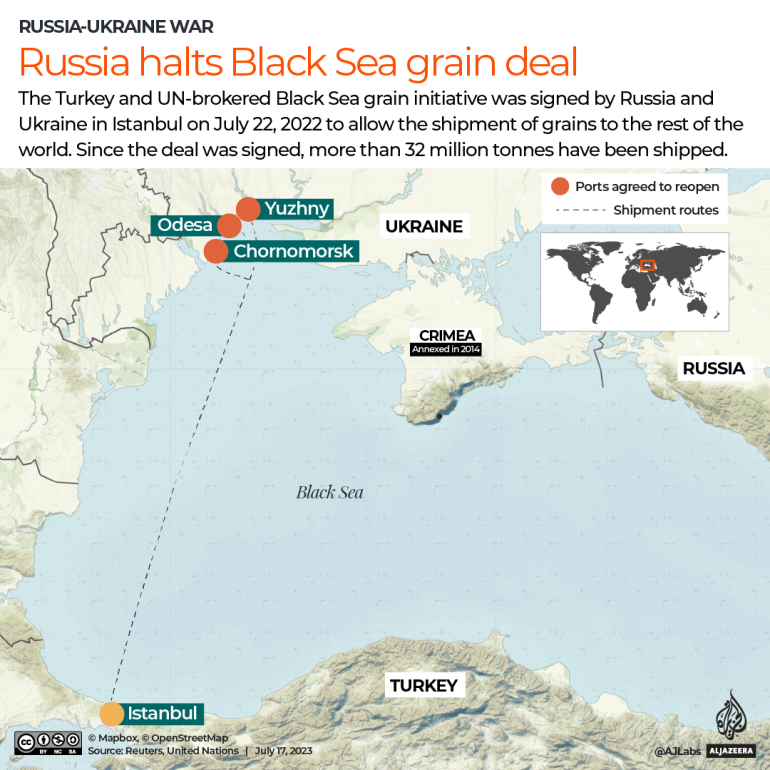

The Black Sea Grain Initiative – a deal brokered between Russia and Ukraine by the United Nations and Turkey – has allowed 32.9 million metric tonnes of food to be exported from war-torn Ukraine since August.

More than half of that grain went to developing countries, including those getting relief from the World Food Programme (WFP), according to the Joint Coordination Centre in Istanbul.

But the wartime accord, which had been extended several times, will be terminated on Tuesday, Russia announced on Monday.

Here’s a look at the deal and what it means for the world:

What’s the Black Sea grain deal?

The accord – signed by Russia’s Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu and Ukraine’s Infrastructure Minister Oleksandr Kubrakov in July last year at Istanbul’s lavish Dolmabahce Palace – created a safe corridor for Ukraine’s grain exports from three Ukrainian ports – Odesa, Yuzhny and Chornomorsk.

Under the agreement, a coalition of Turkish, Ukrainian and UN staff monitored the loading of grain into vessels in Ukrainian ports before navigating a preplanned route through the Black Sea, which is heavily mined by Ukrainian and Russian forces.

Ukrainian pilot vessels guided commercial vessels transporting the grain in order to navigate the mined areas around the coastline using a map of safe channels provided by the Ukrainian side.

The vessels then crossed the Black Sea towards Turkey’s Bosphorus Strait while being closely monitored by a joint coordination centre in Istanbul, containing representatives from the UN, Ukraine, Russia and Turkey.

Ships entering Ukraine were inspected under the supervision of the same joint coordination centre to ensure they were not carrying weapons.

What was the objective of the accord?

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24 led to a de facto blockade of the Black Sea, resulting in Ukraine’s exports dropping to one-sixth of their prewar level.

Kyiv and Moscow are among the largest exporters of grain in the world, and the blockade has caused grain prices to rise dramatically.

The deal aimed to help avert famine by injecting more wheat, sunflower oil, fertiliser and other products into world markets, including for humanitarian needs.

What has the initiative achieved?

The current deal has helped to bring down prices and ease a global food crisis.

Prices for wheat, the main ingredient in bread, have fallen about 17 percent so far this year while corn is down about 26 percent.

Ukrainian grain has played a direct role in easing a global food crisis with 725,200 tonnes, or 2.2 percent of the supplies, shipped through the corridor used by the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) as aid to countries such as Ethiopia, Somalia and Yemen.

The International Rescue Committee calls the grain deal a “lifeline for the 79 countries and 349 million people on the front line of food insecurity”.

However, as of Monday, almost 8 million tonnes of goods have been shipped to China, nearly 25 percent of the 32.9 million tonnes exported, according to the UN, while almost 44 percent of exports were shipped to high income countries.

Why did Russia terminate the deal?

Russia had been saying for months that conditions for the deal’s extension had not been fulfilled.

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin said last week that he wanted an end to sanctions on the Russian Agricultural Bank.

Other demands include the resumption of supplies of agricultural machinery and parts, lifting restrictions on insurance and reinsurance, the resumption of the Togliatti-Odesa ammonia pipeline and the unblocking of assets and the accounts of Russian companies involved in food and fertiliser exports.

“The Black Sea agreements ceased to be valid today,” Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov told reporters. “Unfortunately, the part of these Black Sea agreements concerning Russia has not been implemented so far, so [their] effect is terminated,” he added.

Can the Black Sea grain corridor operate without Russia?

Ukraine’s ports were blocked until the agreement was reached in July last year and it is unclear whether it would be possible to ship grain since Russia withdrew.

Additional war risk insurance premiums, which are charged when entering the Black Sea area, are expected to go up and shipowners could prove reluctant to allow their vessels to enter a war zone without Russia’s agreement.

War risk insurance policies need to be renewed every seven days for ships, costing thousands of dollars.

Can Ukraine export more grain through the EU?

Ukraine has been exporting substantial volumes of grain through eastern European Union countries since the conflict began. There have, however, been many logistical challenges, including different rail gauges.

Another issue is that the flow of Ukrainian grain through the eastern EU has caused unrest among farmers in the region who say it has undercut local supplies and been purchased by mills, leaving them without a market for their crops.

As a result, the EU has allowed five countries – Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia – to ban domestic sales of Ukrainian wheat, corn, rapeseed and sunflower seeds, while allowing transit for export elsewhere. As it stands, this will be phased out by mid-September.

Larger harvests are also expected in the eastern EU this summer and key ports, such as Constanta in Romania, are expected to struggle to handle the volume of grain they are likely to receive, leading to congestion and shipping delays.