In the early 1990s, marine researchers in the Caribbean found something alarming. On reef after reef, corals were dying off – and seaweed was growing in their place.

Since then, this pattern has been observed on reefs around the world: as corals die, seaweed takes over.

Once seaweed gets a foothold, it’s hard for coral to compete. These large, fleshy algae can quickly come to dominate. As the oceans heat up and reefs degrade, the trend is expected to accelerate. Former coral reefs will become dominated by seaweed instead, with cascading damage to reef ecosystems.

This shift hasn’t happened widely on the Great Barrier Reef – yet. But there are worrying signs of seaweed takeover on some reefs, including those fringing Yunbenun (Magnetic Island).

We wondered – what if you could help corals by weeding out intruding seaweed? In our new research, we found sea-weeding actually worked, giving coral time to recover.

Of course, this is a stopgap measure. It’s designed to buy time while we tackle the main threats to the world’s largest reef system – notably, climate change.

How can seaweed take over?

Corals don’t like hot water, sediment or an overload of nutrients. So when there’s a mass bleaching or coral death event after a marine heatwave or cyclone, there’s empty space on the reef.

Seaweeds are similar to weeds in a garden. They can colonise quickly, grow fast and tall, soaking up sunlight and competing directly with surviving corals for light and space.

Once these tough algae establish, corals struggle to come back. Then there are feedback loops which can further prevent coral return – coral larvae are put off by chemicals emitted by seaweed. Seaweed growth takes the space where coral larvae could have settled. And the health of adult corals can be hit by algae just living nearby. It’s safe to say coral and algae are not best friends.

Read more: Is the Great Barrier Reef reviving – or dying? Here's what's happening beyond the headlines

You might wonder why nature doesn’t even the balance. At Yunbenun, the main genus of seaweed is Sargassum, most famous for their massive blooms in the Sargasso Sea. The problem is, not many fish like the taste. When Sargassum is fully grown, it’s especially unpalatable to herbivorous fish.

Many fish will actively avoid areas with long, dense growth of seaweed for fear of predators hiding among the foliage.

Weeding the sea

So if grazing fish won’t eat the problem, and urchins aren’t very abundant, it’s up to us. We set about testing sea-weeding, where you dive down and cut back stands of macroalgae. Would the corals bounce back?

The process is just like weeding a garden, but underwater. You dive down, yank fronds of seaweed off the seafloor and dispose them back on shore. It’s labour intensive, but simple. We were aided in weeding by citizen scientists through Earthwatch Institute.

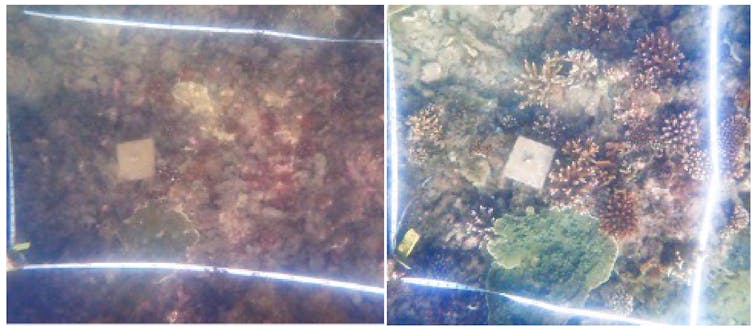

It took three years, and the removal of three tonnes of seaweed, but it worked. In the areas we’d weeded (300m², or about 1% of the seafloor at our study site) twice or three times a year, the coral had made a spectacular recovery. Corals now covered between 1.5 to six times the area they had before.

After the coral returned, seaweed has been growing back less and less. Seaweed originally covered 80% of the seafloor, but now covers less than 40%. That suggests it might need only a few years of effort to suppress the seaweed and push the coral ecosystem toward recovery.

Importantly, the diversity of coral species increased too – and that means weeding isn’t favouring any single coral species.

We disposed of the seaweed in a local school’s organic compost heap. While not part of this project, there is promising new research showing macroalgae like Sargassum could be a carbon sink. Seaweed has many uses, ranging from bio-plastics, fertiliser or biofuels. If the economics stack up, removing mature macroalgae could provide a win-win for reef and climate health – even if it’s only small scale.

Where would this approach be most useful?

On the Great Barrier Reef, the reefs most prone to seaweed takeover are those near to shore. These are, as you’d expect, also the most accessible and the ones most often visited by tourists.

If you were going to use this technique more widely, it would make sense, therefore, to focus on nearshore reefs. They’re economically important for industries like tourism and fishing.

At present, there’s a lot of research being done on high-tech interventions such as breeding corals to tolerate hotter water, or brightening clouds. What we hope to show is the equal value of testing low-tech, low-cost methods which can achieve scale by harnessing citizen science volunteers and community programs. This has the added advantage of building public support and giving concerned citizens a clear way to help. It could be useful not only in Australia, but on island nations in the Pacific with limited resources.

By our estimates, the cost – around A$104,000 per hectare – is a fraction of other reef restoration techniques, which have a median cost of about $616,000 per hectare, ranging all the way up to $6.2 million per hectare.

This isn’t a silver bullet. We have no reef restoration or management approaches able to keep our reefs alive if we don’t tackle the big issues – hotter, more acidic seas brought about by climate change, as well as nutrient runoff and other threats.

So what role could sea-weeding have? Even if we manage to significantly cut emissions globally in the coming decades, there’s so much CO₂ already in the atmosphere that reefs will keep deteriorating.

That means there could well be a role for this approach. This low-tech but rapidly effective technique could help keep corals alive while we work for decisive action on climate change.

Read more: Accelerated evolution and automated aquaculture could help coral weather the heat

Hillary Smith receives funding from a partnership between Earthwatch Institute and Mitsubishi Corporation, as well as the National Geographic Society, the British Ecological Society, the Reef HQ Volunteer Association, and the Women Diver Hall of Fame. She is a 2019 National Geographic Explorer, and is affiliated with James Cook University and the University of New South Wales.

David Bourne receives funding from a partnership between Earthwatch Institute and Mitsubishi Corporation. He is affiliated with James Cook University and the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.