Allegations have emerged recently that Ukrainian children are being forcibly removed from their country by Russia. Once there, they are put up for adoption.

These tactics are horrific, but far from rare. There is a long history of military aggressors forcibly transferring enemy children from their home countries as a means of sowing chaos and terror and weakening resistance.

In the U.S., the government conducted child abductions to quell the military resistance of America’s Indigenous peoples and prevent future opposition.

The Nazi practice of kidnapping “racially desirable children” from conquered countries and raising them as Germans has been well documented. And the communists’ abduction during the 1940s of nearly 28,000 Greek children to communist countries was also well known. The Greek delegation to the United Nations successfully pushed for the inclusion of child transfers within the legal definition of genocide specifically because of these abductions.

Child abductions are considered so heinous that the very first genocide convictions were of 14 Nazi officials charged with forcibly transferring Polish children to Germany. At trial, prosecutor Harold Neely suggested child abduction might even be the most outrageous of all the Nazis’ crimes. Neely said the world knew about mass killings and atrocities by Nazis, but he added, “the crime of kidnapping children, in many respects, transcends them all.”

In signing on to the genocide convention – an international treaty that criminalizes genocide – in 1948, the U.S. agreed that forcible child transfers constitute genocide. Yet it continued its own practice of Native child abductions for another 30 years.

Children as ‘hostages’

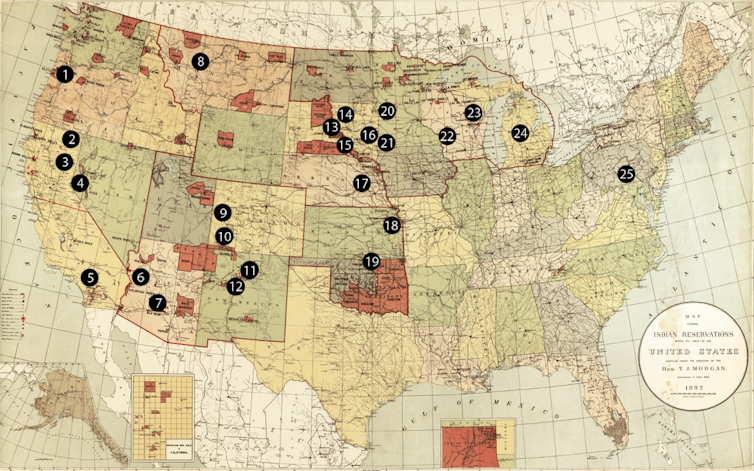

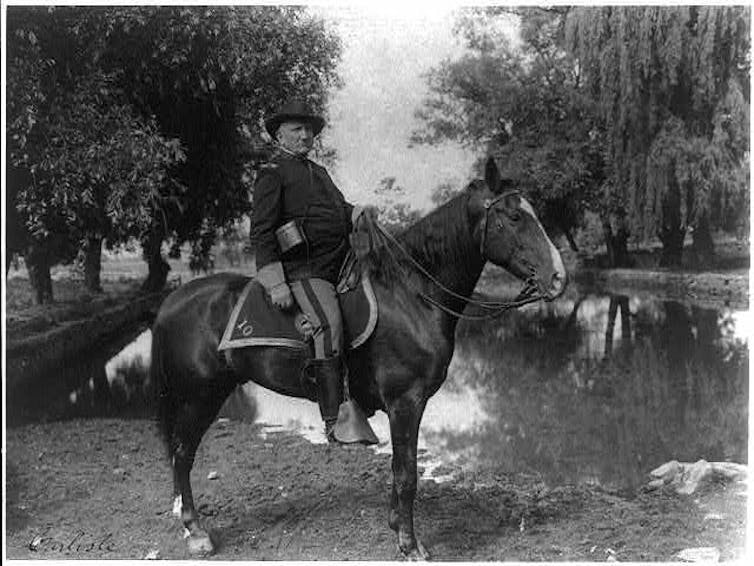

Beginning in the Colonial era, the American military kidnapped Native American children as part of a deliberate strategy to undermine tribal resistance and force native nations to agree to colonists’ demands.

Eleazer Wheelock, Dartmouth College’s founder, recruited students from local tribes because he recognized the tribes’ military importance. Wheelock referred to these children as “hostages.”

During the Revolutionary War, Congress appropriated US$500 to Dartmouth, ostensibly to educate Native American boys, but also because it believed their presence at Dartmouth would prevent the boys’ tribes from joining forces with the enemy British.

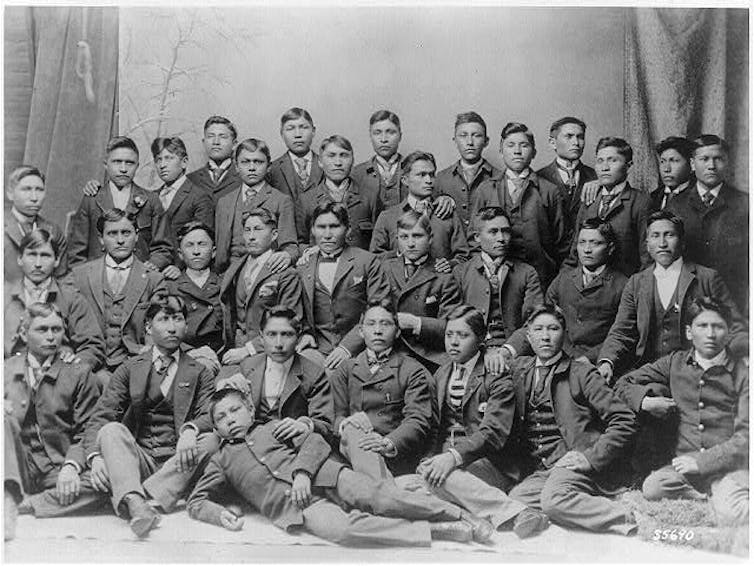

By the 19th century, the kidnapping of Native children from their families to send them to government-funded boarding schools was a widely practiced means of quelling Native resistance.

As Richard Henry Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, the first American Indian boarding school, explained in an 1878 federal report, one of the benefits of these institutions was the children could be used as “hostages for good behavior of [their] parents.”

‘Kill the Indian and save the man’

In these boarding schools, Native children were beaten, starved and sexually assaulted. A just-released report from the U.S. Department of the Interior acknowledges that children in these schools were forced to perform hard labor and were forbidden from speaking their Native languages or practicing their traditional religions or culture. According to the report, these schools “deployed systematic militarized and identity-alteration methodologies to attempt to assimilate American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children through education.”

Disease and death were also rampant. The federal report notes approximately 19 American Indian boarding schools “accounted for over 500 American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian child deaths. As the investigation continues, the Department expects the number of recorded deaths to increase.” Other sources estimate that as many as 40,000 children died at these schools.

Many American Indian parents fought desperately to keep their children. They were rarely successful. Some parents who refused to send their children to these schools had their government food rations withheld and faced starvation. Others were arrested.

If parents didn’t relinquish their children, government workers entered the reservations and captured the children, roping them like cattle.

In a 1932 hearing before the Congressional Committee on Indian Affairs, one Native American father testified, “I had a boy going to school that took sick and brought him home, after five days at home he died.”

Eventually, a 1928 study known as the Merriam Report, done at the behest of the U.S. Interior secretary, and a 1969 Senate report titled “Indian Education: A National Tragedy – A National Challenge” exposed the horrors of the Indian boarding schools, and the government ordered them closed.

But the removal of Native American children by state and federal agencies continued through adoption policies that forced these children into non-Native adoptive homes. Like boarding schools which, as Pratt stated, sought to “kill the Indian and save the man,” the goal of 20th-century American Indian child adoptions was to save Native children through assimilation and the destruction of tribal culture.

“The aim,” said Sandra White Hawk, founder of the First Nations Repatriation Institute, “was assimilation and extinction of the tribes as entities, as their younger generations were removed, year after year – just as it had been with the boarding schools.

Emotional and psychological scars

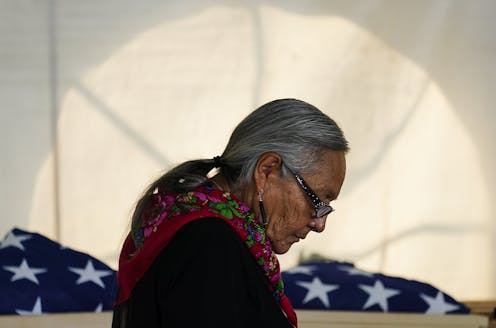

The harm caused by the United States’ Native American child removal policies was staggering. Removed children bore severe psychological and emotional scars that many passed on to their children and their children’s children.

Generations of American Indian children lost the ability to speak their Native language, practice their traditions and pass on their culture. These losses threatened the very existence of tribes.

As Calvin Isaac, tribal chief of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, explained to Congress in 1978, "Culturally, the chances of Indian survival are significantly reduced if our children, the only real means for the transmission of tribal heritage, are to be raised in non-Indian homes and denied exposure to the ways of their people.”

In response to the testimony of Chief Isaac and other American Indian advocates, Congress passed the 1978 Indian Child Welfare Act.

The Indian Child Welfare Act acknowledged the harm of these removals and sought to address their devastating and continuing repercussions. This policy is controversial. The act is opposed by those wishing to adopt American Indian children and those who believe the act’s preference for tribal placements is racist.

Currently, the Indian Child Welfare Act is being challenged in the Supreme Court. The case, Brackeen v. Haaland, to be argued in fall 2022, concerns the potential adoption of a Navajo child by a non-Native couple. Under the Indian Child Welfare Act, such adoptions may only occur if there is no extended family member, tribal member or “other Indian family” available to adopt the child.

This provision was enacted to keep Native children connected to their families and culture and to reverse the devastation caused by the centurieslong child removal policies. At trial, the Brackeen plaintiffs argued that this preference for tribal and other Indian placements over non-Native placements is unconstitutional race discrimination. They won. Now, the case is before the Supreme Court and, although the court has previously upheld the constitutionality of the act, the outcome of Brackeen is unclear.

In enacting the Indian Child Welfare Act, Congress recognized that only a comprehensive and detailed federal statute could possibly reverse the horrific legacy of Indian child abductions.

The Brackeen case challenges Congress’ ability to protect tribes and their citizens through the passage of laws like the Indian Child Welfare Act. The decadeslong fight over the act highlights the long-term devastation of forced child transfers, as well as the extreme difficulty of remedying these effects.

If Russia is forcibly adopting Ukrainian children, then, as U.S. history painfully demonstrates, the trauma of these abductions may span generations.

Marcia Zug ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.