While the outcomes of the presidential nomination races are sure to gain the lion’s share of the attention in 2024, the spring is certain to include some interesting intra-party challenges. Some of the features of modern politics have become the battles over ideological purity, loyalty to party agenda, the sin of not supporting party leaders and disappointment on the part of voters that progress on issues has been slow.

This was not always the case. There was an era when elected leaders pursued agendas that were not explicitly approved by their party, when it was considered acceptable to create bipartisan legislation, when officials worked without fear of being ‘primaried’ for not supporting what other members of their party believed and when party members could challenge an incumbent without it being part of a larger war — often for the direction and soul of the party.

That all changed 45 years ago in the 1978 Republican Party primaries: It was at that moment when a sea change began and the concept of independence and bipartisanship, once a common trait, began to wane.

In the late 1970s, some Republican leaders first committed to remaking their party. While many factions within the party once existed — Eastern Establishment liberals, Midwestern moderates and conservatives from the south and west — many believed that the best course for the future was as a party for conservatives. Buoyed by Ronald Reagan’s challenge to Gerald Ford in 1976, the more sophisticated use of direct mail, and frustration with the lack of a party identity, the 1978 primaries were chosen to be their testing ground. Step one for this emboldened group was a purge of the infidels.

A targeted moderate

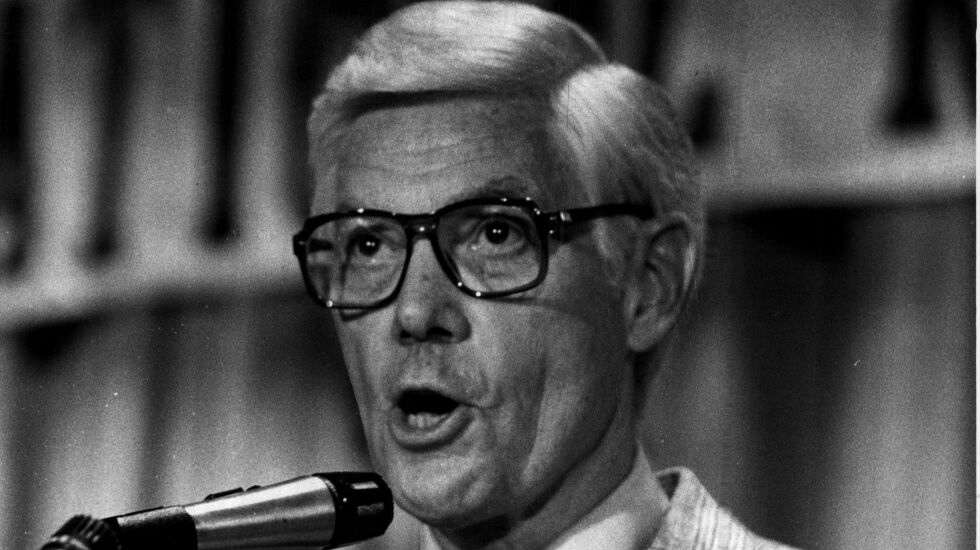

Three moderate Republicans found their way to the top of the conservatives’ hit list — two veteran northeastern senators (Clifford Case and Edward Brooke) and one House member, John Anderson of Rockford. Since Illinois was hosting the first primary in 1978, Anderson became the initial target. Anderson held the House Republican Conference chairmanship, so knocking off a party leader in the season’s opening electoral event would garner widespread attention.

Anderson was a good choice for a target by conservatives. He often strayed from the GOP agenda, had taken controversial positions that had lost him support in his district, and had little campaign experience.

His opponent was Don Lyon, a television evangelist who had conservative beliefs and values and media experience. This was not symbolic opposition — even though Lyon was a political novice, he dedicated himself to the campaign and ran to win.

Anderson tried to ignore the challenge, but that failed quickly. Lyon raised funds through direct mail, went to candidate training workshops, hired an experienced campaign manager and received support from conservatives around the country.

Lyon built his campaign around some of the same issues that still divide voters today — lower taxes, abortion, registration of handguns, foreign aid and government spending policies, as well as some issues of the era, like the ERA and the Panama Canal Treaty. The polls showed Lyon rising rapidly.

Anderson was an impressive congressman. He had an encyclopedic knowledge of legislation. He was a favorite of the news media, so he frequently appeared on national television. To bolster his GOP credentials, Anderson persuaded prominent Republicans to campaign for him. There were appearances by Ford, Henry Kissinger and Jack Kemp. Anderson raised a great deal of money, hired a political consulting firm, and aired television commercials — all things he had never done before. In March 1978, helped by a huge turnout, Anderson defeated Lyon 58% to 42%.

Wounds that remain today

Case and Brooke were less fortunate; emboldened by nearly knocking off Anderson, conservatives came out in force against them. Case lost his primary in June. Brooke narrowly survived his challenge in September but limped to a double-digit defeat in November. Rather than face another challenge, this would be Anderson’s final term.

Anderson won his race, but conservatives won the war for the soul and direction of the party. It became unacceptable to stray from party orthodoxy. Working with Democrats on legislation was frowned upon. Disloyalty to the party became an open wound. Those who questioned party ethos often found their way onto challengers’ hit lists. Democrats soon developed their own tests for purity.

Now, 45 years later, we still suffer from these wounds because the parties are unwilling to work together and civility is gone. When politicians from either aisle, be it Liz Cheney, Joe Manchin or Mike Pence, choose to speak out on their own, they do so at risk to their careers. So we ask — why did it become so important to conform and so wrong to work together for the common good?

Jim Mason is the author of “No Holding Back: The 1980 John B. Anderson Presidential Campaign.” He lives in New York City.

Send letters to letters@suntimes.com

The views and opinions expressed by contributors are their own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Chicago Sun-Times or any of its affiliates.