“Hello to all you lovely lesbians out there! My name is Debbie, and I’m here to show you a few things about taking care of your vaginal health.”

So opens the first “Lesbian Health” segment on “Dyke TV,” a lesbian feminist television series that aired on New York’s public access stations from 1993 to 2006.

The half-hour program focused on lesbian activism, community issues, art and film, news, health, sports and culture. Created by three artist-activists – Cuban playwright Ana Simo, theater director and producer Linda Chapman and independent filmmaker Mary Patierno – “Dyke TV” was one of the first TV shows made by and for LGBTQ women.

While many people might think LGBTQ+ representation on TV began in the 1990s on shows like “Ellen” and “Will & Grace,” LGBTQ+ people had already been producing their own television programming on local stations in the U.S. and Canada for decades.

In fact my research has identified hundreds of LGBTQ+ public access series produced across the country.

In a media environment historically hostile to LGBTQ+ people and issues, LGBTQ+ people created their own local programming to shine a spotlight on their lives, communities and concerns.

Experimentation and advocacy

On this particular health segment on “Dyke TV,” a woman proceeds to give herself a cervical exam in front of the camera using a mirror, a flashlight and a speculum.

Close-up shots of this woman’s genitalia show her vulva, vagina and cervix as she narrates the exam in a matter-of-fact tone, explaining how viewers can use these tools on their own to check for vaginal abnormalities. Recalling the ethos of the women’s health movement of the 1970s, “Dyke TV” instructs audiences to empower themselves in a world where women’s health care is marginalized.

Because public access TV in New York was relatively unregulated, the show’s hosts could openly discuss sexual health and air segments that would otherwise be censored on broadcast networks.

Like today’s LGBTQ content creators, many of the producers of LGBTQ+ public access series experimented with genre, form and content in entertaining and imaginative ways.

LGBTQ+ actors, entertainers, activists and artists – who often experienced discrimination and tokenism on mainstream media – appeared on these series to publicize and discuss their work. Iconic drag queen RuPaul got his start performing on public access in Atlanta, where “The American Music Show” gave him a platform to promote his burgeoning drag persona in the mid-1980s.

The producers often saw their series as a blend of entertainment, art and media activism.

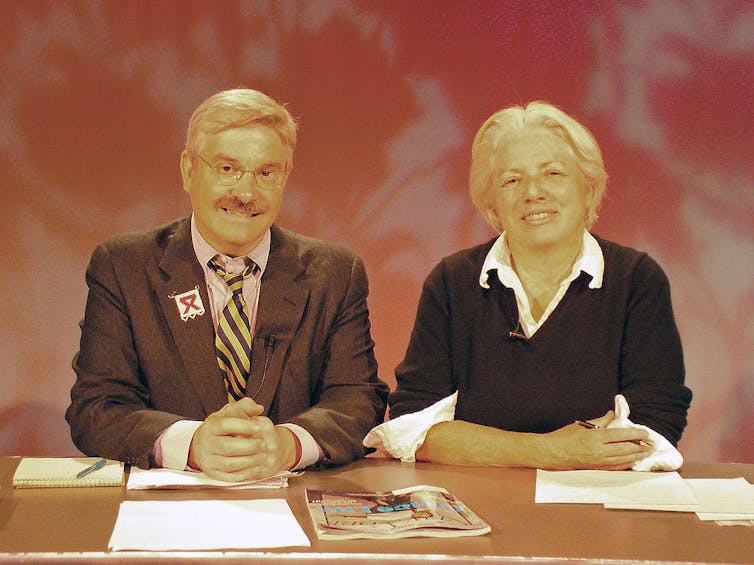

Shows like “The Gay Dating Game” and “Be My Guest” were tongue-in-cheek satires of 1950s game shows. News programs such as “Gay USA,” which broadcast its first episode in 1985, reported on local and national LGBTQ news and health issues.

Variety shows like “The Emerald City” in the 1970s, “Gay Morning America” in the 1980s, and “Candied Camera” in the 1990s combined interviews, musical performances, comedy skits and news programming. Scripted soap operas, like “Secret Passions,” starred amateur gay actors. And on-the-street interview programs like “The Glennda and Brenda Show” used drag and street theater to spark discussions about LGBTQ issues.

Other programs featured racier content.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, “Men & Films,” “The Closet Case Show” and “Robin Byrd’s Men for Men” incorporated interviews with porn stars, clips from porn videos and footage of sex at nightclubs and parties.

Skirting the censors

The regulation of sex on cable television has long been a political and cultural flashpoint.

But regulatory loopholes inadvertently allowed sexual content on public access. This allowed hosts and guests to talk openly about gay sex and safer sex practices on these shows – and even demonstrate them on camera.

The impetus for public access television was similar to the ethos of public broadcasting, which sought to create noncommercial and educational television programming in the service of the public interest.

In 1972, the Federal Communications Commission issued an order requiring cable television systems in the country’s top 100 markets to offer access channels for public use. The FCC mandated that cable companies make airtime, equipment and studio space to individuals and community groups to use for their own programming on a first-come, first-serve basis.

The FCC’s regulatory authority does not extend to editorial control over public access content. For this reason, repeated attempts to block, regulate and censor programming throughout the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s were challenged by cable access producers and civil liberties organizations.

The Supreme Court has continually struck down laws that attempt to censor cable access programming on First Amendment grounds. A cable operator can refuse to air a program that contains “obscenity,” but what counts as obscenity is up for interpretation.

Over the years, producers of LGBTQ-themed shows have fiercely defended their programming from calls for censorship, and the law has consistently been on their side.

Airing the AIDS crisis

As the AIDS crisis began to devastate LGBTQ+ communities in the 1980s, public access television grew increasingly important.

Many of the aforementioned series devoted multiple segments and episodes to discussing the devastating impact of HIV/AIDS on their personal lives, relationships and communities. Series like “Living with AIDS”, “HoMoVISIONES” and “ACT UP Live!” were specifically designed to educate and galvanize viewers around HIV/AIDS activism. With HIV/AIDS receiving minimal coverage on mainstream media outlets – and a lack of political action by local, state and national officials – these programs were some of the few places where LGBTQ+ people could learn the latest information about the epidemic and efforts to combat it.

The long-running program “Gay USA” is one of the few remaining LGBTQ+ public access series; new episodes air locally in New York and nationally via Free Speech TV each week. While public access stations still exist in most cities around the country, production has waned since the advent of cheaper digital media technologies and streaming video services in the mid-2000s.

And yet during this media era – let’s call it “peak public access TV” – these scrappy, experimental, sexual, campy and powerful series offered remarkable glimpses into LGBTQ+ culture, history and activism.

Lauren Herold does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.