Notes on a New Zealand childhood in the sticks in Hawkes Bay It seems to me there are long periods of childhood that can be divided into two distinct categories: school and school holidays. School holidays can then be subcategorised further, into at home and away. Up until I was around the age of 10, at home often entailed being dropped off in the morning with our dad’s parents. Days of trailing around after Nana or Grandad in the garden. Puttering around with glue, nails and some piece of wooden furniture, usually a chair, in the garage. Occasionally a mid-morning amble to the Epuni bakery for Neenish tarts.

Away was less predictable. At the time my poem "Shooting rats" [below] is set, I was the resentful youngest member of a blended household, reconstituted – just add water! – from the damaged leftovers of two previously shattered families. The Brady Bunch we were not. Yet every summer, at the adults’ insistence, we’d wedge ourselves – six humans, the dog, our backpacks, sports bags and tents of varying quality and size – into the Vauxhall Cresta – hot vinyl seats and no aircon – and head for the hills for a three-week camping holiday.

If we went north – we mostly did, as it was cheaper than going south – we’d invariably end up in rural Hawkes Bay, visiting with my Uncle’s family. In stark contrast to our urban uptightness, they were laidback country folk. They offered a warm welcome, the opportunity to hang out with our cousins and, better still, their friendly, kid-loving dogs.

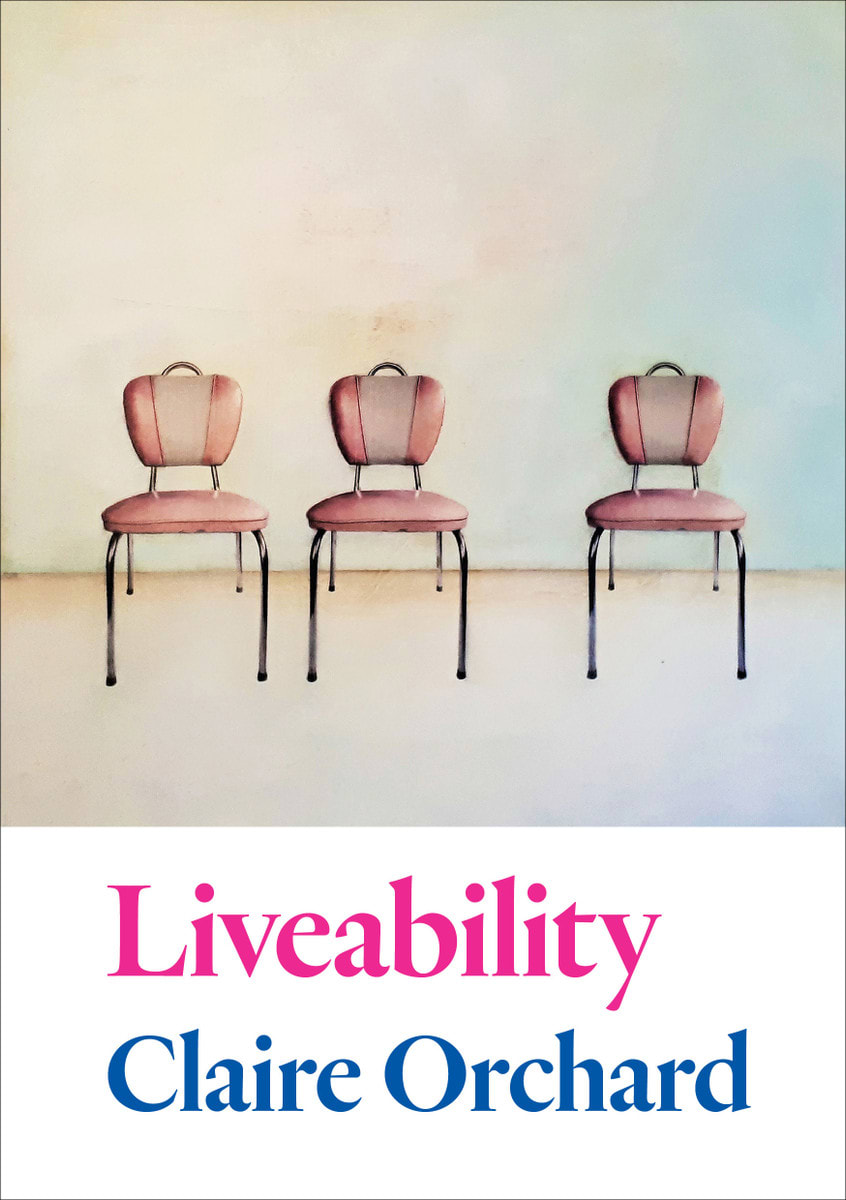

"Shooting rats", from my new book Liveability, was inspired by a memory from one of those summer visits. I asked my brother what he remembers about going shooting with Jim. It turns out the poem is at odds with most of his recollections. We’d have been going to the tip, if we were shooting rats, he says. Was more likely rabbits, if we were on a hillside. He did have a ute, but usually we went shooting at dusk, not in the middle of the day. I did get the bit about the farmer’s grass right, at least. There ensues a description of gun type and bullet calibre the goes right over my head. A tale of the time the two of them went through the Lindsay Tunnel – dark, quiet and claustrophobic.

If I’m honest, the only triggers I can hand on heart say I’ve ever actually pulled were on super-soakers or nerf guns. I’ve never had any interest in killing small furry animals. I was just along for the ride. But to this day, if I close my eyes and summon it, I can see that ridgeline approaching, feel the energy and motion of the ute bounding up that hill, the green grass disappearing on either side, the sheep scattering, the sensation of space opening up. And then the macrocarpa are there, lifting their shaggy arms to the sky, not framing it but saluting it, their giant limbs dwarfed by the scale of the blue above. That feeling of elation at experiencing immensity, the momentary lifting of the spirit with the appreciation of possibility. That’s the bedrock of truth of it.

Shooting rats

Uncle Jim drove the ute

and the dogs sat up eager in the tray

with the guns. Ten k’s out of town

we turned off tarmac onto a farmer’s

wet grass and up, up, we lolloped,

scattering sheep, eating

the juicy curves of the hillside

with all four wheels wide open until

reaching the top felt like flying

and when we looked we saw

through limbs of thinned macrocarpa

the sky, too, was planning something big.

The poetry collection Liveability by Claire Orchard (Te Herenga Waka University Press, $25) is available in bookstores nationwide.