Under a doctrine established in the 1984 case Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, courts defer to a federal agency's "permissible" or "reasonable" interpretation of an "ambiguous" statute. As became clear during oral arguments in two Supreme Court cases challenging Chevron deference on Wednesday, that principle poses several puzzles, starting with the meaning of ambiguous.

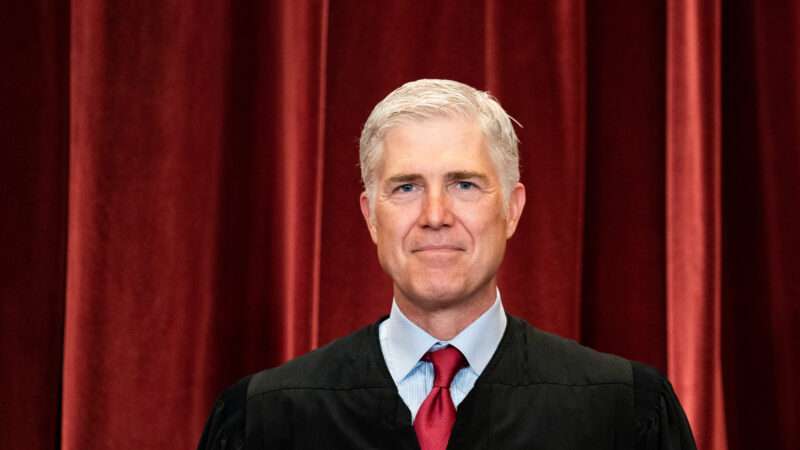

At least four justices—Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neal Gorsuch, and Brett Kavanaugh—have criticized the doctrine for allowing bureaucrats to usurp a judicial function, and their skepticism was clear from the questions they posed to Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar. Only three justices—Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor, and Ketanji Brown Jackson—were clearly inclined to stick with a rule that in practice empowers agencies to rewrite the law and invent their own authority.

The two cases, Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless v. Department of Commerce, both involve the question of whether herring fishermen can legally be forced to subsidize the salaries of on-board observers who monitor compliance with fishery regulations. The relevant statute explicitly authorizes the collection of such fees, within specified limits, from a few categories of fishing operations, but those categories do not include the New Jersey and Rhode Island businesses that filed these lawsuits.

Under Chevron, Prelogar argued, the National Marine Fisheries Service has the discretion to fill the "gap" left by congressional silence. The lawyers representing the plaintiffs, former Solicitor General Paul Clement and Washington, D.C., attorney Roman Martinez, argued that such deference violates due process, the separation of powers, and the rule of law by systematically favoring the executive branch's interpretation of any statute that might be viewed as "silent or ambiguous" on a point of contention between federal agencies and the people who have to deal with them.

"There is no justification for giving the tie to the government or conjuring agency

authority from silence," Clement said during his opening statement in Loper Bright. "Both the [Administrative Procedure Act] and constitutional avoidance principles call for de novo review, asking only what's the best reading of the statute. Asking, instead, 'is the statute ambiguous?' is fundamentally misguided. The whole point of statutory construction is to bring clarity, not to identify ambiguity." That approach, he added, is "unworkable" because "its critical threshold question of ambiguity is hopelessly ambiguous."

Gorsuch, who has been notably critical of the Chevron doctrine as a justice and an appeals court judge, and Kavanaugh, another critic of the precedent, zeroed in on that last point while questioning Prelogar during oral arguments in Relentless. "How would you define ambiguity?" Kavanaugh asked. "How would you, if you were a judge, say, 'yes, this is ambiguous' or 'no, that's not ambiguous'?"

Prelogar's response: "A statute is ambiguous when the court has exhausted the tools of interpretation and hasn't found a single right answer." She said judges should ask, "Did Congress resolve this one? Do I have confidence that actually I've got it, [that] I understand what Congress meant to say in this statute?" Applying that approach, she said, a court might conclude that "the right way to understand this statute is that it's conferring discretion on the agency to take a range of permissible approaches."

Kavanaugh asked Prelogar if she thought "it's possible for a judge to say, 'The best reading of the statute is X, but I think it is ambiguous, and, therefore, I'm going to defer to the agency, which has offered Y.'" When she said no, Kavanaugh was openly incredulous: "That can't happen? I think that happens all the time."

In response, Prelogar said "there are two different ways in which courts use the term 'best interpretation of the statute.'" A judge might "apply all of the tools" of statutory interpretation, as he is supposed to do under Step 1 of a Chevron analysis, and conclude that "Congress spoke to the issue." In that case, Prelogar said, even if "there's some doubt" about the correct reading of the law, a judge is not required to accept the agency's interpretation merely because it is "permissible." But if the judge decides "Congress hasn't spoken to the issue," she said, "filling the gap" is left to the agency's discretion, even if the judge "would have done it differently" as a matter of policy.

Gorsuch suggested that Prelogar had presented "two very different views" of a judge's function under Chevron. Under one approach, "there is a better interpretation," and the judge applies it. Under the other approach, the judge "defer[s] anyway given whatever considerations you want to throw into the ambiguity bucket." Some judges, he noted, "claim never to have found an ambiguity," while "other, equally excellent circuit judges have said they find them all the time."

Martinez noted that 6th Circuit Judge Raymond Kethledge falls into the first category, while the late D.C. Circuit Judge Laurence Silberman fell into the second. "If there's that much disagreement," Martinez said, "that's a sign that Chevron really isn't workable."

Prelogar suggested that the justices could respond to such widely varying understandings of ambiguity by reminding the lower courts that they are not supposed to give up on statutory interpretation just because it is difficult to choose between contending views. Gorsuch noted that the Supreme Court had delivered that message around "15 times over the last eight or 10 years," telling judges they should "really, really, really go look at all the statutory [interpretation] tools." Yet even in "this rather prosaic case," he said, one appeals court "found ambiguity," while the other arguably "tried to resolve it at Step 1," which suggests judges "can't figure out what Chevron means."

In short, while Prelogar argued that Chevron promotes uniformity by constraining judges from reading their own policy preferences into the law, Gorsuch et al. argued that it has the opposite effect. As Gorsuch put it in 2022, "all this ambiguity about ambiguity" has allowed courts to apply what Kavanaugh described, in a 2016 law review article, as "wildly different conceptions of whether a particular statute is clear or ambiguous."

Sotomayor noted that she and her colleagues frequently disagree about how best to interpret a statute, leading to narrowly decided cases that come down on one side or the other. "If the Court can disagree reasonably and come to that tie-breaker point," she asked Martinez, "why shouldn't deference be given" to an agency with "expertise," experience with "on-the-ground execution," and "knowledge of consequences"? That account of what Chevron requires, Martinez replied, implies that a statute is "ambiguous because reasonable people can disagree" about its meaning, which confirms that the doctrine assigns a judicial function to executive agencies.

Prelogar also argued that preserving Chevron would promote "stability" and "predictability," noting that both legislators and regulators have come to rely on the assumption that agencies have broad discretion in filling gaps and resolving ambiguity. Overturning Chevron, she said, would be an "unwarranted shock to the legal system." But Gorsuch et al. argued that Chevron actually has undermined stability by allowing agencies to overrule judicial interpretations and "flip-flop" between different readings of a statute, depending on the agenda of any given administration.

The "best example" of the latter, Clement told the justices, is the question of whether broadband internet companies are offering a "telecommunications service" or an "information service," which has a crucial impact on the regulatory authority of the Federal Communications Commission. Gorsuch brought up the same example, noting that the Supreme Court had deferred to the Bush administration's view of the matter, saying "you automatically win." But then the Obama administration "came back and proposed an opposite rule," which the Trump administration reversed. And "as I understand it," Gorsuch added, the Biden administration "is thinking about going back to where we started."

Big businesses, Gorsuch noted, have the resources to keep up with such shifting statutory interpretations and influence the process, which can result in "regulatory capture," since "there's a lot of movement from industry in and out of those agencies." In Chevron itself, the Supreme Court deferred to an agency interpretation that benefited regulated companies. "I don't worry…about those people," Gorsuch said. "They can take care of themselves."

Gorsuch contrasted that situation with "cases I saw routinely" as a 10th Circuit judge, which involved "the immigrant, the veteran seeking his benefits, the Social Security disability applicant." Those supplicants, he noted, "have no power to influence the agencies" and "will never capture them," and their interests "are not the sorts of things on which people vote, generally speaking." Gorsuch said he had yet to see a case "where Chevron wound up benefiting those kinds of people." He said it therefore looks like the Chevron doctrine has a "disparate impact on different classes of persons." In other words, the doctrine tends to screw over the little guy—an argument that Gorsuch said was "powerfully" raised by the plaintiffs in Relentless and Loper Bright, who complain that the contested regulatory fees amount to about a fifth of the revenue earned by their family-owned businesses.

Kagan, Sotomayor, and Jackson, by contrast, amplified Prelogar's argument that agency experts are best situated to fill in the gaps left by Congress when it passes legislation. Kagan suggested that judges are not qualified to resolve issues such as whether "a new product designed to promote healthy cholesterol levels" should be treated as a strictly regulated "drug" or a lightly regulated "dietary supplement." She also cited regulation of artificial intelligence as an area where Congress might reasonably choose to let agencies decide the details. Given the rapid and unpredictable pace of A.I. developments, she said, "there are going to be all kinds of places where, although there's not an explicit delegation, Congress has in effect left a gap" or "created an ambiguity."

Jackson likewise said she viewed Chevron as "helping courts stay away from

policy making." If the decision were overruled, she worried, "the Court will then

suddenly become a policy maker by majority rule or not, making policy determinations."

Both sides agreed that Congress can explicitly give agencies broad leeway—for example, by authorizing "reasonable" or "appropriate" regulations. But they disagreed about what should happen when Congress is silent. In that situation, "the delegation is fictional," Martinez argued. "There's no reason to think that Congress intends every ambiguity in every agency statute to give agencies an ongoing power to interpret and reinterpret federal law in ways that override its best meaning."

Gorsuch raised the same objection. "You've said that it doesn't matter whether Congress actually thought about it," he told Prelogar. "There are many instances where Congress didn't think about it. And in every one of those, Chevron is exploited against the individual and in favor of the government."

The post SCOTUS Ponders the Ambiguity of 'Ambiguous' and Other <i>Chevron</i> Doctrine Puzzles appeared first on Reason.com.