Samuel Nichols Jr. won a full scholarship to the School of the Art Institute but felt it was his duty to get a job to help support his parents and five younger siblings.

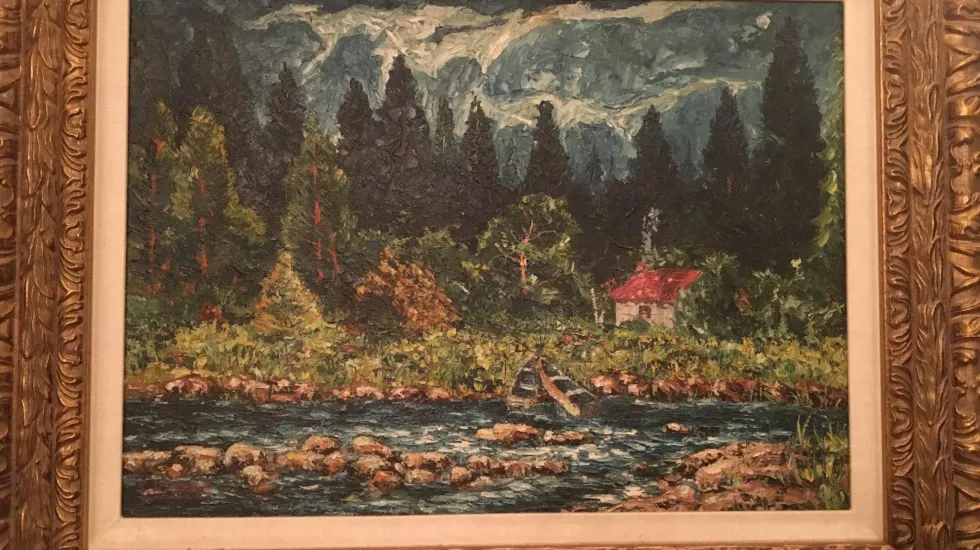

He ended up working for 44 years for the U.S. Postal Service, creating lobby displays and hand-lettered signs while also doing paintings commissioned by well-heeled clients who lived on the lakefront.

He grew up near 63rd Street and what’s now Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive. His father decided to move there on the advice of Carl Hansberry. The integration of that neighborhood helped inspire his daughter Lorraine Hansberry’s play “A Raisin in the Sun.”

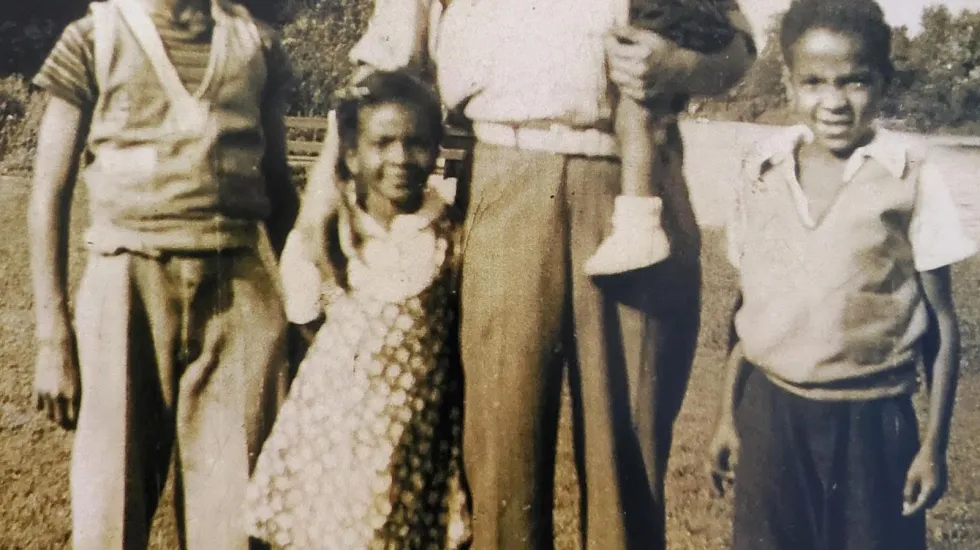

The playwright was a regular guest in the Nichols home because she was friends with Samuel Nichols’ sister Nichelle Nichols, who rocketed to fame as an actor as Lt. Nyota Uhura on TV’s original “Star Trek.”

Mr. Nichols, who died March 31 at 93, lived to see five grandchildren.

He and his wife Velma were married for nearly 68 years. He’d first noticed her in church. And, as an artist trained to be observant, he figured out her name from the mail she pulled from her purse to fan herself on a hot day.

She said Mr. Nichols was easy to talk to and kind. They took walks along the lake and ate ice cream. They visited the Art Institute, the Field Museum and the Adler Planetarium.

He was respectful.

“He sat on his side of the car under the steering wheel; I sat on the other side of the car,” Velma Nichols said. “And he kept his hands to himself.

“He was a good person,” she said. “He was my type.”

Mr. Nichols served as a deacon at their church, Shiloh Seventh-Day Adventist, 7000 S. Michigan Ave., for more than half a century.

“He was a monkey-wrench, duct-tape, do-it-yourself, fix-it-yourself, God-fearing Christian man,” said their son Franz.

Mr. Nichols’ life might have gone differently if not for the quick thinking of his parents when they lived in Robbins in the early 1930s.

Samuel Nichols Jr. was just a toddler when a dangerous man in a homburg hat and pinkie ring pulled up to their door in a black limousine. His father, also named Sam, told his wife Lishia Mae to keep the children quiet, as Nichelle Nichols described what happened in her 1994 autobiography “Beyond Uhura.”

“My name’s Mr. Capone,” their visitor said, “and I’m here because my brother Al is very displeased with you, Sam.”

The bootlegger was angry about a gin mill being shut down in Robbins, where Sam Nichols Sr. was mayor.

Lishia Mae Nichols ushered little Sam and the other frightened kids in to the parlor of their south suburban home. Their visitor accused the mayor of being a traitor, telling Samuel Nichols Sr. he’d been given plenty in bribes via a police bagman.

“I never received a dime from that weasel, nor did he ever approach me about it!” the mayor told the gangster, according to the book. “My father helped found this town, and I’d rather die before I’d help it be corrupted, dammit!”

Nichelle Nichols wrote that her father convinced the man he was honest and it was the bagman who wasn’t. The mobster told his wife: “You can relax, sweetheart. Sam’s OK. For now.”

Lishia Mae Nichols, who was pregnant at the time with Nichelle, moved a pillow she held over her belly, revealing a hidden gun and telling the mobster: “It’s a damn good thing he is.”

Nichelle Nichols wrote that Capone’s brother told the mayor: “You’ve got yourself one helluva little lady there.”

Lishia Mae and Sam Nichols Sr. “encouraged us in anything we wanted to do and backed us in anything we wanted to become,” Nichelle Nichols said in an oral history interview with The HistoryMakers website.

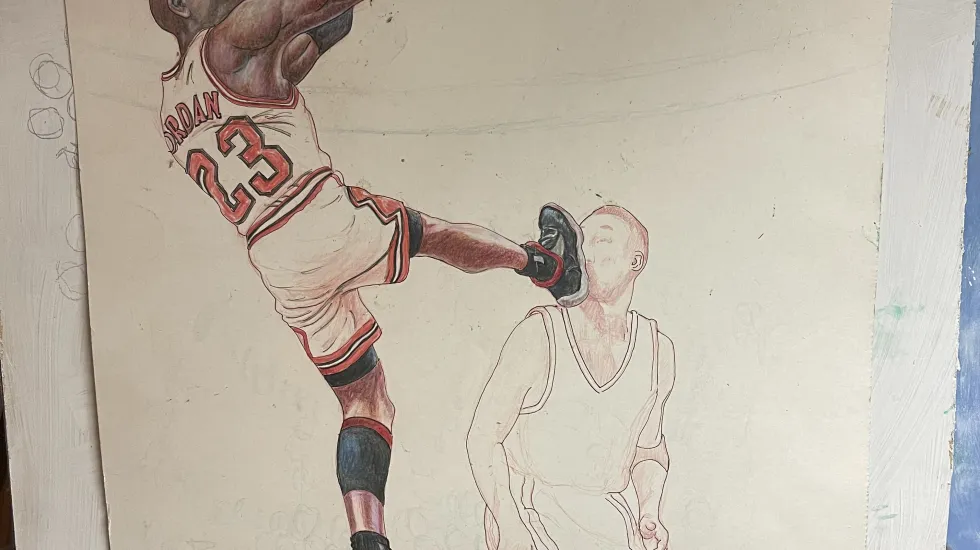

For young Sam, that meant being an artist.

“His easel was always set up in the back room,” said Mr. Nichols’ sister Marian Smothers, who acts under the name Marian Michaels.

At 9, he worked on a mule-drawn vegetable cart, running deliveries up and down the stairs of customers’ homes. At the end of each day, his boss “would give him a quarter and all the vegetables he could carry back to his mom,” his son said. He’d also sell scorecards and pencils outside Sox park.

During World War II, he worked as a busboy at the University of Chicago, where soldiers were fed “big pork chops,” his wife said. “They would give those who worked in the kitchen some of the food to take home.”

After Dunbar Vocational High School, he got a scholarship to the School of the Art Institute because he was “one of the finest artists,” Nichelle Nichols said in the oral history.

But he decided not to go.

“Finances at home were more important, meaning helping his parents,” according to his son.

Eventually, Mr. Nichols got an associate degree in art from Olive-Harvey College.

At the post office, Mr. Nichols created lobby displays to promote new stamps. When an Easter stamp was issued, he might craft big models of bunnies and eggs. For a circus stamp, he made clowns.

And always he painted.

“He fell in love with landscapes and seascapes because God created the heavens and Earth,” his son said. “He fell in love with the formation of rocks, stones, how trees grew and reached for the sun.”

“He was an incredible artist,” said Tyrone Haymore, executive director of the Robbins History Museum.

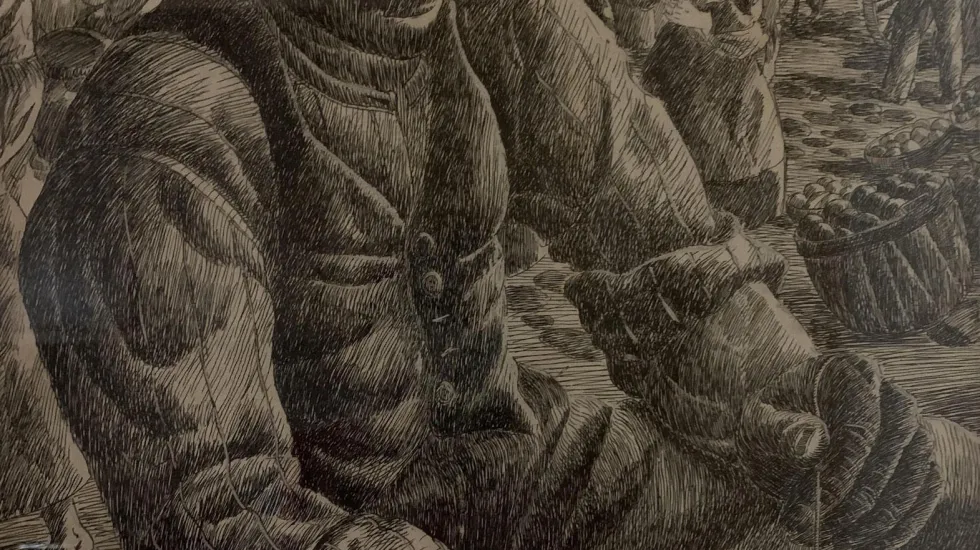

Kyle Johnson, the caretaker for his mother Nichelle Nichols, who has struggled with memory loss, owns a work by his uncle that depicts the mending of shoes in a medieval village.

“There’s just something about it that’s very warm and accessible,” he said.

At night, Mr. Nichols would sit outside, looking to the stars with binoculars and telescopes and telling his children: “God created that.”

He loved studying the night sky when he and his wife visited her hometown of Hazlehurst, Mississippi.

Mr. Nichols’ home was filled with hundreds of paintbrushes. He transported art supplies in his Oldsmobile Delta 88, which he prized for its smooth ride. He loved root beer, preferably A&W, drinking it straight or over ice cream.

Services have been held. In addition to his wife, son Franz and sisters Nichelle and Marian, Mr. Nichols is survived by his son Samuel E. Nichols III, sister Diane Robinson and five grandchildren. His brother Frank died before him, as did his brother Thomas, one of 39 people who died by suicide in 1997 at the California compound of the Heaven’s Gate cult.