pretty well known.

Albert Wing as in the horn player for Johnny “Guitar” Watson.

That’s right, he sure can play, I’m very positive about this band.

And finally, where is your head at right now?

Well I survived, I’m still here, I still love music. There were depressing times, but there were good times too and there are good times to come. I’m not 16, just starting out now, I’m 62, but it’s not that different a place I’m in. I’m still practising all the time and it’s still exciting. It’s like a new inspiration has come over me. ✰

This interview originally appeared in The Blues Magazine in 2016. Shuggie Otis's fourth album, Inter-Fusion, was released by Cleopatra in 2018.