Faced with the imminent possibility of a Russian invasion of Ukraine and what appears to be a deteriorating diplomatic stand-off, NATO and other western allies are again turning to sanctions in the absense of other viable options. Since the second world war governments around the world have turned to sanctions to solve their foreign-policy dilemmas on more than 700 occasions.

Recorded history notes sanctions going back as far as ancient Greece, when the Athenians banned merchants from nearby Megara because the Megarians had farmed land that was sacred to the Athenians and killed an Athenian herald. Megara enlisted the aid of Athens’ arch-rival Sparta, allegedly sparking the Peloponnesian War which brought Greece’s golden age to an end.

The League of sanctioners

But it was another cataclysmic conflict, the first world war, that brought the use of sanctions back into vogue. After the Armistice that brought the fighting to an end – and searching for an alternative to the violence that had claimed over 14 million lives – the leaders of the victorious powers devised the League of Nations to maintain international peace and empowered it with the right to prevent trade with any country that might threaten that peace.

As US president – a major player in the establishment of the league – Woodrow Wilson proclaimed:

A nation that is boycotted is a nation that is in sight of surrender. Apply this economic, peaceful, silent, deadly remedy and there will be no need for force. It is a terrible remedy. It does not cost a life outside the nation boycotted but it brings a pressure upon the nation which, in my judgment, no modern nation could resist.

The League achieved success in using sanctions to end conflicts between Yugoslavia and Albania, and Greece and Bulgaria. But it is their sanctions against Italy after its invasion of Abyssinia in 1935 (now known as Ethiopia) that are most remembered. Too weak and too tardy to stop the fascist aggression, they were widely seen as token resistance. The British government even went so far as to inquire if Mussolini would object to oil being included in the embargo. When Il Duce said he would, oil was exempted.

As former prime minister David Lloyd George said, the sanctions “came too late to save Abyssinia, but they are just in the nick of time to save [Her Majesty’s] Government”.

The Cold War brought a series of sanctions between the capitalist and communist worlds – but, because for the most part these two blocs did little trade with one another, the sanctions were typically more of an expression of displeasure than a policy with a plausibility of success. Moreover, sanctioned states could typically turn to rivals of the sanctioning countries who would be more than happy to trade with them.

Weapon of mass starvation?

Then, just as communism was collapsing, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. The invasion unified the United Nations (which was usually divided along ideological lines) against Iraq. Consequently the security council imposed what it said was the most comprehensive sanctions regime in history, requiring all members of the UN to block all trade with Iraq, except for food and medicine.

The goal of the sanctions was to convince Saddam to leave Kuwait but they were continued after the first Gulf War over concerns, subsequently shown to be baseless, that he was developing weapons of mass destruction.

To gain public support for lifting sanctions that were strangling his budget, the Iraqi government fabricated data suggesting that sanctions-induced malnutrition had claimed the lives of half a million children. Claims of causing civilian suffering were also made about the sanctions imposed on Haiti after the military coup that ousted the elected president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

Smart sanctions

This started the campaign for targeted sanctions. Previously, sanctions were applied haphazardly to entire economies with little thought for how they would affect the innocent civilian population. But the idea that sanctions designed to constrain ruthless despots were actually killing some of the very people they were meant to protect caused a sea change. Sanctions went from focusing on general prohibitions on imports and exports to focusing on asset freezes and travel bans of dictators and their henchmen.

But the effectiveness of this sort of sanctions have yet to be demonstrated. Autocrats are typically clever enough not to open accounts in their own names at banks under the jurisdiction of governments that are likely to sanction them. Nor are they often interested in vacationing in hostile territory, preventing these sanctions from having any bite.

SWIFT and severe

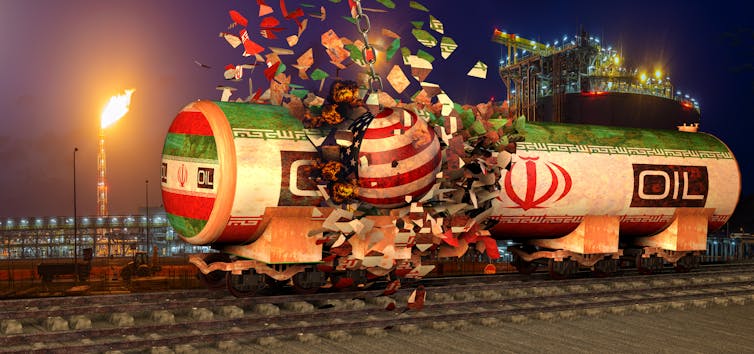

Nonetheless sanctions were being called upon to deal with the US and the EU’s most pressing foreign policy concerns, including preventing the Iranian government from obtaining a nuclear weapon. That’s when the western powers realised the leverage they really had.

While the US did little direct trade with Iran, international financial transfers for almost every country in the world ran through the SWIFT financial network, headquartered in Belgium. If Iranian banks were cut off from SWIFT it would be much more difficult for Iran to receive payment for its oil.

On March 23 2012 the Council of European Union ordered Iranian banks disconnected from the service and the Iranian economy went into freefall. Nonetheless it took over three more years for Iran to agree to a nuclear deal.

The western alliance is now considering that and more against Russia. Not only are they looking at removing Russia from SWIFT, they are also considering blocking Russia’s new Nord Stream 2 pipeline to export natural gas across Europe. They are even considering – symbolically – sanctioning Putin personally. But even this may not be enough to stop Russia from invading its neighbour.

Tyler Kustra does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.jpg?w=600)