Our planet's rivers are like our planet's arteries. They're woven across the globe in intricate networks, ferrying life-sustaining freshwater around the world. Rivers aren't just our own lifelines, providing us with the drinking water we need to survive, but their freshwater reserves are also the primary lifelines of 10 percent of all known animals and half of all known fish species, helping sustain healthy and diverse ecosystems. They are, in short, the most renewable, accessible and thus sustainable storehouses of freshwater we have.

Yet, humans have a surprisingly limited understanding of how much water Earth’s rivers hold and how fast that water moves — two features key to managing our planet's precious freshwater resource.

Cedric David, a scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California likens the situation to spending money from a checking account without knowing the balance.

Related: NASA's SWOT satellite maps nearly of all Earth's water (video)

"It's like we've had some idea of how much we're making and how much we're spending, but we didn't know how much was in the account," he told Space.com.

Much of current literature surrounding rivers references 50-year-old estimates made by the Russian Academy of Sciences, outlined in a 1974 report published in Russian that was later translated to English in 1978. This is likely because updated estimates have been difficult to gather, particularly when it comes to rivers that are far from human populations. Even satellites cannot observe how much water flows into some rivers from the land, known as runoff, which is water resulting from rainfall leftover on the planet's surface that exceeds the land's absorption capacity. That surplus water then flows into nearby water bodies, including rivers.

River speeds are also hard to determine based on conventional "back of the envelope" formulas that are based on in-situ measurements from 50 years ago, David told Space.com. In late April, David and a team of NASA researchers embarked on a quest to provide the best estimates yet of just how much water flows through Earth's rivers, the rates at which it flows into oceans and how much both figures have changed over time.

"We are able to revisit some good old numbers with some tricks that even we didn't know were possible," said David. "We did what we could to fix everything we could based on the limited observations we have."

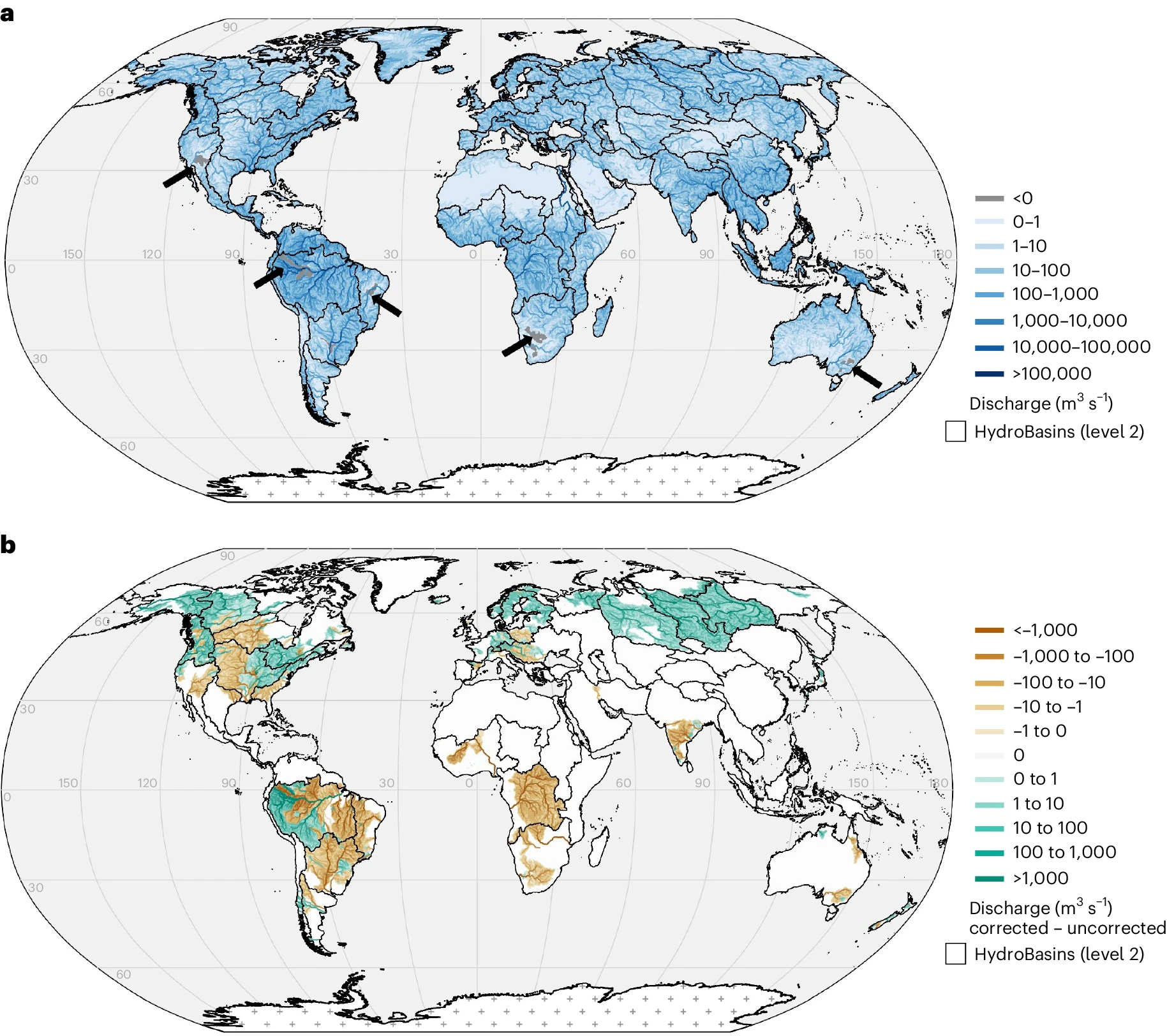

By using previous satellite data to model runoff levels associated with rivers on a map, the researchers found that, from 1980 to 2009, the total volume of water in Earth's rivers was 539 cubic miles (2,246 cubic kilometers) on average, which is about half of Lake Michigan's water volume. The Amazon River Basin, which extends from the Andes Mountains in Peru to the Atlantic coast of Brazil, holds 38 percent of all Earth's water, according to the study, which was published last month in Nature Geoscience. That same basin also dumps the most water into the ocean — about 1,629 cubic miles (6,789 cubic kilometers) per year, or 18 percent of the total discharge to the ocean worldwide.

"I was hoping to demonstrate to myself that there is a lot more river water than we thought," said David. "Turns out, that's not what we got — that's a little sobering."

The new dataset, which covers 30 percent of the planet, consists of in-situ measurements and computer models accounting for nearly 3 million river segments worldwide. It also brings to light rivers that have depleted due to overuse by humans. Climate change, irrigation projects and other landscape-modifying actions are likely affecting water supply in multiple rivers, including the Colorado River basin in the United States, the Amazon basin in South America, the Murray-Darling basin in Australia and the Orange River basin in southern Africa.

"We're trying to give data for people to make smart decisions and start some conversations," said David. To aid that goal, the new dataset and the study is open access, meaning it is free for anyone to read online. "We're hoping it might make a little bit of a difference," he said.

He also noted the value of open science in aiding interesting scientific research as a whole.

The work that resulted in the new paper began in early 2022, when the study’s lead author, Elyssa Collins, came across a publicly available code for a climate model David had shared online. After a few months of tinkering with the code, Collins, now a doctoral student at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, reached out to David with a few ideas, an enterprising effort that resulted in a six-month internship under David at the JPL's location in Pasadena, California. "This is just one of the many success stories [of open science] — if you give stuff for free, some cool stuff happens," said David. "It's so important that we learn from each other, that we share, that we include everybody that cares in the science we do."

In the coming years, the researchers plan to compare their latest estimates, which are based on computer models, to upcoming satellite data from NASA's Surface Water and Ocean Topography mission, or SWOT, to improve estimates of human footprint on our planet's water cycle.

"You can think of it as camera images but they just tell you the elevation of water," David said of SWOT's data. The satellite, which has been mapping the heights of water surfaces on Earth since December 2022, is helping scientists calculate the changes in height of the river, from which they estimate how much water is present and discharged. Last month, the satellite captured the depth of a temporary, shallow lake that sprouted for several weeks at the bottom of Death Valley National Park, which spans the California and Nevada border and is the hottest place on Earth. The 1-foot-deep (0.3-meter-deep) lake, dubbed Lake Manly, is spread across more area than expected for such a body of water due to strong winds, allowing SWOT to study the happenings in a region without permanent, dedicated instruments.

Other early results show SWOT's water-height data can also fill gaps in the literature about evolving conditions during and after floods, which satellites that usually just image flooded areas usually cannot capture, and improve flood predictions.

In addition to SWOT, over 30 NASA satellites currently record data of Earth's land surface, ice, oceans and atmosphere. They're there as part of an effort the agency began in the 1980s, an effort dedicated to gleaning the data necessary to understand and forecast the weather, of course, but also to monitor cyclones, floods, wildfires and other devastating changes to the planet's climate that are exacerbated by human activities like burning coal. Offering us a view of Earth at scales that could never be achieved on the ground, these satellites are helping scientists keep an eye on animals vulnerable to habitat loss, search for signs of potential volcanic eruptions, decode the altered chemistry of coastal waters and track rates of declining sea ice.

"It's relatively underappreciated how much Earth science we do at NASA," David told Space.com. In fact, half of all science done at JPL is Earth science, he said.

"We don't have a Planet B — this is it for a long time."