Retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor, the first woman to serve on the court, died Friday in Phoenix, Ariz., of complications related to advanced dementia, probably Alzheimer's, and a respiratory illness, the court announced. She was 93 years old.

O'Connor was appointed to the court by President Reagan in 1981 and retired in 2006, after serving more than 24 years on the court.

O'Connor served on the court for a quarter of a century and, after that, became an outspoken critic of what she saw as modern threats to judicial independence, particularly the election of state judges, which she believed eroded independent judicial decision-making, and public confidence in the courts.

While on the court, O'Connor was called "the most powerful woman in America." Because of her position at the center of a court that was so closely divided on so many major questions, she often cast the deciding vote in cases involving abortion, affirmative action, national security, campaign finance reform, separation of church and state, and states' rights, as well as in the case that decided the 2000 election, Bush v. Gore — a decision she later hinted she regretted.

Her retirement allowed President George W. Bush to appoint a much more conservative justice, Samuel Alito, in her place, and that appointment took the court in a far more conservative direction.

O'Connor's retirement was the last step in a long balancing act between family and career. In 2005, O'Connor's husband was suffering from Alzheimer's disease, and when the ailing Chief Justice William Rehnquist told her that he was putting off his retirement, O'Connor decided that with her husband's health declining, she could not wait and risk the possibility that the court would have two vacancies at once.

As it turned out, that's what happened anyway. O'Connor announced her retirement, and the chief justice died weeks later. She stayed on for another six months while confirmation hearings proceeded, and in a cruel twist of fate, her husband's health took such a precipitous downward turn that he had to be placed in a home, and later died.

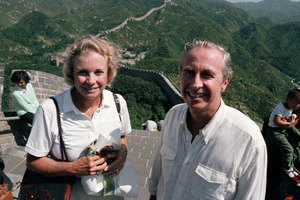

But on that June day in 2005 when O'Connor announced her retirement, she wept; she later made quite clear that she regretted the decision to step down. She went on to lead a multifaceted life, crisscrossing the United States and the rest of the world, crusading against threats to judicial independence and advocating for more civics instruction in public schools to teach students about the structure of the U.S. government.

A rising star

Born in Texas, O'Connor spent her early life riding horses and roping steers on the Lazy B, a 250-square-mile cattle ranch owned by her parents on the Arizona-New Mexico border.

At age 10, she was sent away to school in El Paso, and at age 16 she enrolled at Stanford, eventually graduating from law school third in her class.

On the job market, she soon learned nobody wanted to hire a female lawyer. After every job door was closed in her face, a desperate O'Connor finally made an offer to the San Mateo County attorney, an offer that she hoped he couldn't refuse.

"I wrote him a very long letter explaining all the reasons why I thought that I would be helpful to him in the office and offering to work for nothing, if that was necessary," O'Connor said in 2003 interview with NPR.

In the beginning it was indeed necessary; she worked for free and she even shared office space with the county attorney's secretary. But she soon was put on salary, and when she and her husband, John, moved to Arizona, she continued practicing law, stopping only when a dearth of babysitters forced a five-year hiatus to raise her three sons.

Soon she was a figure to be reckoned with in Arizona's political life. Elected to the state Senate, she quickly rose in Republican ranks to become the majority leader, and then was appointed a state trial judge and a state appellate court judge. By then, it was 1981, and with the retirement of Justice Potter Stewart, President Ronald Reagan had a Supreme Court vacancy to fill.

First female justice

Stewart's imminent retirement was known to only a few inside the administration, and there was initially something of a battle over whether the president should fulfill his campaign promise to appoint a woman.

Kenneth Starr, then an assistant to Attorney General William French Smith, recalls that staff aides examined Reagan's campaign words carefully, noting that he had not made an iron-clad pledge. Some administration insiders urged the president to use this first appointment to name Robert Bork or some other conservative luminary to the high court. But that was not to be.

"Reagan was not a word parser, and he felt that he had made a moral commitment to appoint a qualified woman to the Supreme Court, that it was long overdue ... and that's what our marching orders were," Starr said in an interview with NPR.

But back then, the list of qualified women with any conservative credentials at all was a short one. Starr believes that O'Connor's name was first suggested by then-Justice Rehnquist, a fellow Arizonan and a classmate of O'Connor's at Stanford. When O'Connor was spirited to the White House for an interview with Reagan, the two Westerners had an immediate rapport, and O'Connor soon won the nod.

O'Connor later acknowledged that her appointment was an "affirmative act" — that she was not among the most qualified judges or scholars back then. But still, she won quick confirmation.

An enormous impact on the law

Once on the court, O'Connor's main concern, she later said, was whether she could do the job. If she stumbled badly, she said, it would make life much more difficult for women.

As it turned out, of course, O'Connor's appointment gave a huge boost to women in the law.

"The minute I was confirmed and on the court, states across the country started putting more women ... on their Supreme Courts," O'Connor said. "And it made a difference in the acceptance of young women as lawyers. It opened doors for them."

In the years that followed, O'Connor's impact on the law would be enormous. On the court, she became part of a conservative states' rights majority, voting, for example, to strike down key portions of the Brady gun control law.

On the subject of racial discrimination and affirmative action, O'Connor was the key vote. In the 1980s and '90s, she wrote landmark court decisions limiting the use of affirmative action for minority contractors and invalidating the use of race as the predominant factor in drawing majority Black congressional districts. But a decade later, in 2003, O'Connor wrote the court's opinion declaring that colleges and universities are justified in using race as a factor in college and graduate school admissions.

"Such diversity promotes learning and better prepares students for an increasingly heterogeneous workforce, for responsible citizenship, and for the legal profession," O'Connor said then.

In each of the race cases, O'Connor followed a well-trodden path for her: decide the case before you, make as few broad and sweeping rules as possible, and leave the door open for future change in a different set of circumstances.

In 2004, she walked a similar careful line as author of the key decision on the president's power to detain enemy combatants at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Repudiating the Bush administration's position, she declared that even in wartime, the president does not have a "blank check" allowing him to indefinitely detain American citizens without charge and without a chance to rebut the government's allegations of wrongdoing.

"We conclude that a citizen detainee seeking to challenge his classification as an enemy combatant must receive ... a fair opportunity to rebut the government's factual assertions before a neutral decision-maker," O'Connor said when she announced the court's decision in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld.

A middle ground

In no area, though, was O'Connor more careful — and successful — at carving out a middle ground than on questions involving abortion. When she joined the court, a woman's right to an abortion was spelled out in Roe v. Wade as a relatively absolute right to privacy. But less than two years after becoming a justice, O'Connor dissented from a major extension of Roe, saying that in her view, a state could regulate abortions unless those regulations imposed an "undue burden" on a woman's right to choose.

Six years later, she deprived the court's four conservatives of a fifth vote to overturn Roe, but in a separate concurring opinion allowed more state restrictions on abortion. In 1992, the issue was back before the court and O'Connor, joined this time by Justices David Souter and Anthony Kennedy, voted to sustain what they called the "core" holding of Roe, a woman's right to an abortion, but using O'Connor's undue burden test.

"Some of us as individuals find abortion offensive to our most basic principles of morality, but that can't control our decision. Our obligation is to define the liberty of all, not to mandate our own moral code," O'Connor said in June of 1992 when she announced the court's decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. "We reaffirm the constitutionally protected liberty of the woman to decide to have an abortion before the fetus attains viability and to obtain it without undue interference from the state."

Eight years later, O'Connor provided the fifth and deciding vote on abortion, this time invalidating a so-called partial birth abortion law because it provided no exception to preserve the health of the mother, and thus imposed an undue burden. Within a year of her departure from the court, however, a new, more conservative court majority reached the opposite conclusion and upheld a federal ban on so-called partial birth abortions. It was a pattern that was to repeat itself in other areas of the law after O'Connor left.

When she was appointed to the Supreme Court, O'Connor knew she would be a role model for women. She persevered even through a bout with breast cancer. For a year, she wore a wig, looked drained and wan, but never missed a court day.

She presided over a period in American law when women moved from being anomalies in the courtroom to the majority of the graduates in many major American law schools. And she left a profound mark on the history of the Supreme Court and the nation.