The next El Niño can be predicted more than two years in advance, according to a new study that looked at thousands of years of past climate data.

The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a climate cycle that is characterized by the cooling (La Niña) and warming (El Niño) of the sea surface above the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. It is one of the strongest and most predictable weather patterns affecting the global climate. Using various climate models, scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have been forecasting ENSO events about six to 12 months in advance. But the new study, published June 16 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, more than doubles that prediction window in some instances.

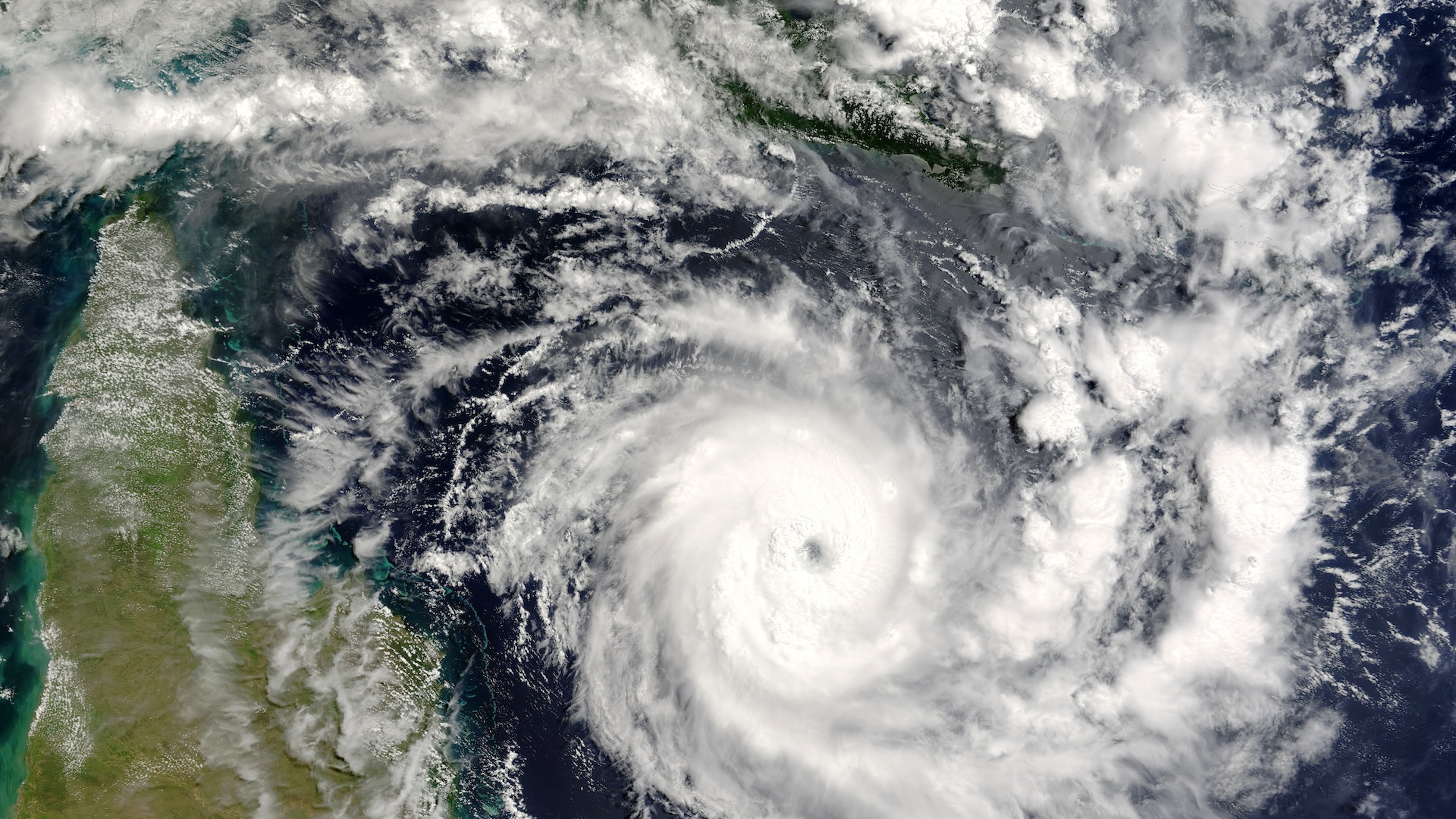

In the contiguous U.S., both El Niño and La Niña influence hurricanes in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Like a seesaw, La Niña weakens hurricane activity in the eastern Pacific and strengthens it in the Atlantic. El Niño does the opposite. And strong El Niño events typically mean wet weather for the U.S. Southwest, while La Niña typically presages hot, dry conditions in the same region.

Predicting the weather more than a few weeks out is challenging, but "when the ocean or land surface or ice gets involved, we can get some longer predictability because these processes evolve more slowly," study lead author Nathan Lenssen, a climatologist at the Colorado School of Mines and a project scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, told Live Science.

Related: What is El Niño?

When it comes to predicting ENSO, "the longer lead time we have on any of those, the better," Emily Becker, a climate scientist at the University of Miami who was not involved in the study, told Live Science. ENSO prediction is valuable for emergency planning and resource management, she said. For instance, if drought conditions are likely in the next few years, state governments can enact water-sparing or storage plans in advance.

However, few studies have tried to predict El Niño or La Niña more than a year in advance.

To test whether such predictions were trustworthy, Lenssen and his team looked at 10 sophisticated models that drew on hundreds to thousands of years of data on sea level, air temperature, rainfall and more to simulate the climate. The models were essentially recreating a specific point in time —say, January 2000—and trying to forecast the climate for the next three years—2000, 2001 and 2002—without additional information. The models also showed whether El Niño, La Niña or a neutral state was likely in those 36 months.

The research team assessed how well these models predicted ENSO against historical records from 1901 to 2009.

They found that ENSO is most predictable following strong El Niño events, such as the ones in 1997 and 2016. Moreover, their work showed that those forecasts could be made at least two years in advance. Multiyear predictions were less reliable during a weak El Niño or La Niña or in-between "neutral" events.

"I think that this paper had a really thorough and comprehensive approach," Becker told Live Science.

Climate forecasting centers haven't released longer-term predictions yet, but Lenssen and his team are in discussions with international agencies to see when or whether such long-term ENSO forecasts should be issued.