There is something different about the presidential aspirations of South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott. Several things, in fact.

Should Scott decide to make his candidacy official, those differences could alter the trajectory of the 2024 race.

Beyond that, they might even bend the arc of history.

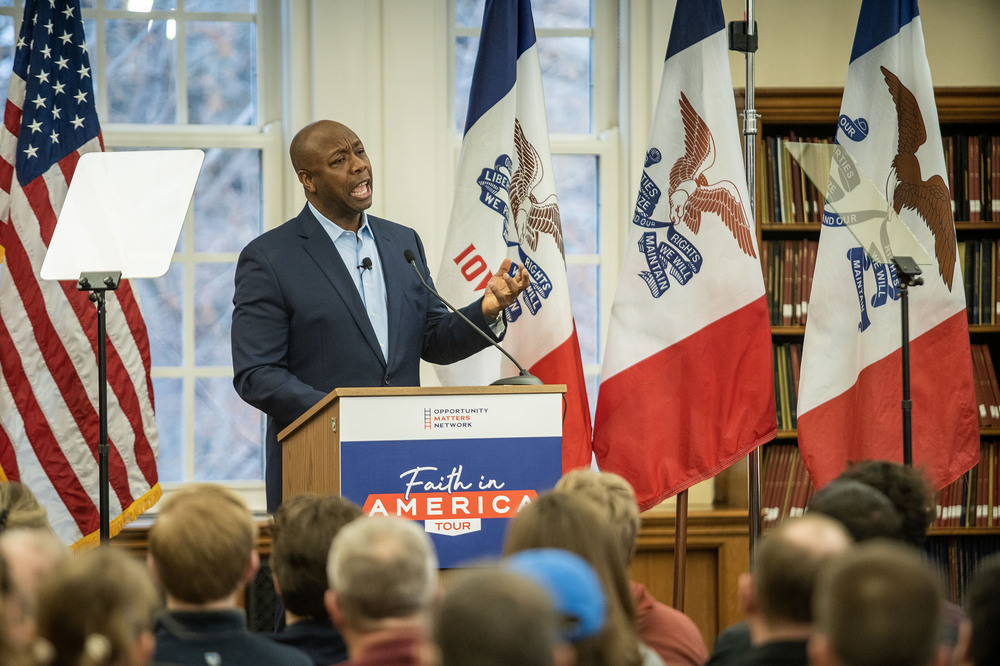

While there's absolutely nothing groundbreaking about a senator wanting to move his office 16 blocks down Pennsylvania Avenue — the lure of the White House has had enticed senators since the early 1800s, and equally so regardless of party — Scott is not just another ambitious senator from one of the major parties who goes on a national "listening tour" or visits Iowa around Presidents' Day, checking out the site of the caucuses that will commence the GOP's nominating process next year.

Scott is also Black, and that makes him anything but typical in the Senate. Indeed, he is one of just three Black senators today (four if you count Vice President Kamala Harris, who is the ceremonial president of the Senate and votes to break ties).

Even among this select group, Scott stands out because he is its only Republican. In fact, he is only the second Black Republican the voters of any state have sent to Washington in all of American history.

Take a moment to let that sink in.

A minority within a minority

The first Black Republican senator was Edward W. Brooke III of Massachusetts, elected to serve two terms from 1967 to 1979. In the 1870s, two Black men who were Republicans, Hiram Revels and Blanche K. Bruce, represented Mississippi in the Senate during the Reconstruction period that followed the Civil War. But like all senators in that era, they were not chosen at the ballot box. They were appointed by the governor or elected by their state legislature. And in Mississippi in those years, the legislature was watched over by federal troops.

After those troops left, segregationists and Jim Crow laws soon brought an end to the first era of African Americans in the Senate. It was not until Brooke in the 1960s that the Senate's color line was crossed again. And it was a dozen years after Brooke retired before the Senate welcomed Carol Moseley Braun of Illinois, the first Black woman senator and also the first to be a Democrat. A dozen years later that Illinois seat would be Barack Obama's.

Since then, six more African Americans have served in the Senate — all Democrats except Scott. The most recent is Raphael Warnock of Georgia, who defeated an incumbent Republican in 2021 and was reelected to a full term this last November. Warnock and Scott are the only African Americans from the Deep South to have ever won a popular election to the Senate.

Scott on the 2024 landscape

The 2024 Republican primaries are shaping up as a contest between former President Donald Trump and a flock of lesser figures who hope the frontrunner stumbles or fades. There is also the prospect of being the running mate — either for Trump or for someone else.

In fact, many see Scott as one in a growing field of contestants for vice president. And he plays the part, straddling the fence much as the others do, speaking of the party's "need for new leaders" but covering his bets by not attacking Trump directly.

In this he is like his onetime benefactor, Nikki Haley, who as governor of South Carolina in 2013 lifted Scott from his House seat with a senatorial appointment. (He subsequently won election to the seat in 2016 and 2022.)

Haley herself is a declared candidate for president, talking about a new generation taking over but not criticizing the former president, who appointed her U.S. ambassador to the United Nations.

It sounds dismissive to say someone is "running for VP," but we should remember that six of the 14 vice presidents elected before Harris have become president — including President Biden and Presidents George H.W. Bush, Gerald Ford, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon and Harry Truman. Several other vice presidents at least got the next party nomination for president, including Al Gore, who won the popular vote in 2000.

In short, there is no better route to the Oval Office than through the Office of the Vice President.

It should also be noted that running for president and dropping out early has been an excellent way to get on the national ticket, albeit in the second slot.

It should also be noted that making a show of presidential ambition early but then backing off has been an excellent way to get on the national ticket, albeit in the running mate role. Variants on that pattern have worked for every Democratic nominee for vice president from Harris in 2020 back to Lloyd Bentsen in 1988.

All of these vice presidential nominees were seen as providing balance and extra appeal to a ticket. Scott is well positioned to do the same especially if he gains national stature in the coming months but does not become one of the last two or three contenders for the top job.

At the same time, he could also become popular enough to add real energy to the 2024 ticket, much as Sarah Palin did for John McCain in 2008 or Geraldine Ferraro did for Mondale in 1984. Palin and Ferraro were the first women nominated for vice president in Republican and Democratic parties, respectively.

The "running for vice president" line is often meant as dismissive, and it has been used to marginalize both women and candidates of color over many cycles.

But if Scott were on the ticket in 2024, and if that ticket won, he might well be credited with changing the nature of partisan politics in our time.

Indeed, the very presence of a person of color among the prominent candidates might well change the conversation in 2024. Just by being in the debates and traveling the country Scott can alter the image of his party, an image that has taken hold since Nixon's "Southern Strategy" courted white votes in the Deep South for the GOP in the 1960s and Ronald Reagan did the same in the 1980s. Trump contributed his share to this image with his response to racial violence in Charlottesville, Va., in 2017 and to protests following the police killing of George Floyd in 2020.

The nature of Scott's appeal to swing voters and to people of color is largely personal, based in his life story of childhood poverty and a long climb to distinction. He has become quite adept at blending that story with the core beliefs of his party: self-reliance, distaste for government and reverence for religion and traditional social mores.

"Growing up in a single parent household, mired in poverty, the challenges that I faced from self-esteem to low grades were monumental," says Scott. "I overcame those challenges with grit, hard work and inspiration."

While the inspirational side of Scott's persona appeals to some Republican activists, he also takes pains to villainize the opposition. In the spirit of the contemporary discourse that is driven by social media, Scott is given to partisan hyperbole. In a recent appearance on Fox News, he said "the left today seems to be working on a blueprint on how to ruin America."

Contradictions that could make a kind of sense

Acerbic accusation is the argot of activists in both parties in the 2020s, and Scott would probably be hopelessly out of synch if he did not use it. But his persona in the Senate, and in his home state, has been far less partisan than potential rivals now competing for Trump's base voters. Scott has been a loyal member of his party, but one with whom Democratic colleagues can have a dialogue, or even cosponsor a bill.

In a recent appearance on Fox News, Scott was confronted by a host Shannon Bream, who noted the contradiction between that line and Scott's image of cordial collegiality in the Senate. Scott said it was necessary to highlight "the state of America and the weakness of the progressive movement" in order to offer "positive, optimistic solutions."

But this much is clear. Were Scott to be half of the GOP ticket next year, he would greatly complicate the Democrats' usual strategy. In close elections, Democrats have long depended on urban communities of color, especially African Americans, to provide the margin of victory in swing states such as Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin. That would be a steeper climb if Republicans put a Black man on the ticket.

Scott, with his well-honed speeches on self-reliance and enterprising spirit, may well be the best spokesman his party could have in reaching new citizens and communities of color where faith in the Democratic Party may already be waning.

This past week saw a white man finish first in a multicandidate primary for mayor of Chicago. The immediate consensus held that crime was the salient issue, and that support for police had become a winning message in urban, working class America. Could anyone carry that message better than a candidate whose mere presence onstage rebuts Democrats' assertions that the GOP is racist?

Little in common with previous Black candidates for president

There have been Black contenders for the Republican nomination before, beginning with the legendary Frederick Douglass in 1888. (He had first run in the Liberty Party in 1848, before the GOP existed.) But Douglass and others were primarily "message candidates" rather than actual contenders.

Prior to the first primaries in 2012, the nation got an earful of Herman Cain, a pizza chain executive who used commercial marketing slogans in his campaign. In 2016, brain surgeon Ben Carson made a deeper run into the primaries, earning nine convention delegates and lasting into March. Carson's performances in the 2015 debates were strong enough that he briefly led in GOP polls that fall.

Earlier, Alan Keyes, an African American author with a mesmerizing oratorical talent, sought the GOP nod in 1996, 2000 and 2008, collecting a handful of delegates. In 2008 he moved to the Constitution Party.

There are more antecedents for an African American candidate in the Democratic Party. That ground was broken by Channing Phillips, who received 67.5 votes at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. Shirley Chisholm got 152 votes at the 1972 Democratic Convention and Barbara Jordan ran in 1976, giving a memorable speech at the convention that nominated Jimmy Carter.

Scott might also look to the campaigns waged in the other party by another South Carolina native, Jesse Jackson. An ordained minister, Jackson had long since left the state and become prominent in the civil rights movement. Jackson had spent years striving to claim the mantle of his mentor, the Rev. Martin Luther King.

In 1984, Jackson declared himself a candidate for president in a large field of Democrats and gained attention with big rallies in cities and college towns. He garnered 466 votes at the convention that nominated Mondale and seemed a potential running mate before Mondale chose Ferraro.

Four years later, Jackson was back with an even more impressive campaign that won the Michigan caucuses. Jackson received 1,218.5 votes at the party convention, where he and his supporters were permitted to take over the proceedings for one night. Jackson was again seen as a strong prospect for running mate, but negotiations toward such a ticket did not bear fruit.

Scott does not have Jackson's talents as an orator or a magnet for media coverage. But his different strengths, and his differences from other prospective candidates, give him a chance to matter in the new politics of the 2020s.

They give him a chance to make a difference.