The mass 1944 breakout of Allied prisoners of war from the notorious Stalag Luft III camp was famously immortalised by Hollywood.

But for nearly 80 years the true stories of "The Great Escape" captives have remained hidden in sealed UK defence ministry files.

Now details of the experiences of these and other World War II detainees are being revealed for the first time after a treasure trove of wartime records was handed over.

On the night of March 23-24, 1944, more than 70 Allied airmen tunnelled out of the notorious PoW camp in Nazi-occupied Poland.

The escape was the culmination of months of work by the PoWs who used ingenious techniques not just to stage the breakout but also to receive and send information out of the camp.

The 1963 celluloid portrayal famously sees Steve McQueen's character trying -- and failing -- to jump his way to freedom on a stolen Nazi motorbike over barbed wire.

In real life, 73 of the 76 escapees were recaptured, according to Will Butler, joint curator of a new exhibition at the UK's National Archives.

"Fifty of those later captured were executed by the Gestapo," he told AFP.

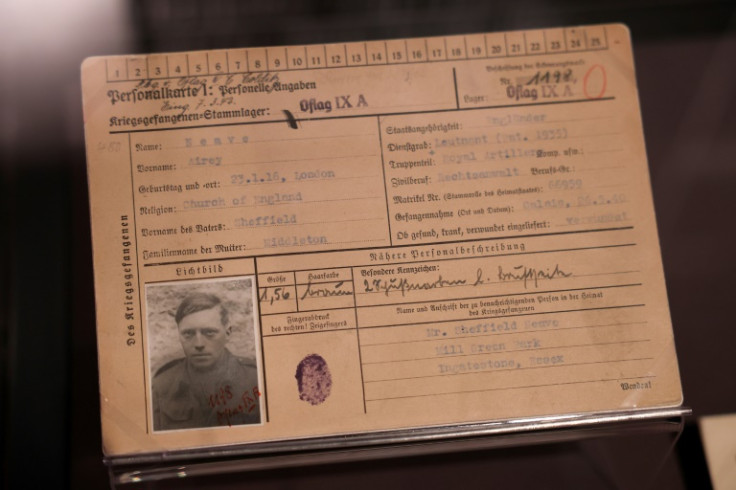

The exhibition, "Great Escapes: Remarkable Second World War Captives" which opens on Friday, explores some of the wartime techniques used by detainees to smuggle information.

One of the most popular methods was coded letters or letters with concealed information sent in apparently routine communications to with family members.

A clue in the form of something written in the letter that would only appear strange to the recipient would indicate that the letter should be passed on to military intelligence.

In one such letter, captured Spitfire pilot Peter Gardner concealed vital information inside a photo of fellow PoW Guy Griffiths.

Experts believe the mention of Griffiths in the letter to his mother could have been a concocted story and intended instead for British intelligence service MI9.

MI9 was set up the British government at the start of the war to assist escapes.

Gardner, captured after he bailed out over France in July 1941, hid his secret message by writing in tiny script -- unreadable without magnification -- painstakingly sandwiched between the image and its backing card.

The covert messages were often requests for items to be smuggled in to assist the escapers such as radio parts or in this case for forging fake documents.

"Had marked success with various documents supplied to number of escapees on 5 March, but have considerable difficulty obtaining originals to copy," he wrote.

"Therefore request tracing of identity card for foreign worker in Germany... Suggest suitable paper as fly leaves in books. Request also powdered Indian ink, three very fine nibs," he added in the 1942 secret letter.

Two years later forged documents played a vital role in the Stalag Luft III escape.

Two of the three who made it home used fake papers claiming that they were Norwegian electricians working in Germany allowing them to evade detection as they made their way across occupied Europe.

Butler, head of military records at the archives, said that in addition to requests for materials, the secret letters were also used to provide information to MI9 about other PoWs who might be viewed as suitable candidates for intelligence work or the planning of escapes.

Other items featured in the exhibition include materials smuggled the other way into the camps in parcels to help escape efforts.

These include a playing card with maps hidden in them or a hairbrush with a map and a saw concealed inside.

The audacious breakout from Stalag Luft III might have captured the public's imagination, but a lesser known escape of 70 German prisoners from a camp in Wales also features in the exhibition.

The escapers tunnelled under three lines of barbed wire in March 1945 before being captured and returned.

Other stories featured include those who "mentally escaped" with activities ranging from theatre to drawing such as British author and playwright PG Wodehouse and artist Ronald Searle.

Wodehouse wrote at least one novel while a prisoner in an internment camp in Nazi-occupied territory while Searle produced over 300 sketches of his fellow PoWs in Changi camp in Singapore and working on the Thai-Burma railway.